The recent removal of statutory supervision for midwives has left maternity care managers with responsibility for ensuring that alternative processes of guidance are introduced to improve the quality of maternity care provided by midwives.

Although the statutory elements of supervision have been disbanded in the UK, this does not signify the end of supervision for midwives. NHS Education for Scotland (NES) has co-ordinated the development of a new supportive system of supervision that has now been rolled out over Scotland. The aim of the new Scottish Clinical Supervision Model is to equip midwives to provide improved services, safer care and better outcomes for women and families through encouraging advocacy and accountability in keeping with professional regulation.

Changes to regulation of supervision in midwifery (Nursing and Midwifery Council [NMC], 2017a) provided the opportunity to adopt a refreshed approach that focuses upon supporting midwives to reflect on clinical practice, at the same time as developing resilience. This new model takes a compassionate and person-centred approach, which is a departure from the prior NMC supervision model. As part of the process, this new model incorporates coaching methods designed to help midwives respond, reflect, and restore self.

This article is designed to capture the processes involved in the Scottish Clinical Supervision Model (NES, 2019a). The first and second authors directed its development in conjunction with a steering group. The underpinning education surrounding the new model can be accessed at: https://www.nes.scot.nhs.uk/education-and-training/by-theme-initiative/maternity-care/about-us/clinical-supervision.aspx.

The overarching aims of the Clinical Supervision Model are to:

Why is clinical supervision important?

The NMC and Health and Care Professions Council (HCPC) for pre-registration midwifery both request that clinicians reflect upon practice during revalidation (NMC, 2017b; HCPC, 2017). The Scottish government documents Everyone Matters: 2020 Workforce Vision and Rights, Relationships and Recovery highlight the need to support and develop midwives using a model that embraces reflective practice (Scottish Government, 2010; 2013).

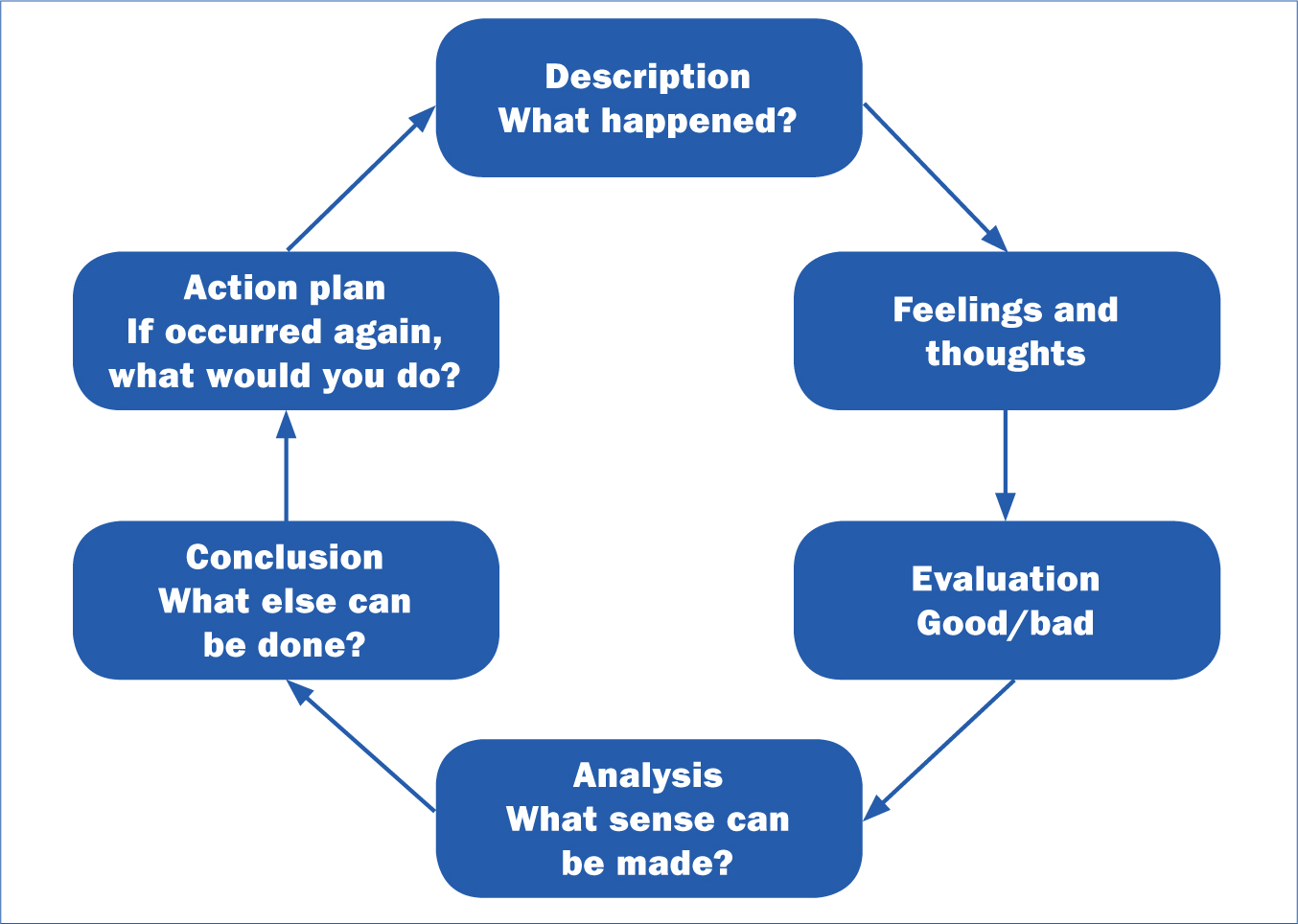

The Scottish Clinical Supervision Model has been designed to acknowledge stressors that impact upon midwives' personal wellbeing and is intended to improve self-care and enhance staff morale (Scottish Government, 2017a). The new model promotes exploration of clinical incidents, whilst taking into consideration emotions aroused during an interaction or clinical event. Supervision in this context involves a restorative component, which encourages the midwife to communicate more effectively through exploration of scenarios (Raab, 2014). The supervisor encourages the supervisee or group of supervisees to engage with the points illustrated in Figure 1 (NES, 2019).

Processes involved in supervision

Processes involve examining aspects that have touched the midwife emotionally. Emphasis is placed upon improving coping strategies and reducing compassion fatigue that stems from emotional, psychological, physical and spiritual exhaustion, which together and if ongoing can progress burnout and impact upon performance and levels of kindness shown to others (Klimek and Singer, 2012; Beaumont and Hollins Martin, 2016).

Essentially, the Scottish Clinical Supervision Model has been designed to encourage midwives to reflect upon practice-based events within a safe environment, with learning gained designed to reduce work-related stress (Bishop, 2006; Wallbank, 2010). As such, the benefits of ‘supervision’ are about developing a ‘super form of vision’, during which the midwife can take a fresh look at a self-selected experience (Care Quality Commission, 2013). In addition, the restorative component helps equip the midwife with improved coping skills to better manage taxing clinical work (Sheen et al, 2014).

To maximise effectiveness, clinical supervision should take place in a safe space and use a structured reflection framework. When used, the midwife requires to be mutually supportive to peers, which involves being open to questions and challenge and being accountable. Clinical supervision involves reflecting upon events and examining what went well or otherwise and how improvements can be made. The Scottish Clinical Supervision Model should not be used as:

The process should be guided by a trained supervisor who understands how to use a reflective model in the context of clinical incidence, with emphasis placed upon improving the supervisee's ability to provide care.

Setting up a system of clinical supervision

The responsibility for setting up a system of clinical supervision rests with the delegated member of the organisation. It is recommended that sessions are approximately one hour a month and led by a named supervisor.

In Scotland, each health board is responsible for organising their own supervision framework. Therefore, the style of delivery may differ between health boards, with each independently responsible for selecting their own lead supervisor and system of delivery. Factors for consideration include whether supervision takes place during the midwives' working hours, and in groups or on a one-to-one basis. Group versions are negotiated, with some members electing to attend by Skype. These groups are often fixed, with change of members negotiated democratically. New supervisors are midwife volunteers, many of whom have worked in the old supervisor capacity. NES offers ongoing supervisors workshops, and there is online training available (NES, 2019a).

Each health board is responsible for ensuring their staff are prepared and supported for their new role. At present, there are no formal assessments for qualifying as a new-style supervisor, and midwives select one from those available. A positive and quality relationship between supervisor and supervisee is essential to ensure effectiveness of the supervisory process, with midwives free to change their supervisor in certain circumstances. In the event that disharmony arises between supervisee and supervisor, either can reasonably request a change through negotiation with the health board supervisory lead. It is preferable that together they negotiate their own way through any issues together. Supervision is intended to yield:

Managers require to stipulate requirements for supervision in local policy and develop a system of documenting evidence of participation. Documenting events will allow revalidation and assessment of progress in relation to matters discussed.

Completing a training programme will strengthen supervisors' skills and ensure that they all have similar knowledge. Supervisors also require to be trained in management of group dynamics and how to apply reflective models. Proctor's Functions of Clinical Supervision Model is one of several tools that a supervisor can use (Proctor, 1988). This model outlines a process of normative accountability, formative (learning), and restorative (support):

Steps involved in the Scottish Clinical Supervision Model

There are five steps in the process (Table 1). The first involves writing a contract between supervisor and supervisee.

| 1. Writing the contract: |

4. Building a bridge: |

| 2. Maintaining focus: |

5. The review: |

| 3. The importance of space: |

Writing the contract

Before supervision commences, a contract is drawn up between supervisor and supervisee which establishes ground rules and priorities for discussion (Page and Wosket, 2001). This process involves discussion of ground rules, boundaries, accountability, expectations, and the relationship between supervisor and supervisee.

Examples of events appropriate to bring to supervision include a case study, a critical incident, an ethical issue, a legal matter, a reported event, a documentation issue, a clinical skills event, a decision-making difficulty, a confidence or competence struggle, a current topical event, a policy relating to maternity care, a leadership struggle, a career aspiration, or an issue of professional self-care. At the start of the supervision process, it is important for supervisor and supervisee to negotiate some ground rules.

Ground rules

The contract should reflect organisational and professional values (Hawkins and Shohet, 2012) and outline purpose, regularity, duration, location and the circumstances when it is acceptable to cancel a supervision session (Cassedy, 2010).

Expectations

The key purpose of writing the contract is to clarify expectations from the supervision relationship, with expectancies including:

Boundaries

It is key that the supervisor (leader) maintains conversations within professional boundaries and respectfully challenges behaviours or values that raise concern, where necessary. If group supervision is the selected method, it is important to consider whether members are open to new midwives joining and how this process will be managed, what constitutes respectful communication and how topics are chosen. Contracts will not ensure trusting participation, but negotiating and declaring them is an opportunity for clarifying intention and expectations (Proctor, 2011).

Accountability

The supervisee is accountable for outlining a clinical incident for exploration and listing objectives for the supervision session. The supervisee should be encouraged to explore what they believe should have happened and apply learning from prior sessions. At subsequent meetings, the incident is further explored to reflect upon new learning applied and whether what was hoped for was actually achieved.

Relationship

It is important for supervisor and supervisee to be open to questions and feedback, which requires skill on behalf of the supervisor because they are senior in the hierarchical arrangement. The supervisee giving feedback to the supervisor about their facilitation style is also of value. For example, what did they say or do that was most or least helpful? The supervisee should be the one to:

It is important to note that there are differences between non-directive and directive approaches (Table 2)

| Non-directive (facilitating) | Directive (mentoring) |

|---|---|

| Active and constructive listening | Advising |

| Reflecting back and clarifying | Giving feedback |

| Summarising | Instructing |

| Asking questions and exploring | Suggesting |

| Affirming | Sharing ideas |

| Empathising |

Maintaining focus

Issues

There may be barriers towards implementating a new clinical supervision system (NES, 2019). For example, some midwives may feel ambivalent towards the new model or be resistant to it. Objections may include time restrictions, staffing, or implementing a poorly facilitated and unstructured supervision model.

Objectives

To assist the supervisee to narrow focus and enable depth of exploration, the following questions may be useful:

It is important to outline and confirm the objectives of the session before proceeding.

Presentation

There are a variety of tools that the supervisor can use to aid analysis of the chosen clinical scenario. For example, the ladder of inference (Table 3) is an effective tool to aid understanding of why people instigate conflict with each other and fail to resolve the situation (Argyris, 1970).

| Actions |

You colleague says to you: ‘You managed that situation just the way I expected a midwife in this unit would!’ | Actions |

When your colleague suggests that you work with her on a project, you engage because you think she values your standard of work |

| Beliefs |

You believe that your new colleague has insulted you by stating that the midwives in this unit are incompetent | Beliefs |

You interpret that your new colleague has complemented both yourself and your peers through stating: ‘You managed that situation just the way I expected a midwife in this unit would!’ |

| Conclusions |

You conclude that the level of your work is not up to scratch, and that perhaps the unit is substandard | Conclusions |

Your new colleague concluded that the level of your work will be similar to the high standards of your colleagues |

| Assumptions |

You assume that your colleague values her own skills and training more highly than yours | Assumptions |

Your colleague assumes that you are good at your job because she has been impressed by the high quality skills of your colleagues |

| Meanings |

When your new colleague suggests that you work with her on a project, you make an excuse not to engage because you think she is just being polite | Meanings |

Your colleague asked you to work with her on the project because she meant it when she said: ‘You managed that situation just the way I expected a midwife in this unit would!’ |

When a conflict scenario is raised, the supervisor guides the midwife to work down the ladder of inference to explore each stage of ‘what’ they were thinking and ‘why’ in the situation. Together, they then progress back up the ladder as they develop a new sense of reasoning.

For example, consider a time you found yourself confused about why another person interpreted something you said in a way you never intended, or a time when you found yourself annoyed by another person's comments or behaviour and concluded that they do not like you. The ladder of inference is a way of describing how the supervisee can move from a comment to conclusion through progressing a sequence of mental steps. It is important to avoid climbing The ladder of inference in a direction that leads to detrimental conclusions, and simply accept that drawing inferences from what others say or do is based upon past experience. Also, the possibility should be considered that assumptions made by the supervisee may actually be correct.

Priorities

It is important for the midwife (supervisee) to prepare for each supervision session, with ground work promoting more efficient use of time and facilitation of a more considered reflection. Preparation may include:

The importance of space

Time, privacy and a suitable environment are key components of creating space to support effective supervision (NES, 2019a).

Collaboration

A collaborative and trusting relationship is necessary for supervision to be effective and successful. The Scottish Clinical Supervision Model emphasises three elements that are designed to build resilience: respond, reflect and restore.

The goal is to build resilience through exploring reflections upon a clinical event, how the supervisee responded, why they responded as they did, and attempt to restore emotions to a comfortable position during the process. After responding and reflecting, the restore component involves the supervisor placing emphasis upon processing emotions and building the supervisee's resilience to cope with similar events in future.

The restore approach is designed to help clinicians become more effective in the workplace. This is expected to reduce sick time and improve relationships with colleagues (Wallbank and Woods, 2012). In the role of facilitator, the supervisor does not make the choices. Instead, their role is to create opportunity for the midwife to select options and appropriate responses.

Investigation

The key rationale for reflecting upon practice is because experience alone does not lead to insightful learning (Loughran, 2002). The supervisee is not simply reflecting upon past actions and events, but also taking a conscious look at their emotions, experiences and responses in attempts to reach a higher level of understanding (Paterson and Chapman, 2013).

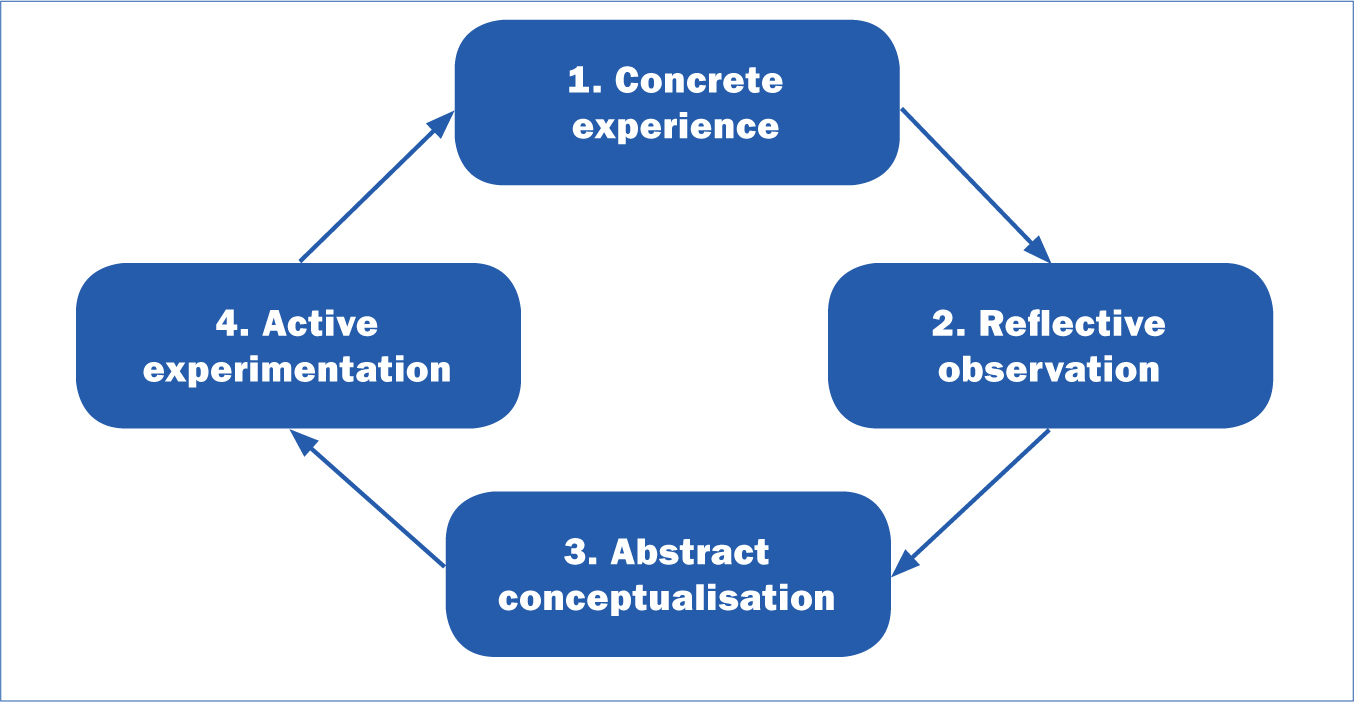

It is important to note that people repetitively engage in self-limiting behaviours due to preferred ways of thinking and responding (Turesky et al, 2011), with challenges to concepts and assumptions helpful towards breaking these cycles (Helsing et al, 2008). It has been shown that learning organisations which have invested in supervision processes that engage reflection on practice are more effective at inaugurating change (Aviolo et al, 2010). Reflection that is well conducted can shift anxiety into positive energy for action and address the gap between actual and desirable practice. From the many reflective models available to aid analysis of a scenario, two options are presented:

Challenge

During critical analysis, it is important to facilitate the midwife to explore issues from several perspectives before action planning. Useful questions begin with ‘what’, ‘how’ or ‘when’. For example (Kolb, 1984):

Containment

The supervisor has responsibility for organising a safe space in which supervision can take place with minimal interruption (NES, 2019a). In this space, the supervisor must be totally present and remind self in advance of key points from prior discussions. The supervisor must maintain confidentiality, be reliable, adhere to agreed appointments, and be mindful of the pre-written contract. It is important that the supervisor identifies and acts appropriately regarding unsafe, unethical or illegal practice. Emotions expressed should be contained within this safe space.

Affirmation

It is important to provide affirmations, such as assertions, support, verification, confirmation and encouragement (NES, 2019a). Given this support, the supervisee is more likely to reflect upon values and is less likely to experience distress and react defensively when confronted with information that contradicts or threatens their sense of self. Such affirmations help coping with threat or stress and as such act towards improving performance.

Building a bridge

At the end of the supervisor session, it is important for the midwife to leave with a clearly summarised picture of events (NES, 2019a).

Consolidation

To consolidate the supervision session, goal setting will facilitate the supervisee to identify what changes in practice are best and what they might look like (NES, 2019a). This involves them considering what they could be doing or how they may be feeling if they were to implement aspects surrounding the event differently.

Information giving

Having shared and researched information that relates to the incident explored, the following are addressed (NES, 2019a):

Goal setting

The bridge component of the supervision model is underpinned by motivation and jointly discussed goal-setting (NES, 2019a). Goal-setting involves setting objectives designed to improve subsequent performance. These goals should be set with clarity, challenge, commitment, feedback, and be relevant to task complexity.

Action planning

An action plan requires to be written which outlines steps required to reach the goals outlined (NES, 2019a). The action plan can be written as a sequence of steps taken to inaugurate change in practice. The supervisor and supervisee negotiate and agree the action plan outlined.

Client's view

The supervisor needs to place the supervisee at the centre of discussions and perceive them as an equal partner in planning, developing and monitoring the care they provide (NES, 2019). This involves placing the midwife at the centre of decision-making and seeing them as experts working alongside their supervisor to gain best outcome. Being compassionate and thinking about matters from the midwife's perspective is key during this process.

The review

Review and evaluation of prior actions can be achieved when the goals set are specific and measurable (NES, 2019). SMART is a useful acronym that can be used when writing objectives and stands for specific, measurable, achievable, relevant and time-bound.

Goals should have a distinct purpose and be written in a way that directs full completion of the task in hand (SAMHSA, 2019).

Feedback

The review offers opportunity to explore with the supervisee if objectives from prior supervision sessions are still relevant and if there is need or desire to continue with discussions surrounding chosen topics (NES, 2019a).

Grounding

The process can be challenging, simply because it requires the supervisee to share thoughts that may render them vulnerable. To gain the best from clinical supervision, it is key for the midwife to trust their supervisor. In response, the supervisor must treat any declarations with respect and confidentiality. Issues should only be shared post recorded agreement in relation to what will be disclosed and to whom (NES, 2019a).

Evaluation

Some form of standardised evaluation of the supervision process requires to be developed to measure benefits at both an individual and organisational level. Evaluations can be conducted verbally and through use of a structured survey (NES, 2019a).

Assessment

It is important to assess the supervisee's views of the supervision process and what has gone well and what has not, in relation to any decided actions taken post supervision (NES, 2019a). An assessment could involve the midwife writing a structured reflection on practice essay, using a reflective model, as outlined in Figures 1 and 2. Post completion, this essay may be placed in the midwife's personal portfolio and used as part of revalidation for the NMC.

Summary

These steps in the supervision process are cyclic, with supervision commencing at any point in the cycle. The processes involved in the Scottish Clinical Supervision Model have been summarised on a set of laminated cards that can be carried in the supervisor's pocket (Figure 3).

Conclusion

The Scottish Clinical Supervision Model is a refreshed approach to midwifery supervision that seeks to develop midwives' resilience and cultivate their practice, with the ultimate aim of improving services and providing safer outcomes for women, infants and families through reflection on practice. This new model takes a person-centred approach, which includes coaching methods that teach midwives to respond, reflect, and restore self.