Midwifery in the UK is underpinned by the Nursing and Midwifery Council's (NMC, 2018) ‘The code: professional standards of practice and behaviour for nurses, midwives and nursing associates’. ‘The code’ presents the standards and behaviours expected of midwifery professionals (NMC, 2018). Autonomy and the ability to act on one's professional judgement are integral to midwifery education and professional practice (NMC, 2018; 2019). As educated, competent professionals, midwives are known to reduce global maternal and neonatal mortality, and improve quality of care (Renfrew et al, 2014); thus, demonstrating the value of the profession to society.

The professionalisation of midwifery has followed a complex, turbulent course of development, which forms the sociological basis for contemporary care in pregnancy and childbirth. An exploration of the historical context of midwifery, government policy, risk, managerialisation, litigation and social media help provide a fundamental basis for sociological imagination.

Wright Mills (2000) highlights the importance of having a sociological imagination-a sociological term allowing the understanding of oneself in relation to historical and social context, to understand one's place in time, reduce bias and increase consciousness of oneself to allow the possibility of change. This sociological imagination facilitates an understanding of contemporary midwifery autonomy by examining how the profession emerged and has evolved, what the influences on professional autonomy have been and what they are now. This overview provides a critique of whether professional autonomous midwifery is achievable. This will be followed by another article focusing on a conceptual framework of midwifery autonomy as a conduit to women's autonomy.

Midwifery autonomy focus

The focus in this two-part article is on midwifery autonomy. Whilst evidence gathered focuses on the medicalisation of birth and its relationship with managerialisation, it is understood that midwifery is not alone in experiencing professional erosion of autonomy, and that medical professional control has similarly been eroded (Numerato et al, 2012). Savage (2011) writes that obstetrics is in a position that needs professional reclaiming to ensure the choice agenda. Whilst both the national and midwifery agenda is to provide women with choice, the difficulties obstetricians face in their own professional discipline is not separate to the problems highlighted. However, this is beyond the scope of this article.

Historical background: the context for contemporary care

Following centuries of debate, midwifery was born from a middle class ideal (Leap and Hunter, 2013). Despite midwifery's origins as a traditionally working class occupation, set aside from the feminist ambitions of medicine (Mander and Reid, 2002), a selection of well-connected women sought to create jobs for the middle class in order to emerge from their domestic or philanthropic roles (Witz, 1992). These women were influenced and encouraged by patriarchal forces (Mander and Reid, 2002) or the ‘institutionalised and systemic’ male dominance of power and social advantage (Witz, 1992). This was centred on women's failure and fallibility to both birth and to helping others birth as part of systemic gender oppression, which persists today (Jenkinson et al, 2017).

Witz (1992) explains that midwives were enabled to care for ‘natural cases’, with the expectation that obstetricians should be called to assist with the ‘unnatural cases’, to reduce the possibility of any intrusion of the medical profession. This provided clear demarcation lines of professional practice and the creation of a female workforce, supported by male medical professionals. The dual closure of the midwifery and medical professions from one another was achieved (Witz, 1992). The creation of the Central Midwives Board, following the First Midwives Act in 1902 (Leap and Hunter, 2013), enabled this and was highly influenced by medical colleagues.

The development of the Central Midwives Board's aim of ensuring safe practice was to be commended and has shaped contemporary midwifery practice (Leap and Hunter, 2013). Nonetheless, the ‘standard setter’ for midwifery has always been the obstetrician (Clarke, 2004). The medically dominated policies and procedures of institutions impact on the midwifery philosophy of care within current maternity practice. This leads to difficulties when midwives endeavour to provide informed choices and retain professional autonomy, while working within the policy framework (Newnham and Kirkham, 2019).

This is the result of recommended care being largely supported by medically imperialised guidance, which makes compliance in medicalised care an easier route for women and their care providers than opting for physiological routes (Newnham and Kirkham, 2019). However, society, professionals and government policy suggest that choice and autonomy should lie with women and their families (National Maternity Review, 2016) and not the professionals.

Government policy

Government healthcare policy from the 1970s portrays the great traction and importance that risk has acquired within the UK healthcare system. This presented challenges to healthcare organisations, practitioners, professionals and the public (Symon, 2006) and has an impact on the professional autonomy of midwives (Porter et al, 2007). Despite a lack of robust evidence, the Peel Report (1970) recommended that a hospital was the safest place to give birth (Olsen and Jewell, 1998). Consequently, a national change in routine birthplace occurred, undermining midwifery. The home birth rate dropped from 33% to 1.9% between 1960 and 1977 (Office for National Statistics, 2017). While women were still provided choice, the coercive control of medicine was clear (Nolan, 2010): women were expected to attend hospital for birth.

Changing Childbirth (Department of Health, 1993) highlighted the importance of women's choices and provided an ideology of the maternity services. Unfortunately, financial support for infrastructure changes were not provided and practice change did not occur (Thomas, 2002a). The choices proposed for women were pseudo choices within an unchanged medicalised system, creating groups of practitioners who attempted to offer more choice but had to conform to the same bureaucratic processes of the institution (Thomas, 2002b).

More recently, an important, statistically significant research study created a further opportunity for maternity services transformation. Brocklehurst et al (2011) studied over 64 000 women and found women without medical or pregnancy complications were as safe with midwife-led care as they were with obstetric care. In addition, they were at less risk of unnecessary medical intervention and associated morbidity. Hollowell et al (2015) confirmed these findings, supporting birth outside of obstetric units for healthy women and babies. Nevertheless, the National Maternity and Perinatal Review (2019) identified just 14.4% of women in England giving birth in midwifery led facilities or at home between 2016 and 2017 (latest report available), despite 36.9% of women in England birthing without intervention. Furthermore, the Care Quality Commission (2020) found that only 61% of women felt they had definitely been given enough information to choose their place of birth (from midwives or doctors) and 12% said they did not have enough information. Yet, an increased number of women reported choosing and birthing in midwifery care units in 2019 (Care Quality Commission, 2020), although actual numbers are not included, only information from survey responses.

The National Maternity Review (2016) echoed and developed the Changing Childbirth report, by incorporating the Birthplace study findings (Brocklehurst et al, 2011). The individual recipient of care is the pivotal point and the empowerment and informed choices of the recipient of care (the woman) are paramount. This aligns to the concept of ‘new professions’, where the professional and the client share power (Porter et al, 2007). Furthermore, research supports that women are most satisfied with their birth experience when cared for by a midwifery led model (Overgaard et al, nd; Mattison et al, 2018), in addition to feeling more in control (Renfrew et al, 2014). However, the demands of the public and management make public-sector professionalism a paradox (Power, 2008).

The government and research support for women's choice and midwifery led care is overarching; however, this is not mirrored in birth and care statistics. The medicalisation of childbirth and obstetric dominance shapes midwives' ability to retain autonomy in practice (Wong et al, 2017) and promote physiological birth. The lack of support from institutions is also acknowledged as a contributor to reduced autonomy (Wong et al, 2017). In addition, Newnham et al (2017) identified that informed choice was often unbalanced toward medicalisation on the delivery suite. The value of midwifery and obstetric respect and collaboration is recognised as a facilitator of autonomy (Hadjigeorgiou and Coxon, 2014).

Risk, managerialisation, litigation and the media

An important issue to consider is the influence the media has is in the depiction of professionals and the information shared about maternity care. While the media is often blamed for portraying birth as risky and needing intervention, midwifery engagement in the media can also be critiqued as lacking midwifery professional input (Luce et al, 2017).

Leachman (2017) identifies that society, through media, portrays birth as painful, in need of medical assistance in a hospital, with the woman on her back. The inaccurate information is not always aimed at the truth and supporting women, but at increasing media profits, which potentially causes inaccuracies and instils fear (Leachman, 2017), contributing to a false depiction of birth. Dahlen (2017) highlights that there is an increased media coverage of risk and bad news, because of the need for humans to avoid risk and death. Additionally, the obstetrician as ‘expert’ reinforces the hierarchy of medicine and the superiority of technology to the public (Dahlen, 2017), further contributing to societal perceptions of birth and the reduction of midwifery autonomy. The midwives' professional ethical responsibility for providing evidence-based healthcare is imperative (Nursing and Midwifery Council, 2018). Furthermore, government policy supports evidence-based healthcare (National Maternity Review, 2016).

Outlining benefits and disadvantages of care while contextualising these for the individual in light of current available research and information is imperative (Aveyard and Sharp, 2013). It is acknowledged that risks do not exist alone, but are dependent on other coexisting risks, and are altered by individual circumstances, meaning they should not be generalised (Beck, 2009). Irrespective, the art and skill of midwifery has been replaced by risk, control, surveillance and blame, in an attempt to reduce uncertainty in a society where it is given no place (Skinner and Maude, 2015). This perception of risk and the belief that medicalisation reduces risk undermines midwifery autonomy, and the overuse of birth interventions globally is known to be unnecessary (Renfrew et al, 2014).

Since the creation of the midwifery profession, power relationships between midwives and obstetricians have created professional conflict, leaving midwives feeling oppressed and obstetricians feeling like their medical authority is disregarded (Reiger, 2008). The global identification that some doctors are threatened by midwifery led care has been acknowledged by the World Health Organization International Confederation of Midwives White Ribbon Alliance (2016). Cramer and Hunter's (2019) recent thematic literature review identified the working relationships between midwives and medics as a source of stress and a contributor to burnout in midwives. The compilation of both more dated and recent literature highlights the difficulties that healthcare relationships present, both across professions and within midwifery. Additionally, the increasing permeation of ‘risk society’ erodes professional autonomy and exacerbates the friction between models of care, increasing the medical dominance of birth. The ability for midwives to provide support to women to make decisions about their care is further hindered by the culture and environment that midwives work in (Jefford et al, 2016).

The medical (techno-rational) model values productivity, efficiency and the bureaucracy that comes with this (Walsh, 2006). Newnham and Kirkham (2019) identify that midwives' and doctors' compliance with guidelines and institutionalised practice is considered more important than women's choice and is unethical. Women are subjected to risk assessment from early in pregnancy, according to their medical and pregnancy history (Healy et al, 2016). This risk discourse and the connotation of risk can have negative consequences on pregnant women and focuses on inevitability of risks, whether an individual believed that medical intervention and availability reduced these risks or not (Possamai-Inesedy, 2006).

Scamell (2014) examines the complexities of risk society in relation to childbirth, and identifies that both women and midwives contribute to the ongoing perpetuation of birth as risk. The focus on birth from a health perspective and the identification that the medical model increases risk (interventions), as well as reduces it, is an important perspective to embrace (Healy et al, 2016).

The medical model views childbirth as a pathology that needs to be mediated to reduce inevitable risks, whereas a midwifery (social model) views pregnancy and childbirth from a salutogenic perspective (Suominen and Lindstrom, 2008). Normal physiological processes are expected, unless, through vigilance and expertise, deviation is detected, resulting in action and referral (Walsh, 2006). ‘Risk Society’ has given rise to this culture of audit to increase quality care and mitigate risk (Shore, 2008). The increasing awareness of risk yet, concurrently, the demand for greater choices persists as part of the ‘risk-choice paradox’ (Symon, 2006). Lee et al's (2019) cross-sectional survey found that midwives evaluate risks as being higher than doctors in a comparative analysis, but that women have the highest perceptions of risk. However, all participants had different perceptions of risk (from both within the same group and across groups) and reported that professionals should engage in respectful communication and understand a women's perception of risk without making any assumptions (Lee et al, 2019).

Carson and Bain (2008) argue that risk is difficult to define, but should be used as an enabler rather than a disabler of the system. It is known that application of risk management strategies to learn from poor decision making can promote safety and avert unprofessional behaviour, without apportioning blame (Carson and Bain, 2008), and professionals can be held accountable for their actions. However, Beck (2009) identifies that no-one is not at risk, each person is either more or less at risk than another. Escalating risk awareness, illumination of healthcare scandals and increases in litigation cases have created a transition from professional self-regulation to risk management and scrutiny from external agencies (Spendlove, 2018), further hindering professional autonomy.

Following the women's rights movements of the 1960s and 1970s (Thomas, 2002b), maternity saw a change in professional behaviour from classical professionals (‘the professional knows best’) toward the new professional era (Porter et al, 2007). Porter et al (2007) identifies that midwives are controlled by bureaucratic processes exacerbated by inexperience. The safety net of guidelines and policy, provided by new managerialism, reduces the likelihood of shared decision making. Additionally, growing workloads because of increasing amounts of documentation as evidence of care provision fosters a stance of classical professionalism (Porter et al, 2007). However, there is little evaluation of the usefulness of guidelines, aside from reduced fetal movement (Jokhan et al, 2015) within the UK, and there is knowledge that guidelines can do harm (Woolf et al, 1999). Despite being dated, there is little research to support guideline use, but this is favoured by the Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists (2011). The professional super ordination of medics can either encourage or hinder new professionalism (Porter et al, 2007) and the historical subordination of midwives to medics may have rendered midwives more susceptible to submit to new managerialism (Witz, 1992). A more contemporary source highlights this ongoing theme through women's difficulty in accessing choice in maternity: the Association for Improvements in the Maternity Services, a campaigning charity for women in response to the MBRRACE report (Knight, 2019):

‘We know that many women are being forced into induction of labour in an attempt to reduce the number of babies who are stillborn, despite the lack of evidence of its effectiveness. This one solution may (or may not) solve one crisis but creates another, with the high possibility of physical injury and traumatic birth which can have devastating lifelong consequences for many women’

Furthermore, not all midwifery is deemed ‘good midwifery’ and can be judged as obstetric nursing because of fear of litigation, and highlights anxiety that midwifery will be consumed by the medical model of childbirth (Thomas, 2002b). This resonates with Miller et al (2016), as they found that a history of medical dominance compounded by an increasingly risk-focused healthcare is driving rising medical intervention rates. There is increasing medical dominance (Spendlove, 2018) and the woman's voice being lost (Edwards and Murphy-Lawless, 2006).

Defensive practice intensifies the compliance to non-individualistic care (Mahran et al, 2007). The rationale for maternity's risk-focused system is because of the enormous cost of maternity litigation claims. Despite litigation of less than 0.1% of NHS births, 20% of the total number of all clinical negligence claims are obstetrics and gynaecology in the NHS and they form a disproportionate 49% of the total cost (NHS Litigation Authority, 2012). The fear that litigation incites for staff working within maternity services results in practice alteration, including defensiveness, an adherence to policies and increased reliance on medical permission (Robertson and Thomson, 2016). The focus is guideline compliance, rather than care provision in the best interests of the care receiver (Robertson and Thomson, 2016), contradicting the professional duty to prioritise people by recognising diversity and individual choice (NMC, 2018). An anecdotal example of this is that many local NHS trusts advise all women giving birth after a previous caesarean to have an intravenous cannula ‘just in case’, without consideration of the individual risks. No evidence supports this practice; moreover, evidence suggests increased infection risks associated with intravenous cannula insertion (Bailey et al, 2019), despite this being common practice. This further demonstrates how institutional practice and guideline reliance erodes professional autonomy.

Robertson and Thomson's (2016) phenomenological research identified that following experiences of litigation, the relationship between midwives and women can be altered and confidence lost. An increased reliance on medical colleagues was found, yet only a minority of participants felt they had gained positive learning from litigation events, further signifying growing medical reliance. In response, time-consuming, increasing documentation levels are advocated, paradoxically reducing the amount of face-to-face care with women (Robertson and Thomson, 2016).

The infiltration of risk discourse and managerialism contributes to an ever-increasing dominance of the medical model (Spendlove, 2018). Autonomy reduction and reduced traditional midwifery practice has a direct impact on the professional status of the midwife and medical authority prevails (Spendlove, 2018), resulting in reduced individual choice for women. Additionally, Spendlove (2018) identifies the obstetric view of increasing medicalisation of childbirth has also been a de-skilling process for medics. Despite this, ethnographic research highlights that the midwifery professional boundary is being eroded by increasing medicalisation, and the obstetric professional boundary is becoming stronger.

Midwives feeling powerless because of a reduction in autonomy and feeling like they are held between the midwifery and medical model has been identified by Rice and Warland (2013). Having diminished autonomy is associated with reduced resilience (Hunter and Warren, 2014) and midwives' wellbeing is directly related to the levels of autonomy and support from colleagues and their organisations (Cramer and Hunter, 2019).

Conclusions

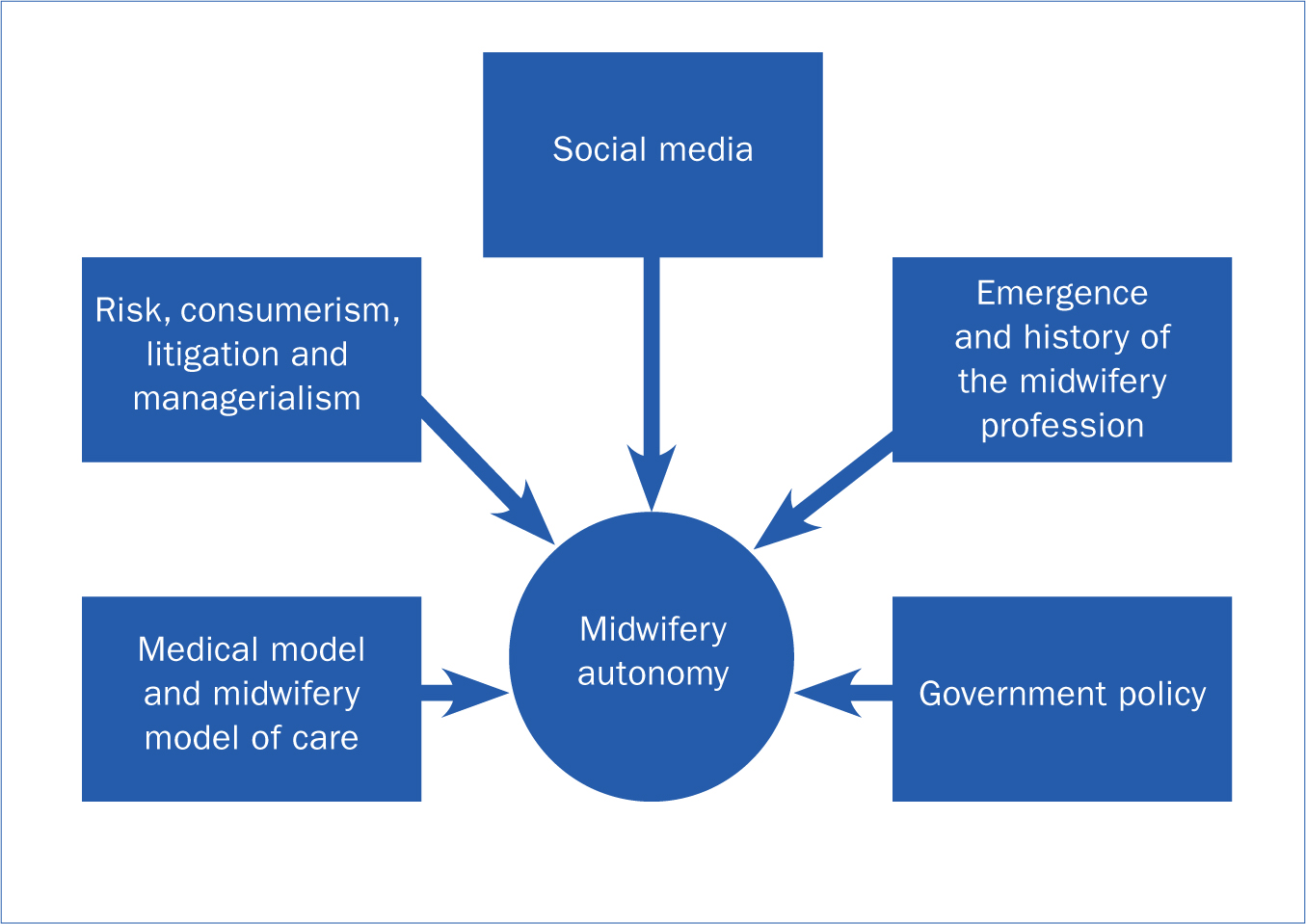

Figure 1 summarises the influences on midwifery autonomy discussed in this paper. The historical professionalisation of midwifery has had powerful influences exerted on it from the obstetric profession, which has shaped contemporary midwifery and reduced midwives' autonomy. Despite this, the NMC and government reports support the autonomy of midwives as a conduit to high quality, individual care for women, which includes informed choice. This is complicated by risk and litigation, which has exacerbated the reduction of autonomy through managerialisation.

Figure 1. Influences on midwifery autonomy

Figure 1. Influences on midwifery autonomy

Finding a way to navigate the complexities to serve the women for whom the service exists, retain quality of care, provide choices, and succeed in autonomous decision making is challenging but achievable. In part two, a conceptual framework has been devised to enable this, utilising the concept of ‘new professional midwifery’, following a discussion of potential service pressures, evidence-based care, consumerism, leadership and reflexive practice in an attempt to navigate professional autonomy and retain women's choice.

Key points

- Occupational closure of midwifery was influenced by patriarchal medical forces creating ongoing turbulence.

- The Nursing and Midwifery Council′s code advocates the need for midwives to be autonomous.

- Autonomous midwifery practice is challenging in the face of litigation, medicalisation of childbirth and managerialisation.

- The achievement of choice is advocated by the UK government but guidelines provide pseudo choices.

CPD reflective questions

- Do you provide women with choice?

- Do you consider yourself to be autonomous?

- Is your practice influenced by medicalisation of birth?