Male circumcision or the removal of the foreskin holds a deep spiritual significance in Judaism and Islam. The Judaic origins are reflected in our language as no other part of the human body is afforded a negative prefix, as in ‘uncircumcised.’

A better understanding of foreskin problems and the use of steroid creams for phimosis have led to a decline in the operation for medical reasons (Naguib et al, 2012; Hutson et al, 2015). However, the development of a more ethnically diverse society has led to an increasing demand for non-therapeutic circumcision (Stringer and Brereton, 1991). Sadly, the complications caused by unregulated practitioners documented by these authors have continued, with increasing concerns regarding sterility and infection control (Paranthaman et al, 2011; Poole, 2014). In England, community-based circumcisions have resulted in two recent tragic deaths, which involved unqualified personnel, poor communication and the failure to appreciate the dangers of continued blood loss (Fogg, 2012). Scotland has attempted to resolve such problems by requiring midwives to ‘ask all parents’ about circumcision at antenatal booking, ‘rather than presume someone's religion or belief’ (The Scottish Government, 2008). Religious circumcision is then offered free of charge under a general anaesthetic between the ages of 6 and 9 months (The Scottish Government, 2008). However, most approved services in the rest of the UK usually consider local anaesthesia up to 6 months of age as perfectly safe (Hutson et al, 2015). Midwives can help significantly by ensuring that information relating to such recognised providers is widely available.

The anti-circumcision movement

Anti-circumcision groups or ‘intactivists’ regard the operation as completely unnecessary, sexually damaging and a violation of human rights as the child cannot consent. They regard infant circumcision as child abuse and equate it with female genital mutilation. However, in 2011 an attempt to ban the procedure in San Francisco failed, and in 2012 an embargo by a district court in Cologne was later overturned by an embarrassed German government (Chambers, 2012). In October 2013, The Council for Europe, a human rights organisation, called upon European countries to ban circumcision for non-medical reasons as contrary to a child's right to physical integrity. The resultant furore from religious leaders led Israel to denounce the resolution as fostering ‘hate and racist trends in Europe’ and an ‘intolerable attack … on ancient religious tradition … and on modern medical science and its findings’ (Sherwood, 2013). The Council is now revisiting the issue.

Some Scandinavian countries, such as Norway, require those performing religious circumcision to be registered and, where necessary, to work under medical supervision (Siegel, 2014). However, in the UK, other than the necessity of complying with Care Quality Commission (CQC) standards, male infant circumcision remains unregulated and the number of non-therapeutic procedures unknown.

Groups choosing circumcision

As the neonatal period is recognised as the safest time for circumcision (Thalassis, 2009; Weiss et al, 2010; El Bcheraoui et al, 2014), midwives should be aware of those groups for whom it is important, so they can direct them to an appropriate regulated service. For Jewish people, the circumcision ceremony or bris milah is performed 8 days after birth by a mohel, someone with special training (Spitzer, 1996). Orthodox mohelim (plural of mohel) cannot circumcise a baby from a mixed marriage where the mother is not Jewish. However, in Reform Judaism, the religious guidelines are less strict and, unlike their orthodox counterparts, all their mohelim have medical qualifications. Both groups are often happy to circumcise children from non-Jewish families (Thalassis, 2009).

In Islam, circumcision is not mentioned in the Koran and is more of a cultural than a religious requirement. The timing is less precise, which causes problems when parents wait until a child is older, in which case a general anaesthetic is required. Faced with expensive surgery, parents may resort to traditional practitioners who advertise in newsagents or choose to organise a circumcision in their country of origin, where standards may prove less than ideal.

Male circumcision is prevalent in many other communities, including those ‘who are Christian, secular, or practice traditional religions’ (Thalassis, 2009: 12). It is common in the Philippines and in many West African countries, including Nigeria. In spite of some decline, South Korea maintains a very high rate of male circumcision, again involving children of school age (Kim et al, 2012). Parents from these backgrounds may be British citizens or have UK partners. Apart from religious reasons, neonatal circumcision is uncommon in the UK. However, in the USA the procedure is still popular, with about 60% of all newborn males being circumcised (Mielke, 2013). Recent hospital surveys indicate a decline, but with earlier postnatal discharge, many circumcisions now occur outside a hospital setting (Mielke, 2013).

An important paradox

There is, however, an important paradox, in that while non-religious neonatal circumcision has declined in the UK, recent scientific evidence has demonstrated that the procedure has important health benefits. The American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP), supported by associate organisations in obstetrics and urology, has concluded that: ‘The health benefits of newborn male circumcision outweigh the risks and justify access to this procedure for those families who choose it’ (AAP, 2012: 778). The European response has been to denounce the report of the AAP task force as ‘culturally biased’ and leading to ‘a flawed understanding of what constitutes trustworthy evidence’ arising from the ‘normality of non-therapeutic circumcision in the US’ (Frisch et al, 2013: 798). However, the AAP responded by stating that as the proportion of circumcised to uncircumcised men is more balanced in the US, their position was likely to be neutral, unlike Europe, ‘where there is a clear bias against circumcision’ (AAP, 2013: 801). Recently, draft recommendations from the Centres for Disease Control and Prevention (2014) have strongly endorsed the AAP's position.

Medical benefits (Table 1)

| Significant protection against heterosexually transmitted HIV |

| Protection against sexually transmitted infections, including syphilis and a reduction in bacterial vaginosis and trichomoniasis in female partners |

| Protection against the herpes simplex virus (HSV-2) |

| A reduction in the incidence and transmission of human papilloma virus, which causes genital warts and cervical cancer in the female partner |

| Significant protection against penile cancer |

| Prevention of foreskin problems, such as: balanitis, phimosis, paraphimosis and balanitis xerotica obliterans |

| Protection against urinary tract infection, especially during the first year of life and in those with urinary tract abnormalities |

| Some protection against prostate cancer |

Circumcision offers protection against sexually transmitted infections (STIs), especially HIV. Evidence from three large randomised controlled trials in sub-Saharan Africa confirms that circumcision reduces heterosexual transmission of HIV by 60% (Auvert et al, 2005; Bailey et al, 2007; Gray et al, 2007). There are several biological explanations as to why circumcision might reduce the risk of acquiring HIV (World Health Organization (WHO), 2007; Liu et al, 2013):

WHO (2008) actively promotes circumcision programmes in afflicted areas. However, the AAP (2012) recognises that the mode of HIV transmission is somewhat different in western societies, and the impact of circumcision less dramatic. Wright et al (2012) suggest some protection against prostate cancer, while Arya et al (2013) consider that the recent increase in penile cancer in England is linked to a reduction in childhood circumcision. Pinty et al (2014) also confirm the protective effect of circumcision against syphilis.

Providing information

In the UK, little information is available for parents interested in circumcision, whether for religious, family or health reasons, and most books on childcare simply ignore the subject. An exception is the excellent resource provided by the Greater Manchester Safeguarding Children Partnership (2013). However, outside areas of high ethnicity, little awareness of the subject seems to exist even among health professionals, as seen in the personal comments below:

‘On the two occasions that I mentioned circumcision to my midwives, I was met with a blank look.’

‘Midwives, in my experience, have little or no information on circumcision.’

Mothers enquiring about the procedure on parenting websites usually meet a predictable pattern of response: some initial support followed by a deluge of negative and hostile comments. The frequent declamation of circumcision in the media and the perceived negativity of health professionals may discourage parents from seeking medical advice and make them more inclined to resort to traditional practitioners. Thalassis (2009) notes that parents often delay circumcision because they are fearful and unable to find the right provider.

In the UK, all health professionals, whatever their own feelings on the issue, have a duty to respect parents' views. In primary care, midwives are now the main providers of maternity services and should possess some knowledge and information regarding neonatal circumcision. Parents who fear disparagement from medical professionals will appreciate the opportunity to discuss the subject with their midwife in the antenatal period. This gives parents time to consider their options, whereas a lack of information effectively denies choice and may prove dangerous. Families from mixed ethnic backgrounds in particular may need advice and support as one parent may lack understanding of the procedure. Midwives may worry that discussion may be seen as a recommendation, but there is no evidence from the Scottish model to support this.

Methods and risks

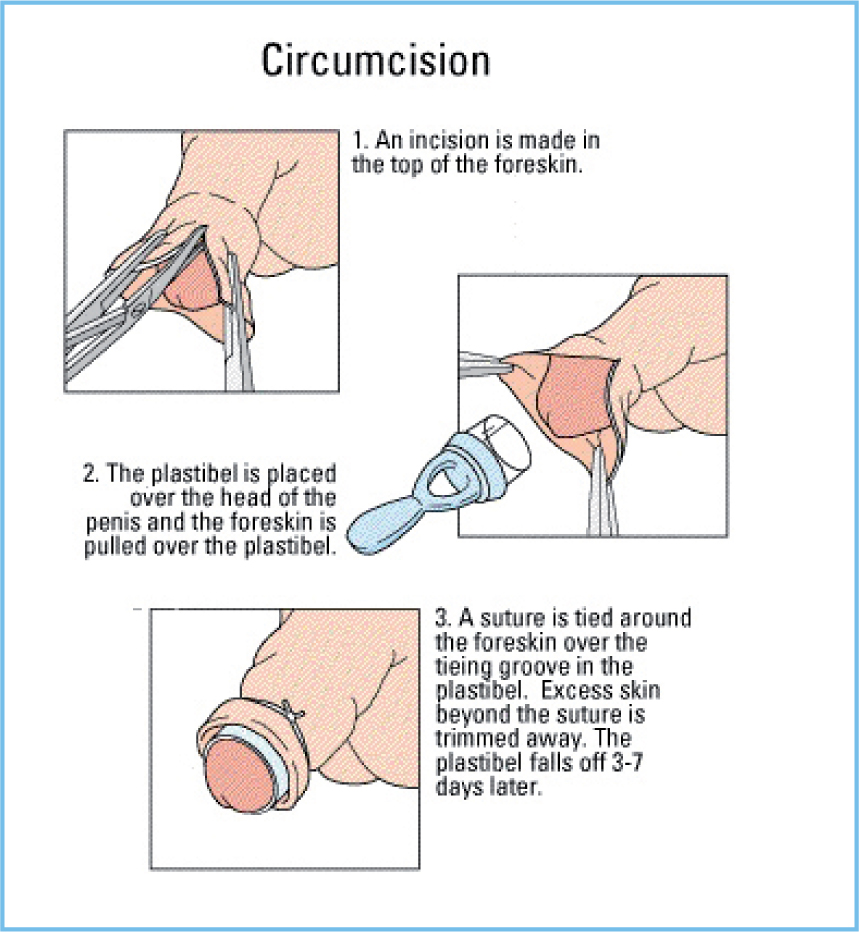

Two main methods of infant circumcision are used in the UK, namely, the Plastibell Circumcision Device (Figure 1) and the traditional Jewish shield (Figure 2); these are discussed in more detail below.

Plastibell Circumcision Device

The prepuce is incised and a grooved plastic ring of the appropriate size is inserted between the glans and foreskin. A special thread is securely tightened in the groove and the foreskin excised distal to the device. The ring separates with the remaining foreskin in 3–10 days. The Plastibell Circumcision Device has several advantages:

If the ring does not separate within the required period, the string may need tightening. Failing that, surgical removal will be necessary. Immediate attention is required should the plastic ring slip behind the head of the penis. The procedure takes about 15 minutes and follow-up by telephone is usually all that is needed. Parents are generally not allowed to be present, but should remain in the clinic with their child for about an hour afterwards to ensure no bleeding occurs.

Jewish circumcision shield

The prepuce is pulled through a longitudinal slit in a flat, stainless steel shield and excised. When the foreskin is cut across, the outer layer retracts to reveal the inner mucosal layer, which needs to be separated from the glans. The objective is to achieve sufficient removal of both layers so that approximation and healing takes place behind the head of the penis, so as to reduce the risk of adhesions.

To aid haemostasis, a bandage needs to be applied; this requires skill and experience. Occasionally, the frenal artery may require suturing. Bleeding is the most common complication, particularly slow oozing, which requires vigilance. Experienced mohelim can complete the procedure in minutes and are accustomed to operating with an audience. Jewish practitioners perform home circumcisions, but will require someone to hold the baby. The dressing, which should not be so tight as to restrict the passage of urine, is removed after 24–48 hours. Some creamy discharge is normal. As sutures are not used, the apparent loss of skin on the penile shaft may alarm those unaccustomed to the procedure, but healing is rapid and usually complete after a week. Close monitoring is required (Spitzer, 1996).

Aftercare

With both methods, aftercare involves checking for bleeding and infection and ensuring that the child is well and passing urine. Using larger nappies can reduce chafing. The frequent application of petroleum jelly or moisturising creams to the glans via gauze squares may help prevent meatal stenosis (Hutson et al, 2015).

Complications

El Bcheraoui et al (2014) document complications for neonates of less than 0.5%, whereas Weiss et al (2010) suggest the complication rate for neonates is 1.5% compared with 6% for children aged over 1 year. Nearly all of these were minor, involving infection or bleeding, which was easily controlled. Injury to the glans and serious complications are extremely rare. Sometimes, too much or too little skin may be removed leading to adhesions or a secondary phimosis (Williams and Kapila, 1993). Meatal stenosis is a late complication where the urethra becomes narrowed owing to repeated inflammation, and urine is passed in a thin stream. Surgery is usually required (Hutson et al, 2015).

Midwives should discuss the following points with interested parents:

After 6 months of age circumcision usually necessitates general anaesthesia (Hutson et al, 2015). Parents, therefore, should note the provider's stipulated age range and book early to allow for illness; several clinics use the Plastibell with older children. Although some men regret being circumcised and may seek foreskin restoration, a recent meta-analysis has confirmed that circumcision, particularly in infancy, has no effect on sexual function, sensitivity or satisfaction (Morris and Krieger, 2013).

Accessing a safe and proficient service

Midwives should be aware of reputable circumcision services, especially those with NHS Trust approval or that are free for local residents. As provision tends to be concentrated in areas with a high ethnic population, parents living outside of these areas may need to travel. Many clinics accept clients from all over the UK and Europe. Most providers are GPs who have been trained to use the Plastibell or consultant surgeons with paediatric expertise.

Personal recommendation is important but the internet can be helpful for those looking to find UK providers. Many have comprehensive websites, which give details of all aspects of the procedure, including aftercare and feedback. These providers should be registered with the CQC, and action may be taken against those who fail to maintain acceptable standards. Internet sites need careful assessment. Generally, the more information given the better. Full details should be provided on the procedure, potential side effects and advice on aftercare. Important points to note are:

Conclusions

The neonatal period is recognised as the safest time for circumcision and, in experienced hands, the risks are minimal. Midwives are ideally placed to offer an antenatal discussion so that interested parents have time to consider the issues without being rushed into making a decision or postponing one that they may later regret. The widespread provision of information by midwives relating to reputable circumcision services may ultimately reduce complications and save lives.

| The Care Quality Commission (CQC) is the independent regulator of health and social care services in England. It monitors and inspects services to ensure fundamental standards are met. Similar organisations exist in Scotland and Wales. |

| Circumcision services |

| The AMS Clinic at Bradford has CQC approval and a comprehensive website: www.amsclinic.co.uk |

| The Greater Manchester Safeguarding Children Partnership provides a list of quality assured non-therapeutic circumcision services, available up to 12 months of age. There is a yearly review and feedback is encouraged: www.gmsafeguardingchildren.co.uk/projects/circumcision |

| The Birmingham Circumcision Clinic (Vitality Medical Services) has CQC approval and provides circumcision services for infants, boys and men: www.circumcisionbham.co.uk |

| The Birmingham Circumcision Clinic (Newport Medical Group) runs a circumcision scheme on behalf of the Heart of Birmingham and South Birmingham Primary Care Trust, with a free service to local residents up to 12 weeks of age: www.birminghamcircumcision.com/index.aspx |

| Children's Circumcision Service Leeds is a private community-based service: www.circumcisionleeds.com |

| The Ashton View Medical Centre offers a free service for children up to 12 weeks who are registered with a GP in Leeds: www.ashtonviewmedical.co.uk/circumcision-minor-surgery-clinics.html |

| The Northern Circumcision Clinic in Sheffield has CQC approval: www.northerncircumcision.com |

| The Eastville Medical Practice in Bristol provides a service to all children between 1–6 months registered with a GP in the South West. Their website acknowledges NHS Trust support with details of practitioner training, the number of procedures performed and complications: www.eastvillemedicalpractice.co.uk |

| There are several clinics in London, including: |

| The Oakdin Circumcision Clinic is a private circumcision service in Essex: http://circumcisionprocedure.co.uk |

| The Circumcision Clinic at The Portland Hospital has a comprehensive website, with a Plastibell service for babies up to 8 weeks. |

| The Weston Surgical Centre in Stoke has CQC approval and the appropriate clinical personnel to offer general anaesthesia. |

| The Sternberg Centre in London provides a list of members of the Association of Liberal and Reform Mohelim. |

| Orthodox practitioners can be contacted through a local synagogue or the Initiation Society website: www.initiationsociety.org.uk/mohel.htm |