The proportion of mothers in the UK who feed their infants with infant formula has steadily increased (World Health Organization (WHO), 2021), Despite information campaigns about the importance of breastfeeding for reducing infant illness and mortality (WHO and the United Nations Children's Fund (UNICEF), 2003), rates of breastfeeding in the UK drop from 68% at birth to less than 50% at 6–8 weeks (Nicholson and Hayward, 2021). This places the national breastfeeding rates at one of the lowest levels internationally, higher only than the USA (Renfrew et al, 2012).

While many initiatives have attempted to improve breastfeeding rates in the UK (Shortis, 2019), decisions surrounding infant feeding tend to be made prior to pregnancy or in the first trimester (Sheehan et al, 2013) taking into account factors such as physical problems, embarrassment, social pressure, a lack of accurate information or partners being unsupportive of breastfeeding (Hauck et al, 2011; Oakley et al, 2014; Feenstra et al, 2018). A literature review of breastfeeding discontinuation before 6 months identified that a lack of support (either from significant others close to the breastfeeding mother or from health professionals), poor physical or emotional health of the mother and an insufficient milk supply were the main reasons, other than maternal choice, for early cessation of breastfeeding (Wray and Garside, 2018).

Mass media has been highlighted as an important sociocultural influence on breastfeeding in that it acts as a potential ‘proxy’ for a lack of real-life exposure to breastfeeding (O'Brien et al, 2017; Keevash et al, 2018) and influences public perceptions of infant feeding (O'Brien et al, 2017). The role of mass media in influencing breastfeeding behaviour appears to have improved over the years. A content analysis of British newspaper articles published in 2000 (Henderson et al, 2000) revealed that while the press were largely adhering to marketing guidelines surrounding infant formula (Legislation.gov.uk, 2007), general coverage was presenting readers with mixed messages about breastfeeding. A more recent review suggests that portrayals of breastfeeding are becoming more positive (O'Brien et al, 2017). Despite these improvements, research from Brady (2012), and more recent research from Hastings et al (2020) has identified many instances where marketing regulations of infant formulas are breached with few disincentives.

The present study aims to complement existing research by qualitatively exploring the influences of British media, particularly social media, on women's perceptions of breastfeeding and the impact this has on their choices and breastfeeding journey. This was achieved through an ethnographic interview approach with women during the early stages of their breastfeeding journey and those wishing to become mothers themselves.

Method

Participants

The inclusion criteria in group A were that participants were of childbearing age, who did not currently have children but had a desire to have children in the future. Group A consisted of nine women aged 19–28 years old. These criteria were selected because of the evidence that many women have tentatively made a decision regarding infant feeding prior to (or in early) pregnancy (Sheehan et al, 2013) and, therefore, any media influences on these women would be highly relevant to the research question.

The inclusion criteria in group B were that participants had to have had at least one biological child. No restrictions were applied regarding age or number of children or the feeding methods used. Group B consisted of 31 mothers (20–46 years old).

Participants were recruited through social media and came from across the UK. Recruitment took place between February 2014 and February 2017. Mothers in group B had between one and three children (aged between 8 months and 7 years of age), had breastfed their infants at some stage with a range of breastfeeding duration from a few hours to over 3 years (mean=12 months). Nine were still breastfeeding at the time of interview. Seven participants were from lower socioeconomic backgrounds.

Design and procedure

The study used an ethnographic approach to qualitative research using interviews to gain a comprehensive understanding of social phenomena (Reeves et al, 2013). Semi-structured phone interviews were conducted lasting 30 minutes to 1 hour.

The interviews were conducted by the first author, a former doula or by the second author, an academic psychologist with experience of qualitative analysis. Both interviewers were female, and both had children themselves and had experience of breastfeeding.

The interviews comprised two phases. The first phase aimed to establish existing general views, opinions and exposure to breastfeeding and formula use, and the second phase of questioning involved asking participants to discuss media footage. Mothers (group B) were also asked about their own experiences of feeding their infants, methods used and any influential factors they were aware of. Participants were then asked to discuss magazine, newspaper and social media articles, as well as television and film coverage of infant feeding issues (including incidental imagery and advertising) that they had encountered. They were asked to discuss their feelings about the content itself and reflect on how this impacted them in relation to their own experiences. Women with no children (group A) were asked about any conscious effect this had on their potential future decisions, attitudes and beliefs about breastfeeding.

Data analysis

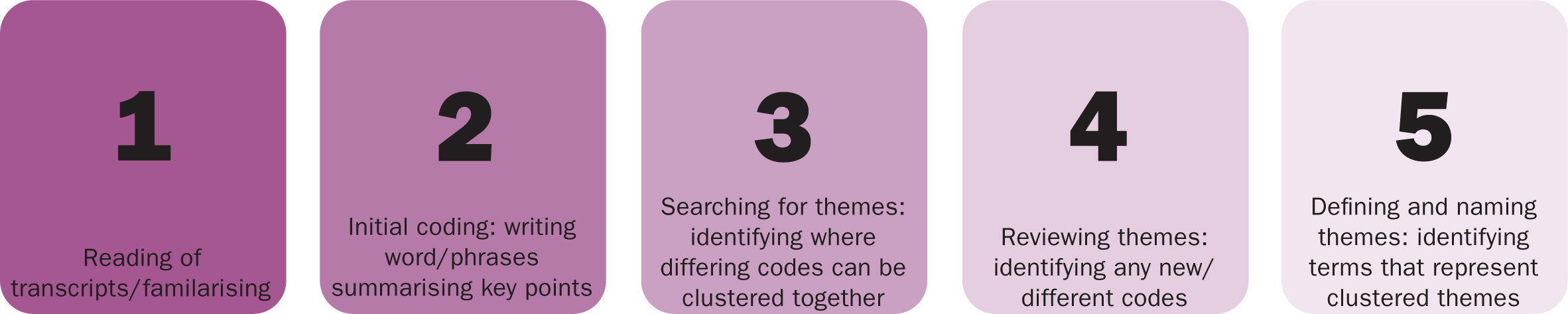

Interviews were transcribed and analysed using inductive thematic analysis (Braun and Clarke, 2006). This flexible form of analysis allows examination of themes relating to sociocultural influences, lived experiences and more implicit factors influencing breastfeeding attitudes and behaviours (Figure 1). The first and second authors independently read through an allocated number of transcripts each and familiarised themselves with the data. The researchers then reread each transcript in turn, identifying codes (words or phrases) that summarised points. The researchers independently revisited the codes and grouped them into meaningful clusters. For example, codes such as ‘intimate’ ‘personal’ and ‘too public’ were clustered together. Once transcripts had been revisited to ensure all codes had been identified, the themes were named. Validity checking was performed on the data, with the second author validating the analysis. Where any disagreements existed, these were passed to the wider research team for discussion. The transcripts and analysis were also sent to participants for member checking. These processes were employed to ensure rigour of data analysis. The authors used the Guba and Lincoln (1989) criteria in the design, collection, analysis and write up of this work to ensure rigour throughout the qualitative research process. The sample size was deemed sufficient as data saturation had been reached; no new themes or codes were identified in the last transcripts (Fusch and Ness, 2015).

Figure 1. Flow diagram of analysis process

Figure 1. Flow diagram of analysis process

Ethical considerations

Participants were fully informed of the nature of the study and their right to withdraw at any time. Participants consented to take part by reading an information sheet and providing written consent. The British Psychological Society (2021) guidelines of ethical research practice were fully adhered to and the study received ethical approval from the university ethics committee (reference number: 3371KS13/14). The participants were offered no incentives for taking part in the research.

Results

Five main themes were identified that influenced women's perceptions of breastfeeding and their planned or actual behaviour: family influence, privacy, media as a double-edged sword, negative exposure to breastfeeding and planned behaviour versus experience.

Family influence: ‘I always had it in my head’

The importance of exposure to breastfeeding in creating a normalised attitude was highlighted in the study. Several women had not directly witnessed infants being breastfed and therefore had not been given the opportunity to internally normalise it. Those who had directly witnessed it within their family were more likely to view it as the norm, as were those who knew they had been fed in this way as a child.

‘I think I always had it in my head, I know my mum breastfed all three of us, me, my brother and sister…just kind of thought that was the thing to do really.’

(B8)

‘I always thought I'd want to bottle feed, so that it wasn't until I became pregnant…I had no experience, I didn't know anybody else who had breastfed, so I had nothing to go against.’

(B9)

Family exposure did not always create a positive mindset, with participants in both groups identifying that breastfeeding was something to be tried but with a degree of resignation that it would be painful, problematic and short-lived. Many of the women in group A referred to formula products as ‘regular powder stuff’ (A1) and ‘normal milk’ (A4). Perceptions of bottle feeding as the more convenient method was high among group A and a commonly reported message from peers with children. Group B reported a tendency from their mothers, or partner's mothers to disapprove of exclusive breastfeeding beyond the early months. Overall, the participants expressed a positive attitude to breastfeeding, with most feeling that it was something they had, or wanted, to try.

‘I think they have done [friends have breastfed], but then they all seemed to go quite quickly onto the bottle. I think it just seemed more convenient for them or something. They're all quite young, so I think yes it was just more a convenience thing really.’

(A4)

‘I think that's just literally friends telling me…“when I put them onto bottle they slept better”.’

(A6)

‘Once T got past 6 months, it was really, really strange and they were coming out with things like “you're going to turn him gay”.’

(B6)

Privacy: ‘I wouldn't…want my husband looking at a bare breast whilst eating cucumber sandwiches’

The topic of feeding an infant in public was discussed by all participants with a focus on news-related debates surrounding the appropriateness of public breastfeeding in certain locations. There was a common feeling across both groups that breastfeeding in public was unusual. The language used showed that breasts were viewed as a sexual, private part of the body and this view was circulated within family and peer environments.

‘It takes your eye but then…I suppose it's natural… it's just a bit unusual when you see it.’

(A3)

‘One of my good friends…she didn't feel comfortable feeding her own daughter at her christening, which seemed ridiculous…it's definitely not the norm.’

(B6)

‘I personally wouldn't want some random bloke to get a glimpse of my breast in a café, that's scary… So, it's just that display of flesh isn't it? It's just it gets attention and actually to be honest I wouldn't necessarily want my husband looking at a bare breast whilst eating cucumber sandwiches either.’

(B7)

‘People don't feel comfortable getting their boobs out and breastfeeding in public generally.’

(B9)

‘[we need] more open attitudes to breastfeeding in our culture. I was very nervous to feed outside of the house with my first.’

(B30)

Women talked about portrayals of breastfeeding in public in the media, particularly social media campaigns, highlighting cases where a feeding mother's rights had been denied. The consensus feeling among the participants was that this news may have been creating an issue where there did not need to be one. Participants felt that the focus of both journalism and social media tended to be on extreme cases, either where breastfeeding in public had been refused or shunned or promoting prejudice against mothers who were bottle feeding in public.

‘…and media pressure to breastfeed, I would have been embarrassed feeding him a bottle in public.’

(B19)

‘…as a mother who express feeds, I am very aware of the media coverage, particularly Facebook coverage about breastfeeding…I feel ashamed to bottle feed my baby in public…I want people to know I'm using breastmilk.’

(B31)

Media as a double-edged sword: ‘social media is a nightmare’

Although most of the participants expressed a general lack of interest in news media generally, many mentioned frequent use of social media. A trend among group B appeared to be to seek out information relevant to breastfeeding through social media. These sites (mainly Mum's net, NetMums and National Childbirth Trust) seemed to provide an important source of support for breastfeeding mothers. Although these representations on social media suggest a useful role for media in promoting and maintaining breastfeeding behaviour, other representations were viewed as being unhelpfully divisive in the point they were trying to promote. This was highlighted with reference to breastfeeding in public, the ‘breast is best’ campaign and the benefits of formula feeding.

‘Most media stories are about women being thrown out of cafés for getting their boobs out.’

(A7)

‘I can't remember really seeing anything about breastfeeding, except that one about the place in London that threw out a woman for breastfeeding. Other than that I can only think about the formula adverts really.’

(A9)

‘I think a more positive approach from all social sources, the breast is best debate seems to currently be fuelled by media and particularly social media, it's damaging for both sides.’

(B14)

Most of the women felt that such extreme media representations were unrepresentative of actual behaviour, but several did express that a real experience could hold more influence than information about breastfeeding. While some participants in each group believed that articles offering statistical and financial information about the importance of breastfeeding would offer a largely positive influence on new mothers, around half the women expressed concern that reports of this nature created the impression that breastfeeding is being pushed as a money-saving exercise for the NHS, disconnected from the health implications. The accuracy of the statistics was also questioned by many of the participants.

‘You've got this government legislation persuading people “breast is best. You must breastfeed” but there's just such little support out there for making that happen…is this just about reducing NHS costs?’

(B22)

‘I've noticed a lot recently on social media about how important breastfeeding is and even some stuff about how formula can kill. I don't know much about it, but that doesn't seem right to me.’

(A8)

Participants highlighted how the nature of feeding discussions in parenting magazines and on social media created an air of pressure to breastfeed, mixed in with product advertisements, which were unhelpful and written in such a way that ‘if they can't breastfeed, it just makes them feel guilty’ (B3). This was further exacerbated by the lack of support (as noted above) for breastfeeding often present within the NHS.

‘From…media and other mums that there is an underlying shame attached to not [breastfeeding]. “Breast is best” but there needs to be more understanding about the reasons some women can't breastfeed: the unbearable pain and lack of supply being perfectly acceptable ones.’

(B18)

‘Social media is a nightmare. New mothers don't need the pressure. As long as baby is fed who really cares.’

(B20)

The profit-making aspects of the formula industry were referred to by many mothers in discussion of parenting magazines and formula advertising. They felt patronised by them and found a lack of reasonable feeding features.

‘I think every other page was an advert for a steriliser or a new bottle.’

(B3)

‘It was just like, “10 reasons why you'll want to breastfeed”, “10 reasons why you'll want to formula feed”… and it just treated me like I was just some stupid consumer…’

(B2)

Negative breastfeeding exposure: ‘they have bottles in the background and [are] asking each other to feed the baby’

Where exposure to breastfeeding had been lacking, several potential influencers in the media were discussed, in most cases reinforcing messages of breastfeeding as problematic or formula feeding as ‘convenient’.

Television advertising of formula appeared to be an important area of concern. The participants drew attention to the imagery used to create an impression that their product would be more convenient than breastfeeding.

‘Formula advertising and convenience is just the norm but people don't realise breastfeeding can be much more convenient.’

(B20)

‘I can picture the baby formula ads…it's kind of shown to help and have all these benefits to help their development and all of this. Yes, it's kind of shown like its equal to if you breastfed, you have the same benefits.’

(A2)

‘I see that they say about how the best milk you can have is…mother's milk…and then they say just about what's in their nice formula and how it helps your child grow and fulfil their potential… the formula companies do tend to use the moving on kind of rhetoric to make you feel like there comes a natural point where it is wrong to carry on breastfeeding and it is right to move on to other stuff.’

(B2)

When discussing wider forms of media representation, all participants stated that they had seen very little reference to how a baby is fed when they are shown on television or film. In soap operas, it was apparent that while they feature a lot of infants being born, the participants reported that ‘they have bottles in the background and [are] asking each other to feed the baby’ (A1). While this is something that may not be overtly apparent to viewers, the presence of bottles and seeing mothers asking others to feed their children in this manner serves to subtly perpetuate the normative view of bottle feeding in a television scenario designed to resemble real life situations (albeit, highly exaggerated ones).

‘Joey was there, and he found [breastfeeding] quite arousing…like showing how women are all fine and it doesn't bother them, whereas men are a bit like “whoa okay your boobs out”.’

(A5, referring to an episode of ‘Friends’)

Aside from soap operas, fictional representations of or reference to breastfeeding recalled by participants surrounded comedic sketches of sexualised image of breasts, extreme extended breastfeeding (of an adult male) and situations that would potentially fuel the perception that breastfeeding is not taken seriously.

‘I watched a film recently where the mum, the breasts got way too big and they were full…she couldn't breastfeed…and then there was a whole comedy scene based on the fact that they were like basically going to explode…It was quite a graphic scene as well, it's quite shocking.’

(A2, referring to the film ‘Bad Neighbours’)

Factual programmes of breastfeeding that were recalled tended to be of a shocking nature, such as those showing footage of much older children breastfeeding. This gave the impression of breastfeeding as something ‘disturbing in a way, because you don't really see it going on that long’ (A2). The prevalence of this type of story appeared to create a level of support to many of the participants' preconceived ideas that infants should only be breastfed for very short durations, in case it becomes perceived as strange or unacceptable by others.

‘…the woman with the very large child off her dangly breast. She was kind of really adamant about all the health effects for her, but not so much what the benefits for the child were…I do wonder whether it's to do with the mum not letting go or not letting go of that closeness, not allowing the child to be independent.’

(B7)

‘I remember watching a documentary about…sort of extended feeding and all the women on it just seemed like totally bonkers. Now I know a lot of people that do extended feeding and they're really normal, it was like why couldn't you have just used them?’

(B6)

Planned behaviour versus experience: ‘by the time I had seen her, she'd already had several syringes of formula’

Every participant highlighted the fact that breastfeeding had not come as naturally or easily to them as they had anticipated before giving birth. Efforts from midwives during pregnancy to emphasise the health benefits to the child were expected, but the women frequently reported that, in hindsight, a great deal of information concerning the realities of lactation were omitted at this stage and left them feeling unprepared for common difficulties. This often high-pressure approach from midwives to breastfeed, however, was universally mismatched with appropriate levels of support, training and availability after their children had been born. Participants highlighted the lack of support for breastfeeding within the NHS.

‘You've got this government legislation persuading people “breast is best. You must breastfeed” but there's just such little support out there for making that happen.’

(B22)

‘…practice with knitted boobs and dolls and stuff… it just felt very divorced from reality, and I don't really remember much practical advice from antenatal class…they just spouted the mantra “breast is best” and didn't address any of the problems that you could come across with breastfeeding.’

(B28)

In these situations, the participants' generally negative experiences meant that they had been unable to initiate, or continue, breastfeeding. Two participants reported that formula was so readily available while in hospital immediately post-birth that it was provided possibly as a convenience for the health professionals themselves, who did not offer new mothers adequate support and time in assisting breastfeeding. One mother stated that her child was given formula before she was given the chance to learn how to express her own milk. Another participant recalled a conversation where a midwife openly expressed relief that no assistance with feeding was required as this was perceived as a nuisance. This contributed to reports that it was easier to start using formula than make further attempts to breastfeed their children.

‘By the time I had seen her, she'd already had several syringes of formula…No one approached me and said “do you want to try and express”, I was just left [for] 9 hours.’

(B10)

‘The midwife would come over and I'd be breastfeeding fine and they would be so pleased, they'd be like “oh gosh you know some mums…oh! I have to see them all the time to help them breastfeed”.’

(B2)

‘So I tried feeding him and then she came in and then she grabbed him and she twisted his head and pushed him on to me really hard…I rung the bell again and eventually she came in and she said “oh you again”.’

(B5)

‘It was absolutely gutting, like I failed as a human being by not being able to feed him properly. I was made to feel that way…I just didn't know what I was doing wrong and she was just terrifying and I couldn't ask her for help because she frightened me so much.’

(B1)

Discussion

This study has identified that breastfeeding is not necessarily seen as the normative method of feeding an infant, particularly after the first few months, within the UK. The ‘breast is best’ campaign emphasises the importance of exclusively breastfeeding for the first six months of an infant's life, followed by the introduction of nutritional foods alongside breastfeeding up to, and beyond two years of age (WHO, 2011). Yet, figures are showing little improvement across the UK (Nicholson and Hayward, 2021). Initial views on breastfeeding before pregnancy were formed by an individual's prior experience and exposure to breastfeeding behaviour, either through their own social exposure or the media. Positive perceptions of breastfeeding before pregnancy and birth were espoused as a prime reason for commencing breastfeeding postpartum. Participants' inner social circle was the main influence, including an awareness of how they were fed themselves as infants and the experiences of their mothers and other close family and friends. Those with familial experiences of breastfeeding were more likely to initiate breastfeeding behaviour, and more inclined to persevere with breastfeeding when problems presented. The importance of exposure to breastfeeding in creating a normalised attitude has been highlighted in previous research (Ogbuanu et al, 2009). In the present study, those with less exposure relied more heavily on the media to form their understanding of breastfeeding.

The findings support previous literature highlighting the importance of family support in initiating and persevering with breastfeeding (Rempel and Rempel, 2011; Maycock et al, 2013), but that this support alone is not enough to ensure successful maintenance (Rempel and Rempel, 2011). Appropriate support from healthcare professionals is an integral element to maintaining behaviour (Keevash et al, 2018).

The findings from the present study show a clear role for mainstream media, advertising and social media in influencing women's preconceptions of breastfeeding. Participants in this study supported the findings of previous research suggesting that British media coverage of breastfeeding tends to be relatively sparse (Henderson et al, 2000). Although many participants in this study were less concerned with direct media coverage relating to breastfeeding, subtle messages such as babies on soap operas being shown with bottles while mothers continued life as normal serve to perpetuate their notions that breastfeeding is inconvenient. This supports previous research by Henderson et al (2000) that identified a distinct lack of breastfeeding representation throughout British media. The advertising of formula products was found to add to this, with imagery conveying an idea that their product is more convenient and of similar nutritional composition to breastmilk. Adhering to national legislation (Legislation.gov.uk, 2007), advertising is limited to formula intended for children over the age of 6 months with specific rules on what advertisers can and cannot include. These rules are often violated with minimal consequences for companies (Hastings et al, 2020). Breastfeeding is also shown to be outside of the norm through its use in comedic contexts with reference to sexualised attitudes towards breasts, uncomfortable perspectives on extended breastfeeding and the painful and messy aspects of breastfeeding itself. Influences such as these may have appeared trivial on the surface to the participants but combine to perpetuate the notion of breastfeeding as an unusual act.

Limitations

The study allowed participants to openly discuss issues of breastfeeding, both positive and negative, within the context of sociocultural influences on perceptions and behaviour. The study was designed using a qualitative approach in order to better understand the experiences of women who have breastfed and the influences on those who have yet to breastfeed. While this allowed for rich detail data collection, the study cannot necessarily be extrapolated to a wider population of women who breastfeed or to those who may breastfeed in the future. It is important to note that the nature of the sampling meant that the participants did not represent a broad socioeconomic range and were not ethnically diverse. Therefore, the experiences of those from more deprived parts of the UK were not represented.

Implications for practice and policy

While efforts are being made to increase breastfeeding rates through campaigns, such as the exclusive feeding initiatives introduced by WHO (2011), rates in the UK are still very low (Shortis, 2019). As such many young women within the UK are unlikely to have direct experience of breastfeeding, which in turn is likely to perpetuate low rates. A possible solution to this is increased public exposure to breastfeeding through public health initiatives to raise the profile of ‘normal and healthy’ breastfeeding. Sadly, this study also identified a continuing concern among many women about breastfeeding in public, despite legislation to protect their rights that participants seemed largely unaware of (Equality Act 2010). Coupled with unhelpful and negative media portrayals of breastfeeding and a continued representation of bottle feeding as the ‘norm’, this means that young women in the UK are still not being exposed to the positive breastfeeding experiences that may promote breastfeeding self-efficacy, despite some improvement in media portrayals over the last decade (O'Brien et al, 2017). Additionally, training for staff in public places needs to be improved to ensure the rights of those who wish to breastfeed in public. This in turn would increase the prevalence of public breastfeeding and make the behaviour more normative and visible among younger women.

These elements, in conjunction with the identified lack of support from healthcare professionals, would seem to come together to create a ‘perfect storm’ to prevent women in the UK from initiating or continuing with breastfeeding long term. Therefore, greater support is needed among healthcare professionals to ensure mothers have the help they require to successfully breastfeed by renewed commitment to the baby friendly initiative programmes currently run across the UK. Alongside more information of the process of breastfeeding and how to overcome difficulties provided in the antenatal period, this may reduce the cessation rate currently seen in the UK (Keevash et al, 2018). There need to be wider discussions within NHS services about how time pressures and lack of funding within services are influencing a reduction of breastfeeding initiation and ability to breastfeeding longer term (Keevash et al, 2018). Another aspect of practice improvement should be to consider carefully wording public health campaigns such as ‘breast is best’, which while well-meaning, can lead to a greater sense of pressure and guilt among mothers who struggle to breastfeed (Keevash et al, 2018). Improvements need to be made to antenatal services to ensure there are adequate resources to provide vital information about breastfeeding to promote realistically to women to encourage them to opt for breastfeeding before birth (Keevash et al, 2018)

Conclusions

This study aimed to explore the influences of media, particularly social media, on women's perceptions of and intentions to breastfeed. The study identified that a lack of positive portrayals of breastfeeding in a range of contexts, including the family, in public and through the media, often leaves young women with a negative view of breastfeeding as a normative behaviour. Exposure to negative media representations of breastfeeding and divisive social media campaigns, coupled with poor support from healthcare professionals were identified as key influences in preventing long-term breastfeeding behaviour. Future public health campaigns need to focus on promoting a more positive, yet balanced perspective on breastfeeding, alongside greater attention to mainstream media and social media portrayals of breastfeeding. Greater emphasis should also be placed on ensuring formula advertising within the UK is mediated by greater positive representations of breastfeeding.

Key points

- This ethnographic study interviewed 40 women on sociocultural influences on breastfeeding perceptions and behaviour.

- Participants reported that exposure to those who are breastfeeding helps to encourage breastfeeding in others.

- Breastfeeding in public is still viewed as a difficult aspect that mothers need support with.

- Social media can play an important role in supporting breastfeeding but can also lead to difficulties for those mothers who are struggling to breastfeed.

- There needs to be tighter regulation around the way breastfeeding is portrayed in the general media, such as in soap operas, that have the power to influence the perceptions of the general public.

CPD reflective questions

- What norms and views around breastfeeding could health professionals address with pregnant mothers?

- How can midwives provide information during the antenatal period to normalise breastfeeding behaviour?

- How might professionals discuss media representations with pregnant mothers?

- How could legislation be improved to reduce the biases in British media portrayals of breastfeeding?

- How can we support mothers to navigate social media in a supportive way?