In pregnancy and 6 weeks postnatally, the risk of maternal mortality in the UK is significantly higher for women who are not of white ethnicity (Knight et al, 2018). Women from ethnic minorities express dissatisfaction with maternity care, stereotyping, racism, language barriers and unmet expectations (Henderson et al, 2013; Jomeen and Redshaw, 2013; Higginbottom et al, 2019; Bawadi et al, 2020). Public Health England (PHE, 2019) recognises health inequalities as a major concern and is attempting to reduce them (NHS, 2020). Midwives are tasked with providing individualised care to women (Nursing Midwifery Council (NMC), 2019) and are encouraged to develop awareness of inequalities using self-reflection to recognise where their personal delivery of care may disadvantage non-white British women (Knight et al, 2019). When considering inequalities within their practice, midwives may focus their efforts on tackling issues they perceive to be key contributing factors. Hence, it is important to understand what midwives perceive are contributing factors to health inequalities for non-white British women.

Terms such as ‘black, Asian and minority ethnic’, ‘black and minority ethnic’ or ‘ethnic minorities’ are often used to describe groups of people who are not white or British; these terms are avoided in this review. British political, social and healthcare structures are designed around white, westernised British culture and, therefore, white British culture is familiar within the NHS. Midwives will encounter women who have unfamiliar histories, traditions, religions or cultures and the term non-white British reflects the difference of familiarity.

Methods

A literature search was conducted on electronic databases (MEDLINE complete, CINAHL, Science Direct, Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews and Scopus) in January 2021; further papers were found from handsearching references in papers and an internet search for grey literature targeting organisations such as the National Perinatal Epidemiology Unit (2020) and the National Institute for Health Research (2020). A handsearch of citations and a cited reference search in Scopus was used to find additional papers. The SPIDER tool (Cooke et al, 2012) guided the search using Boolean operators and filters (Table 1).

Table 1. SPIDER tool for literature search

| Sample | UK midwives | (Midwi* OR health care professional OR maternity) AND (United Kingdom OR UK OR Britain OR Wales OR NHS) and equivalent terms |

| Phenomenon of interest | Contributing factors to ethnic disparity in maternity | (ethnic minorit* OR Black) AND (maternity OR pregna*) AND (inequalit* OR discriminat*) and equivalent terms |

| Design | Interviews, observational studies, contemporaneous | Interviews or observations |

| Evaluation | Perceived barriers to delivering appropriate care to women of ethnic minorities | (attitude* OR view*) and equivalent terms |

| Research type | Qualitative data | Qualitative research methods |

Duplicates were removed and articles screened by title to exclude irrelevant studies. Abstracts were included or excluded based on the inclusion criteria (Table 2).

Table 2. Inclusion and exclusion criteria

| Inclusion | Exclusion | Rationale |

|---|---|---|

| Site of research within the UK | European or global studies where results for UK are not distinguishable from other countries | Maternal and perinatal morbidity and mortality varies by country (World Health Organization, 2020). The aim of this review was to address the disparity in the UK (Knight et al, 2019) and therefore only UK-based studies were included |

| Views/experiences of midwives central to the study | Views/experiences of women only | The review aims to recognise midwives as stakeholders in maternity care provision and lead practitioners in perinatal care (Nursing and Midwifery Council, 2019) therefore studies were excluded where the views of midwives were not discernible from other professionals or women |

| Midwives practicing in the UK at time of study | Healthcare focus where maternity care is not the main aim of the research | |

| Midwifery practice where care planning is essential eg early pregnancy, antenatal, postnatal | Studies focus is specific to one area eg breastfeeding, mental health, high risk, caesarean sections | Inequalities among women from different ethnicities is a broad issue, therefore only studies that engage with essential care are included. Some women will access minimal maternity care and therefore more focused studies are excluded |

| 2010–2020 | Before 2010 | The review aims to observe contemporaneous trends as these contribute to the findings of the MBRRACE UK report (Knight et al, 2019) |

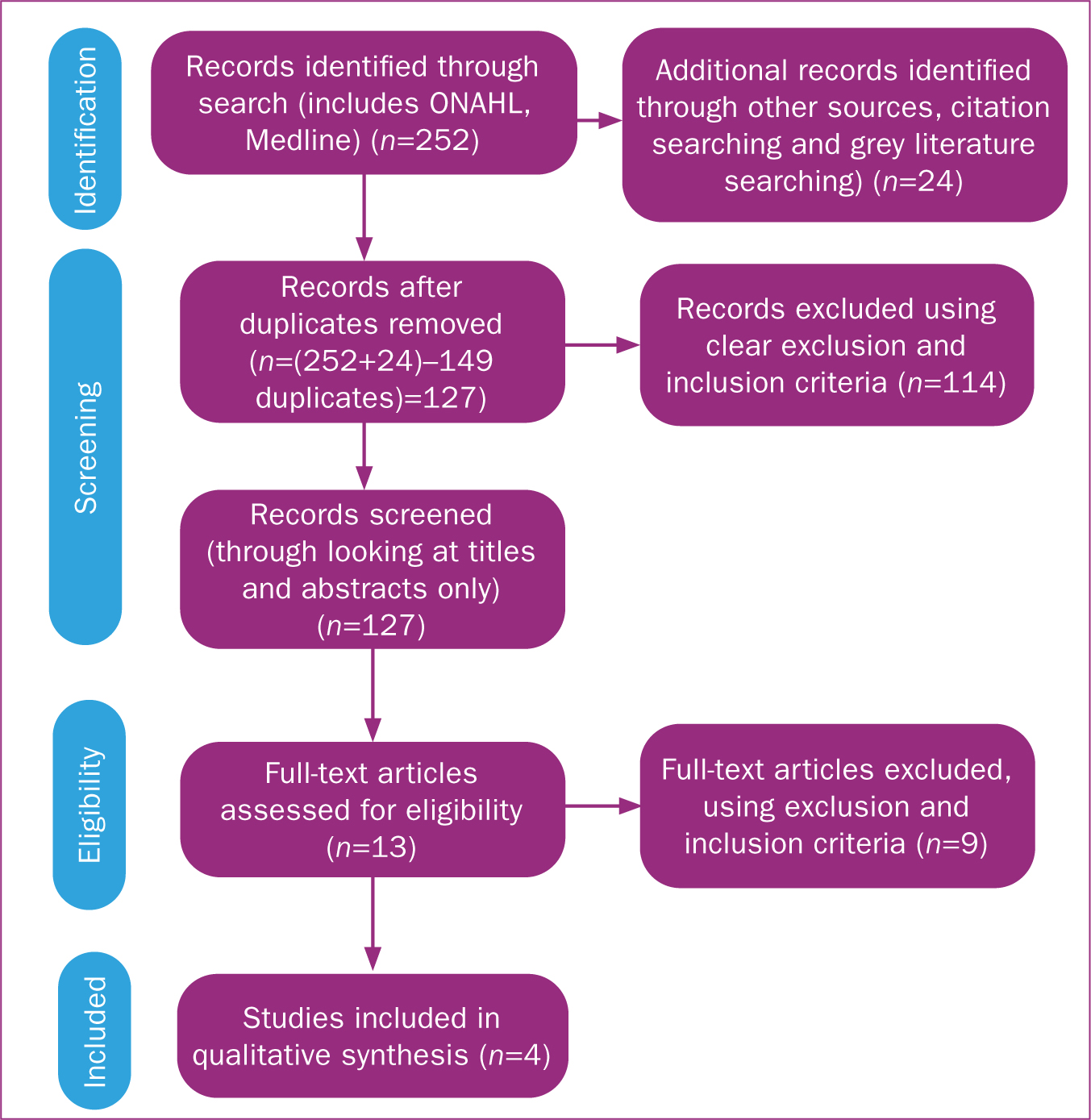

The final studies were read in full and appraised. The Critical Appraisal Skills Programme (2018) tool was used to assess the quality of the studies. The Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) (Moher et al, 2009) was used to accurately document the search results (Figure 1).

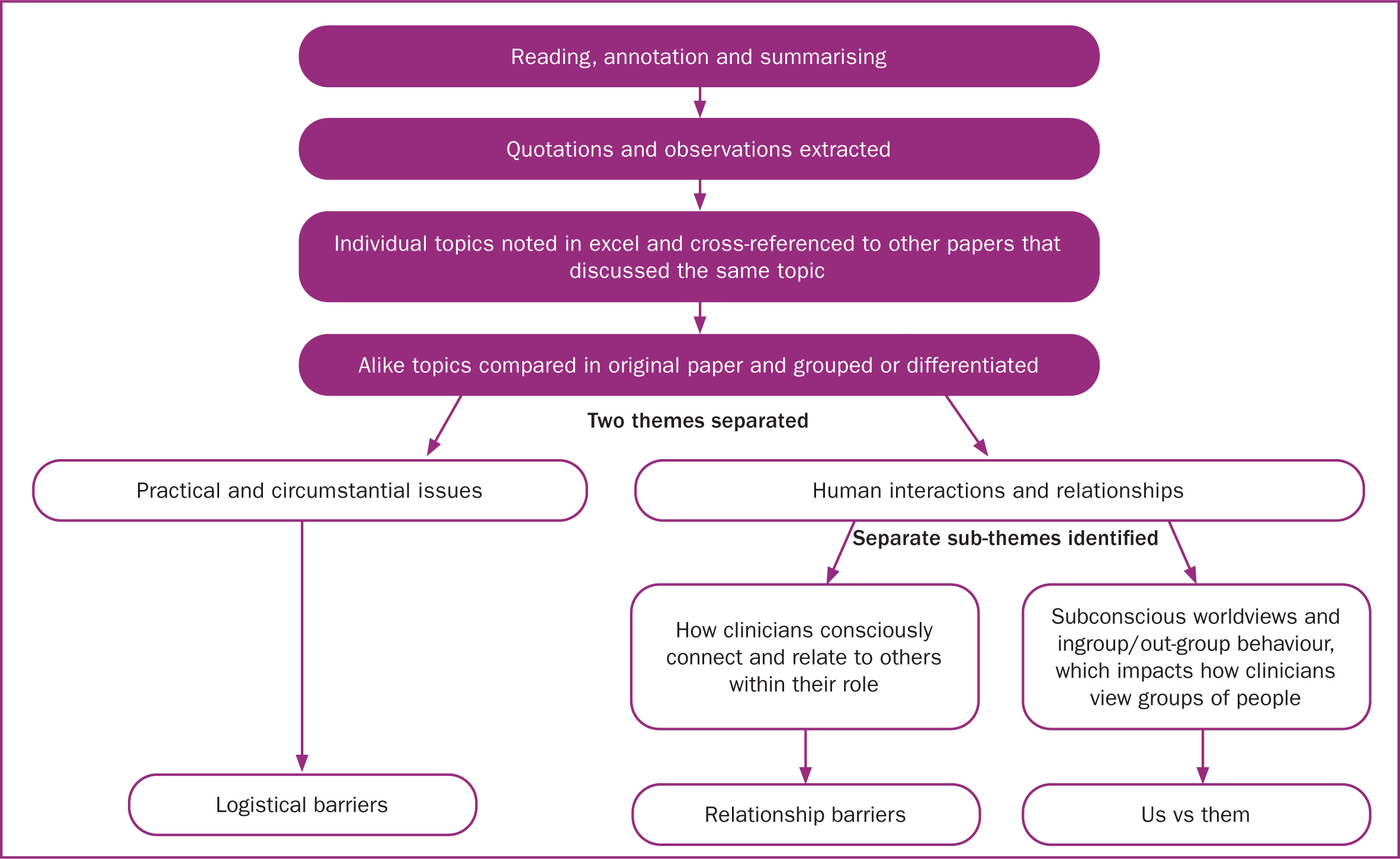

Quotations of clinicians and observations were highlighted and extracted onto a document. The articles were then re-read with each topic discussed typed into excel and cross-referenced to other papers that discussed the same topic. These topics were grouped into concepts, combining topics that were alike. Excel was used to record themes from each paper to enable comparisons to be made and broader topics to be drawn out.

When looking at the words quoted by midwives in the papers, the focus was on cultural, logistical and practical factors that contribute to health inequalities. However, these are superficial themes and analysis of the full communication of midwives was completed (Figure 2). The themes were discussed with a research supervisor to minimise researcher bias. The quotes of the clinicians and observations by the researchers were tracked back to through the analysis in order to ensure the participants' experiences were reflected accurately in the review.

Results

In total, 276 papers were found and screened for eligibility and four studies were included (Table 3).

Table 3. Summary of included studies

| Richards et al (2014) | Aquino et al (2015) | Goodwin et al (2018) | Hassan et al (2020) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Type of research | Qualitative: no specified method. Bradford | Qualitative: no specified method. Greater Manchester | Qualitative: ethnography. South Wales | Qualitative: no specific method. Northwest England |

| Professional expertise of researchers | Public Health (University of Leeds and Bradford Metropolitan District Council) | Psychological Sciences and Health Sciences (City University London, University of Manchester and Manchester Unit for Health Psychology) | Health Sciences (University of Birmingham and University of Cardiff) | Health Sciences, Midwifery and Maternal and Child Health (University of Liverpool, John Moores University Liverpool and University of Bedfordshire) |

| Aim | To investigate health status and influencing factors of health of Eastern European mothers and infants | To understand barriers midwives face when trying to provide equitable care to black and minority ethnic women, and midwives' perceived role in tackling inequity in maternity care | To explore relationship between first generation Pakistani women and midwives, what contributes to quality of relationships and how they might affect care given | To explore healthcare professionals' experience providing maternity care for Muslim women |

| Methods | Semi-structured interviews with healthcare professionals and support volunteers. Recruited by purposeful sampling. Topic guide derived from evidence from literature review. Thematic analysis used with deductive approach to development of themes | Semi-structured interviews. Topics: professional experience of providing care for black and minority ethnic women, views of health inequalities and midwifery training. Thematic analysis. Constant comparison technique used for consistency | Field work, review of media observations and interviews. Purposeful sampling of participants then snowballing. Thematic analysis and inductive approach to development of themes. NVivo 10 software. Data gathered and analysed concurrently with input from support group | Semi-structured interviews with maternity staff. Snowballing sampling. Topic guide (available) derived from data collected from first two phases of research. Thematic analysis with Word and Excel |

| Ethics and reliability | No ethical approval noted. Pilot study conducted, coding process repeated for reliability. Acknowledged no conflict of interest. Saturation reached | Ethical approval from participating NHS Trust and University of Manchester. Detailed description of recruitment and consent process. Acknowledged no conflict of interest. Documented potential bias of researchers and strategies to overcome this. Pilot study conducted and independent analysis | Ethical approval from NHS Research Ethics Committee and reviewed by University of Cardiff. One declaration of interest in Royal College of Midwives: partial funding for B Hunter. Thorough explanation of method of ethnography and strategies to avoid bias, including support group to advise with members from outside organisations. Saturation reached | Ethical approval from NHS Research Ethics Committee. Recruitment from existing relationship within trust because of previous research. Detailed description of recruitment and consent. Acknowledged no conflict of interest |

| Number and role of participants | 11 participants: 2 volunteers, 4 health visitors, 5 community midwives | 20 midwives from variety of clinical areas | Observations: 7 midwives (2 were interviewed), 15 women (6 Pakistani women, 2 were interviewed).Interviews: 11 midwives, 9 Pakistani participants: 7 women, 1 interpreter, 1 mother of participant | 12 participants: 7 midwives, 1 sonographer, 2 gynaecology nurses, 2 breastfeeding support workers |

| Themes | 1. Health: i) Wider determinants, ii) General behaviours, iii) Maternal and infant. 2. Cultural barriers: i) Mobility, ii) Language and communication, iii) Maternal age and family size, iv) Abuse and neglect. 3. Access to services: i) Difficulties with engagement, ii) Relationship, iii) Challenges | 1. Language. 2. Expectations of maternity care. 3. Complex needs extending beyond maternity care | 1. Family relationships 2. Culture and religion 3. Understanding different healthcare systems | 1. Healthcare professionals' perceptions about Muslim women. 2. Healthcare professionals' understanding and awareness of religious practices. 3. Healthcare professionals' approaches in addressing and supporting women's religious needs. 4. Importance of training in providing culturally and religiously appropriate women-centred care |

| Other linked studies | Builds on previous research from Bowler (1993), an ethnographical study in same area of country Third part of three phase study (Hassan, 2017; Hassan et al, 2019) |

Richards et al (2014) published a study on Eastern European women in Bradford. A total of 11 participants, midwives, health visitors and volunteers discussed their perceptions of the factors that influence health outcomes for women and their babies. Although the paper itself is qualitative, the researchers highlight the difficulty of obtaining any quantitative data for Eastern European women to support their background reading, and statistically acknowledge the health barriers for this group. They also acknowledge a lack of research into women's views. For this reason, the study does not manage its aim, as it only shows the perspectives of the professionals; however, it is relevant to this review because of this focus. No ethical approval was documented. Thematic analysis identified three key themes: health, cultural barriers and access to services. Within health, the subthemes were living conditions, socioeconomic factors and health lifestyle behaviours. Within cultural barriers, subthemes were communication, trafficking, social roles and stereotypes. Within access to services, subthemes were poor engagement, trust and expectations.

Aquino et al (2015) interviewed 20 midwives in Greater Manchester on the professional experience of providing care for black and minority ethnic women, views of health inequalities and midwifery training. Sampling was heterogenous across areas of practice and stages of career to encompass a range of perspectives. Thematic analysis identified three key themes: language, expectations and complex needs. The study highlighted the concern of midwives wanting to provide equitable care but there being multiple barriers that prevented this.

Goodwin et al (2018) used ethnography in their study on the relationship between midwives and migrant Pakistani women in Wales. Fieldwork, reviews of media sources, observations and interviews explored the interactions of the two cultures, resulting in three themes, the impact of family relationships, culture and religion and navigating the NHS. The study highlights consistency between women and midwives with regard to the perceived issues in maternity care; however, on a deeper level, there is a disconnected understanding of these issues between the two parties.

Hassan et al (2020) published a three-phase qualitative study in Greater Manchester on professionals' experiences of providing maternity care for Muslim women. A total of 12 participants, the majority of whom were midwives, were recruited. Semi-structured interviews used a topic guide and were thematically analysed resulting in four key themes: healthcare professionals' perceptions about Muslim women, understanding and awareness of Islamic practices, approaches to supporting Muslim women's religious needs and training of culturally and religiously appropriate care. Language was a theme that also appeared in the responses, although the study itself did not specifically ask about migrant or non-English speaking women – this was an assumption made by the participants (personal communication Dr S Hassan, October 2020). The study highlighted a serious lack of quality cultural competency training.

Quality of included studies

On assessing the quality of the studies, Aquino et al (2015), Goodwin et al (2018) and Hassan et al (2020) were of higher quality than Richards et al (2014); therefore, more weight was attributed to these papers (Table 4). Richards et al (2014) was assessed as poorer quality because of the lack of ethical approval documented and because the aim of the research was not met by the study.

Table 4. Strengths and limitations of included studies

| Paper | Strengths | Limitations |

|---|---|---|

| Richards et al (2014) | Clear research aim. Appropriate design and methodology. Appropriate recruitment of professionals. Field notes. Saturation reached | Lack of data coding for A8 countries means less background research to use. Method not appropriate to fulfil aim as only taking professionals' views. No ethical approval documented. No discussion of compounding stereotypes that may cause bias in the data. Not clear from paper if coding was checked by second author, just that codes from pilot were second checked. Paper does not recognise that to ensure balance, women's views need to be voiced in a similar study |

| Aquino et al (2015) | Clear research aim. Appropriate design and methodology. Ethical approval. Independent analysis of transcripts. Independent coding with collaborative consensus. Demonstration of effort to reduce researcher bias. Practical recommendations | One NHS Trust in Manchester with diverse population; therefore, not transferable to rural or less diverse context. No mention of saturation of data |

| Goodwin et al (2018) | Clear research aim. Appropriate design and methodology. Ethical approval. Reproduction of previous research. Project team not just academic. Significant hours of field notes and observations. Saturation reached | No examination of bias by researcher but data examined by group that included consultant midwife and member of race equality first |

| Hassan et al (2020) | Clear research aim. Appropriate design and methodology. Full interview guide available. Ethical approval. Extensive three-part project. Saturation reached. Acknowledgement of ethnicity of healthcare professional. Specific training needs identified | One NHS Trust in northwest of England with diverse population; therefore, not transferable to a rural or less diverse context. No blanket approach to sampling so some potential participants could have been missed |

This analysis revealed three underpinning themes: ‘relationship barriers’, ‘logistical barriers’ and ‘us vs them’ (Table 5). Midwives did not mention racism directly; however, the impact of implicit bias, stereotypes and structural racism are evident, therefore racism was included in the discussion.

Table 5. Emerging themes

| Themes | Hassan et al (2020) | Goodwin et al (2018) | Aquito et al (2015) | Richards et al (2014) | Relationship barriers | Logistical barriers | Us vs them | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Practical issues | Communication (two papers address theme) | X | X | X | X | X | ||

| Complex needs - housing/health/welfare/immigration (two papers address theme) | X | X | X | X | ||||

| Language (four papers address theme) | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | |

| Cultural issues | Concerns re safety of cultural or religious practices or advice from family members (three papers address theme) | X | X | X | X | X | X | |

| Expectations of services (four papers address theme) | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | |

| Family members too involved (three papers address theme) | X | X | X | X | X | |||

| Midwives assumptions seen as problematic (three papers address theme) | X | X | X | X | X | |||

| Women disempowered in the culture (three papers address theme) | X | X | X | X | X | |||

| Logistical issues | Poor engagement with services (three papers address theme) | X | X | X | X | X | X | |

| Shortages of staff or resources (two papers address theme) | X | X | X | X | ||||

| Training (three papers address theme) | X | X | X | X | ||||

| Other | Legal and professional accountability (two papers address theme) | X | X | X | X | |||

| Racism – awareness of own institutional bias | X | X |

Discussion

Midwives aimed to give woman-centred care and showed commitment to this responsibility (Aquino et al, 2015; Hassan et al, 2020). However, midwives communicated multiple barriers that contribute to inequalities in the care received by women.

Logistical barriers

Practical obstacles for midwives to deliver equitable care were discussed in each paper. In particular, language and interpreters, the complexity of social and health needs and poor engagement with services. Midwives cited their commitment to giving good quality, equitable care, even in under-resourced environments (Aquino et al, 2015).

Relationship barriers

The midwife–woman relationship was held in high regard by midwives in all papers. Midwives disclosed concerns when the relationship was difficult to build as a result of mobility or language, especially with regards to safeguarding (Richards et al, 2014).

Us vs them

An ‘us vs them’ attitude was strongly prevalent in all papers. This theme was evident in the midwives' quotes in the papers and the assumptions the midwives made such as stereotyping male headship in the household (Goodwin et al, 2018) or generalising one religious group as having language barriers (Hassan et al, 2020).

There are publications that discuss the role of relationship and logistical barriers in UK maternity care, but there appeared to be less focus on attitudes and perceptions of clinicians, as shown in the us vs them theme. This review focuses on three areas within this theme: ‘incongruent expectations’, ‘structural racism, stereotypes and implicit bias’ and ‘culture vs professional accountability’.

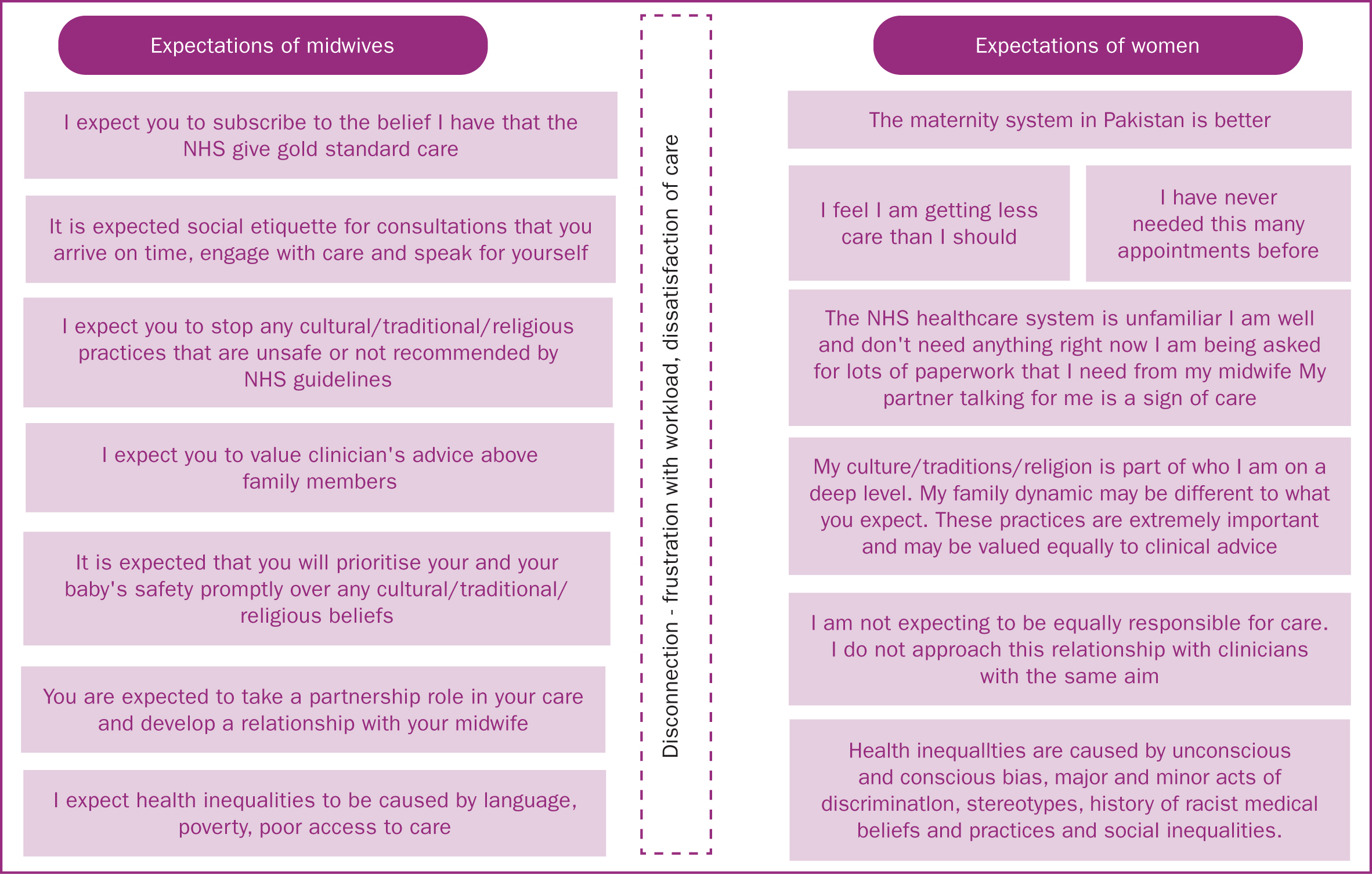

Incongruent expectations

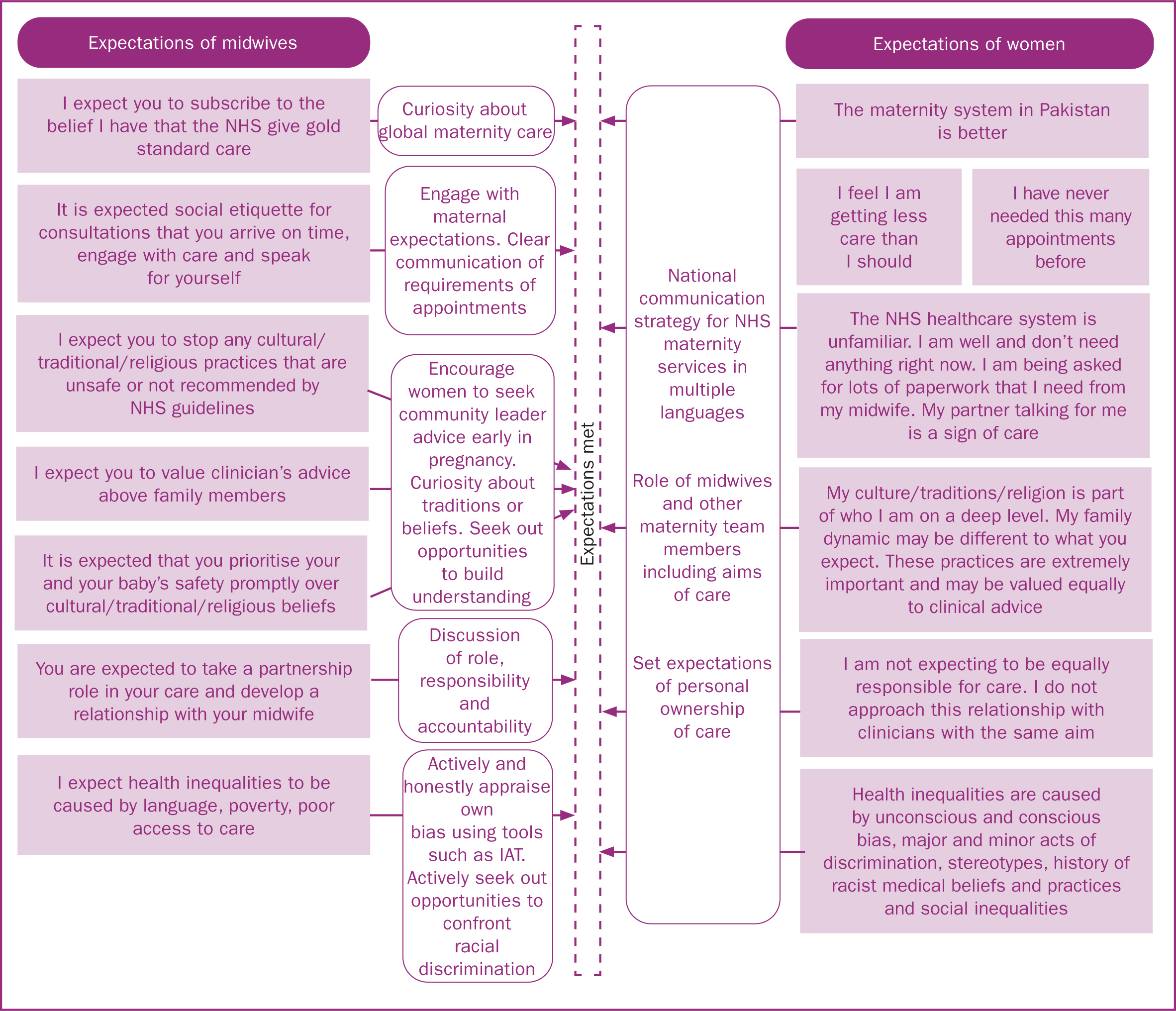

Recent publications discuss the role of expectations in maternity care (Department of Health, 2010) and specify the mutual responsibility of midwives and women in care (National Maternity Review, 2016). The data from this review showed that the expectations of midwives and non-white British women could be very different (Figure 2) and midwives believed that this was a significant factor in health inequalities and dissatisfaction with care (Goodwin et al, 2018).

Midwives perceived that women's expectations of maternity care were based on the care typically offered in their country of origin (Aquino et al, 2015) and assumed the NHS gives superior care, a view that was reported not to be shared by women (Goodwin et al, 2018). Some midwives believed that women do not value their time and expertise (Richards et al, 2014; Goodwin et al, 2018), describing frustrations with women who do not meet their expectations of time keeping, social etiquette for consultations and engagement with services. Women and some midwives attributed this to poor navigation of the NHS and logistical barriers (Aquino et al, 2015; Goodwin et al, 2018). The papers in this review recommended that this could be addressed by engaging with expectations (Goodwin et al, 2018) early in pregnancy (Aquino et al, 2015), in women's own language (Richards et al, 2014) and improved cultural competency training (Hassan et al, 2020) (Figure 4).

Structural racism, stereotypes and implicit bias

Although a wealth of evidence shows that minor acts of discrimination and unconscious bias cause health inequalities (Drewniak et al, 2017; Fitzgerald and Hurst, 2017; Williams et al, 2019), this contributing factor was barely mentioned by midwives and was only discussed by Hassan et al (2020) and Aquino et al (2015).

Structural racism

Midwives perceived multiple structural barriers faced by non-white British women; interpreters, extra allocated time and specialised services were all acknowledged and appreciated as supportive factors to reducing health inequalities (Aquino et al, 2015; Richards et al, 2015; Hassan et al, 2020). However, the commissioning of finance to NHS trusts through care pathways is currently not able to capture the nuance of personalised care, such as extra time for discussion of cultural needs (NHS Improvement, 2020). This could lead to further health inequalities. The Joint Committee on Human Rights (2020) acknowledges the lack of targeted financial support. Unless structural racism is addressed in a deliberate financial strategy to reduce inequalities, midwives will be unable to utilise resources to meet individual needs.

Stereotypes

Women were reported to be subjected to stereotyping from staff in all four papers. Negative stereotypes were created and held even without evidence or personal experience (Goodwin et al, 2018). The stereotypes identified in all four studies showed an assumption that non-white British women were unconcerned about their own health, indifferent to time-keeping pressures of professionals, disempowered by men, unlikely to make wise clinical choices, demanding of administrative tasks for access to government support and had limited or extensive support networks. For example, it was assumed that Eastern European women lacked social support (Richards et al, 2014) and Muslim women had extensive family support networks to draw on (Hassan et al, 2020). This presumption could contribute to poor clinical support being given based on stereotypes, leading to the dissatisfaction of care discussed by Aquino et al (2015) and Goodwin et al (2018), as well as a discordant relationship with the NHS (Richards et al, 2014).

Implicit bias

Self-awareness of one's own implicit bias can in itself reduce that bias (White et al, 2018) so it was interesting to observe the silence on this issue from midwives. The most obvious display of individual bias was found in Hassan et al (2020) from the comparison of black, Asian, Arab and bilingual healthcare professionals with white healthcare professionals' comments. White healthcare professionals' comments had overtones of stereotyping and judgement whereas quotes from non-white British clinicians cautioned against stereotypes and were more proactive and sensitive in nature. Midwives reported that exposure to different cultures, faiths and quality learning tools enabled them to be more sensitive to women's diverse needs (Goodwin et al, 2018). However, training was reported to be inadequate, and midwives recommended training content that included lived experiences (Hassan et al, 2020). This study found a positive correlation between healthcare professionals' exposure, training and understanding of different cultures with the ability see people as individuals. This is consistent with research (Devine et al, 2017) although extremely complex to address (Fitzgerald et al, 2019).

Culture vs professional accountability

Midwives appeared to be caught in an untenable position between two parts of their role. Midwifery is regulated by the NMC (2018; 2019) and unfavourable outcomes are investigated by the Healthcare Safety Investigation Branch (2020). Part of the role being regulated involves individualising care and advocating for women's choice, putting women at the centre of care, with the principle of partnership of care and responsibility with women (Royal College of Midwives, 2014; National Maternity Review, 2016). However, some women rejected the notion of having equal responsibility for their own care, instead choosing to default to family members for advice (Aquino et al, 2015; Goodwin et al, 2018). Midwives have a responsibility to ensure women are fully informed and are able to make autonomous, informed choices (NMC 2018). Midwives reported limited time and resources to make this happen (Aquino et al, 2015; Goodwin et al, 2018) and described dominating male partners and mothers as negatively influencing their ability to do this (Goodwin et al, 2018; Hassan et al, 2020).

Furthermore, the papers cited issues such as fasting, poor antenatal attendance, smoking, mistrust of services, choosing to decline male clinicians or immediately washing or giving honey to a newborn (Richards et al, 2014; Aquino et al, 2015; Goodwin et al, 2018; Hassan et al, 2020). When women's preferences because of culture or religion diverge from NHS guidelines for maternity care, this creates tension because of the midwife's responsibility. This was most apparent in the data when faced with a life-threatening situation. For example, Hassan et al (2020) described a woman declining an emergency caesarean for religious reasons, which in UK law is her right (Mental Capacity Act, 2005). In the case of an unfavourable outcome, the midwife's clinical judgement will be investigated (Healthcare Safety Investigation Branch, 2020) whereas the woman will (rightly) not face the same scrutiny. These choices could be made by any woman and family, yet midwives are potentially less prepared for unfamiliar cultural or religious traditions (Goodwin et al, 2018). Midwives reported this creates anxiety (Goodwin et al, 2018) and directly contributes to health inequalities (Aquino et al, 2015).

Limitations

This study holds the potential for bias as the author is white British and practises midwifery in an area of the UK with a fairly low proportion of non-white British women, compared to the study areas cited in the papers. This was addressed by having input from supervisors and colleagues who are non-white British and Muslim when reading and reviewing the literature. This literature review was written for a university assignment and therefore co-authorship was not appropriate. The author has attempted to eliminate bias through extensive background reading and discussion of the findings with a research supervisor and colleagues; however, the review may have bias caused by single authorship.

Although the literature search covered the whole of the UK, three out of the four papers were research from England and one from Wales; therefore, this may not be representative of perceptions of midwives across the UK.

There is limited research that reflects the national picture of midwives' perceptions in more rural areas to compare to cities, which may impact the experiences and attitudes of midwives.

Conclusions

Midwives are committed to giving individualised, woman-centred care but communicate complex barriers that limit their ability to deliver this for non-white British women. Relationship breakdown and logistical issues are exacerbated by an us vs them divide between non-white British women and UK midwives. When midwives are required to meet the needs of women with unfamiliar cultures or traditions, they find their expectations of the relationship and care are immensely different to that of the women. This can impact the relationship that develops and the quality of care received.

Midwives seem largely unaware of their own unconscious biases and stereotypes. There is a lack of research into unconscious bias, which must be addressed to ensure that appropriate training can be given to minimise inequalities. Midwives must honour women's choices, which can be difficult when a decision is discordant with NHS guidelines or advice. However, midwives are strictly regulated and have concerns that they could be held responsible for an unfavourable outcome and therefore, women's choices can become the enemy of midwives' professional accountability.

Recommendations

The data show that the woman-centred, individualised care that midwives intend to provide becomes distorted by the barriers described in this review. To reverse this process, the author recommends that the issue be be tackled from the opposite viewpoint. For example, by aiming to reduce the barriers that inhibit midwives providing care that they are accountable for, including the subtle and less spoken about issues of structural racism, stereotypes and implicit bias. This would inevitably involve allocating more time to appointments where there are extra cultural or language needs, as well as improving the provision of implicit bias training to midwives.

Further research is needed to evaluate health information channels for women who are unfamiliar with the NHS. This may enable the creation of a national strategy that could set expectations of services in multiple languages to ensure women understand the role of healthcare professionals and expectations of themselves. Trusts need to be able to facilitate antenatal care for families, not just women, to recognise the needs of an individual woman in her own context. A financial strategy needs to be prioritised to meet extra demands of time and resources.

There is a lack of research into the direct effect of implicit racial bias in maternity services in the UK. Given the substantial inequalities and international evidence to justify this research, it is important that this research is undertaken. Further research is needed to determine the effectiveness of training that incorporates lived experiences and real-life stories compared to current ethnicity and diversity training. In the USA, neuroimaging techniques have been used to understand the biological and physiological mechanisms of bias as well as research the long-term effectiveness of interventions to address implicit bias (Devine et al, 2012). Chekroud et al (2014) recommend future research using neuroimaging that could determine strategies to prevent or reduce bias. Investment is needed to fund research that can deliver long-term strategies to counter the impact of implicit bias and systemic racism for non-white British women.

It would be helpful to have clear guidance for midwives on how to fulfil professional responsibilities and record this appropriately in a situation where women's choices because of cultural or religious practices diverge from the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence guidance. Midwives need to know that they will be supported when advocating for women's informed choices and that this will be considered a significant factor in clinical investigations.

Key points

- Midwives report being committed to delivering quality, woman-centred care for women who are not white British, even in situations where resources are scarce or the practicalities of care are logistically difficult.

- Midwives are aware of differing expectations between women and themselves; however, there is a lack of awareness of the impact of structural racism, stereotyping and implicit bias that affects the life experience of women who are not white British.

- There is a significant lack of support and training for midwives to address this; current models of cultural competency training are not adequate.

- Midwives are acutely aware of their professional accountability and report pressure of this accountability causing complications in the delivery of woman-centred care where women's choices conflict with guidelines.

CPD reflective questions

- Has reading this paper made me feel uncomfortable? Have I felt the need to justify myself or my practice or felt frustrated towards others?

- How has my training prepared me for meeting the needs of women who are different to me?

- Where are my own biases? Try the Harvard Implicit Association Test

- When I listen carefully to myself giving women information, is there anything I miss or explain more briefly for some women and not others? If so, why is this?

- What is the best way to open discussion with colleagues around stereotypes to enable women to be seen as individuals?