Cerebral venous sinus thrombosis (CVST) is a rare type of stroke caused by a clot forming in one of the intracranial sinuses and subsequent blockage in blood drainage. Even though venous thromboembolism affects 0.1% of the population, CVST is a rare disease that occurs in 5 people per 1 million, annually and is responsible for 0.5% of all strokes (Ferro, 2007; Devasagayam et al, 2016; Heit et al, 2016; Luo et al, 2018; Johns Hopkins Medicine, 2020). The disease may be observed at any age, but is most likely to be diagnosed among young people, especially women (Alvis-Miranda, 2013). Though it is a relatively rare disease in the general population, it is one of the most common cerebrovascular complications in pregnancy, affecting 1.6 out of 100 000 deliveries (Saposnik et al, 2007). Like any other thrombotic process, the CVST is well explained by the traditional Virchow triad (hypercoagulability, vessel wall damage, and blood stasis) (Kumar, et al, 2018).

The manifestation of CVST can take various forms, which may lead to irregularities in its clinical diagnosis. Neurological focal symptoms, sudden-onset headache, disturbances of consciousness, and seizures are the most common clinical features. The condition is fatal for approximately 4.3% of cases (Ruiz-Sandoval et al, 2012; Boucelma, 2013). A variety of risk factors can be identified in 70-80% of patients (Ehler, 2010). These include middle ear inflammation, facial skin infections, pregnancy and the postpartum period, oral contraception, surgery, head and neck injuries, tumours, lumbar puncture or hypercoagulable states (Leiden V gene mutation, antiphospholipid syndrome, deficiency of antithrombin III, C and S proteins, inherited or de novo mutations) (de Freitas and Bogousslavsky, 2008; Ehler, 2010; Alvis-Miranda et al, 2013). It is worth emphasising that caesarean section increases risk of thromboembolism (Ehler, 2010). Table 1 sums up all predisposing factors of CVST.

Table 1. Risk factors for cerebral venous sinus thrombosis

| Acquired | Inherited |

|---|---|

| Pregnancy and postpartum | Deficiency of antithrombin III |

| Surgeries (including caesarean section) | Deficiency of C and S proteins |

| Oral contraception and hormonal replacement therapy | Leiden V gene mutation |

| Tumours | Lupus anticoagulant |

| Head and neck injuries | Prothrombin gene mutations |

| Neurological disorders | Anticardiolipin antibodies |

| Inflammatory diseases (including middle ear inflammation and facial skin infections) | Hyperhomocysteinemia |

| Lumbar puncture |

Adapted from Al-Sulaiman et al, 2019

Case report

The patient was a 33-year-old woman, gravida 3, para 2, admitted to the Perinatology Clinic of Jagiellonian University in Kraków at 39+5 weeks of gestation. The reason for admission was a caesarean section planned because of a history of caesarean section during a previous pregnancy in 2013. On admission, there were no abnormalities, except for rhinitis and sore throat treated with azithromycin that had been previously prescribed by the patient's GP. The patient had experienced one miscarriage in the past, but the cause remained unknown. Apart from this, her past medical history was not significant. There were no abnormalities on physical examination. After one day of hospitalisation, the woman was prepared for a caesarean section under spinal anaesthesia. A healthy baby boy was delivered with Apgars of 10 at 1 minute and 10 at 5 minutes. Five minutes after delivery of the fetus, the patient complained of shortness of breath. She then developed signs of high spinal anesthesia (severe dyspnea, saturation: 94%). As a result of the imminence of acute respiratory insufficiency, the patient was intubated and subsequently transferred to the intensive care unit. After a few hours of synchronised intermittent mandatory ventilation mode mechanical ventilation, the patient was extubated and transferred to the maternity ward the following day, from where she was discharged after 3 days. A total of 72 hours after discharge, the patient was referred back to the hospital by her GP. Physical examination and laboratory findings upon readmission revealed elevated levels of D-dimers with accompanying headache, back pain, and tingling sensation in the right thigh.

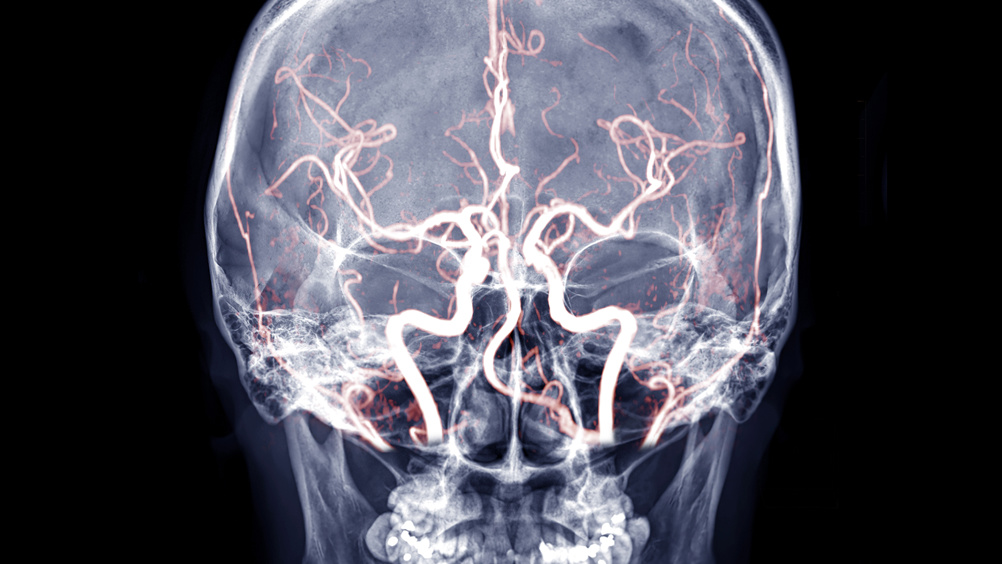

A performed computer tomography scan revealed increased contrast signal around the perimeter of the distal section of the internal jugular vein and decreased contrast in both left transverse and sigmoid sinus. Both of these findings confirmed the presence of thromboembolic material in the mentioned cavities. Based on the patient's overall state and performed examination, the definitive diagnosis was CVST. Blood clots were located in the left transverse, sigmoid sinuses, and the left internal jugular vein. The patient was transferred to the Neurology Clinic of Jagiellonian University in Kraków, where alexia, aphasia, and cerebral venous infarction of temporal and parietal lobes were diagnosed.

Subsequent magnetic resonance imaging showed an absence of flow signal in the mentioned vessels and thrombi elements in both confluence of sinuses and superior sagittal sinus. The left hemisphere's image was significant of a lesion sized 35x28x40 mm, located on the temporal-parietal-occipital area. The lesion was characterised as a hemorrhagic venous infarction; it was partially filled with hemolysed blood, with visible oedema, accompanied by a compression of the left lateral ventricle. A second similar lesion with signs of oedema was found in the left cerebellar hemisphere. The patient was successfully treated with unfractionated heparin, low-molecular-weight heparin, warfarin and painkillers, then discharged home in good condition, with no focal signs and mild dyslexia. Thyroid hormone concentration, immunological tests for systemic diseases, blood and urine cultures, throat and nose swabs results were normal. Otorhinolaryngological, dental and cardiological examinations (including echocardiography examination of the heart) revealed no abnormalities. During an additional 4 years of observation, no coagulation defects were detected.

Discussion

CVST is a severe disease that can result in long-term neurological deficiency. Higher incidence among pregnant women is a well-documented phenomenon (Soydinc et al, 2013; Dhadke, 2020). Physiological changes associated with pregnancy, such as the increased risk of blood clots, oedema, increased weight, or altered habits, such as the reduced amount of physical movement, facilitate the occurrence of unfavourable changes in the cardiovascular system (Bręborowicz, 2016). Diagnosis of CVST can be difficult because of its multifactorial nature and the presence of various manifestations. It poses a particular challenge, especially in patients with nonspecific symptoms, such as mild headaches and minimal or absent neurological deficits. Nonetheless, almost 90% of diagnosed patients complain of a headache and present with focal lobar syndrome, seizures and encephalopathy (Al-Sulaiman et al, 2019). Based on the literature, CVST is an essential diagnostic consideration in patients with all types of headaches (Boucelma, 2013). Both computed tomography and magnetic resonance imaging should be used in all ambiguous clinical situations. These techniques are essential in increasing the rate of CVST diagnosis in patients with nonspecific presentations (Al-Sulaiman et al, 2019.) As a potential group at risk, all postpartum women should be carefully screened for the potential development of CVST symptoms. Based on the guidelines, treatment of CVST in pregnant women should primarily include low-molecular-weight heparin (Ferro, 2017). The diagnosis, as well as appropriate treatment, should be a result of close cooperation between the obstetricians and neurologists.