Planning where to give birth is arguably one of the most significant choices that a woman will make during her pregnancy. Yet for many women, an assumption is made that birth will take place in a hospital setting. Maternity care in Britain has changed significantly throughout the years: in 1960, just over 60% of births took place in a hospital setting, while this figure rose to 96% by 1990 (Johanson et al, 2002).

The Peel Report (Standing Maternity and Midwifery Advisory Committee, 1970), which recommended that the safest place for women to give birth was in consultant-led maternity units, resulted in the majority of births taking place in these settings. Recent figures show that only 13% of births take place outside of hospital units (National Audit Office (NAO), 2013). The publication of the birthplace study by Brocklehurst et al (2011) challenged the assumption that hospital was the safest place for mother and baby. The findings endorsed a policy of choice that has been in place since 1993 when Changing Childbirth was first published (Department of Health, 1993).

Following on from Changing Childbirth (Department of Health, 1993), the Better Births report (National Maternity Review, 2016) recognised that although improvements had been made in maternity services, many women still reported not being offered a real choice in the services available to them.

One local free-standing midwifery unit responded to the recommendations of the Better Births report by creating a workshop for low-risk women to attend. The workshop was aimed at overcoming the barriers faced in birthplace discussions with women. The workshop encouraged group discussion surrounding place of birth and discussed the benefits and potential challenges of each birthplace option available. The findings of Brocklehurst et al (2011) were discussed and a tour of the birthing unit was completed. The overall aim of the workshop was to increase women's knowledge of their choice of birthplace options. An audit of the workshop was proposed to assess its effectiveness and recognise any developments that could be made.

Literature review

There is much research that focuses on interventions to enable discussions and increase women's knowledge of their birthplace options. Some of these interventions have included information leaflets for health professionals (Kirkham et al, 2001), educational initiatives targeted at women (Barber et al, 2006a) and a birthplace app to aid women's decision-making (Walton et al, 2014). Little evidence was shown to demonstrate the effectiveness of leaflets (Kirkham et al, 2001; Barber et al, 2006a) and although the midwives found the birthplace app a useful communication tool (Walton et al, 2014), it did not show any effect on birthplace choices. Henshall et al (2016) conducted a systematic review of the research into interventions to aid birthplace discussions. They found that many of the studies lacked precision and detail when reporting their findings and showed a lack of rigour in their data analysis techniques. Four studies were found to have a high risk of bias (Barber et al, 2006b; Davis and Walker, 2010; Royal College of Midwives (RCM), 2011; Vedam et al, 2012) and concerns were raised about the generalisability of the findings. Overall, the researchers felt that studies failed to demonstrate the effectiveness of interventions that supported midwives to discuss place of birth with women.

Rogers et al (2015) noted that many midwives were unaware of the findings of Brocklehurst et al's (2011) birthplace study, and were therefore unable to disseminate the information it contained to women. Several studies have also found that midwives lacked confidence in discussing birthplace options (Jomeen, 2007; Henshall et al, 2016; Coxon et al, 2017). Midwives have been shown to feel affected by their own negative experiences (Houghton et al, 2008) and to be risk-focused, fearing blame if the birthplace choice cannot be fulfilled (Madi and Crow, 2003).

Women described receiving a lack of clear information surrounding place of birth (Barber et al, 2006a; Jomeen, 2007), with some women reporting that health professionals not only gave sparse information, but were actually obstructive to choices (Coxon et al, 2017). Most discussions took place at the beginning of pregnancy and women felt unprepared to make such choices (Jomeen, 2007; Coxon et al, 2017). Since the publication of Brocklehurst et al's (2011) birthplace study, strategies should be implemented to disseminate the findings to women, as midwives now have the evidence to support the discussion of birthplace options.

Methods

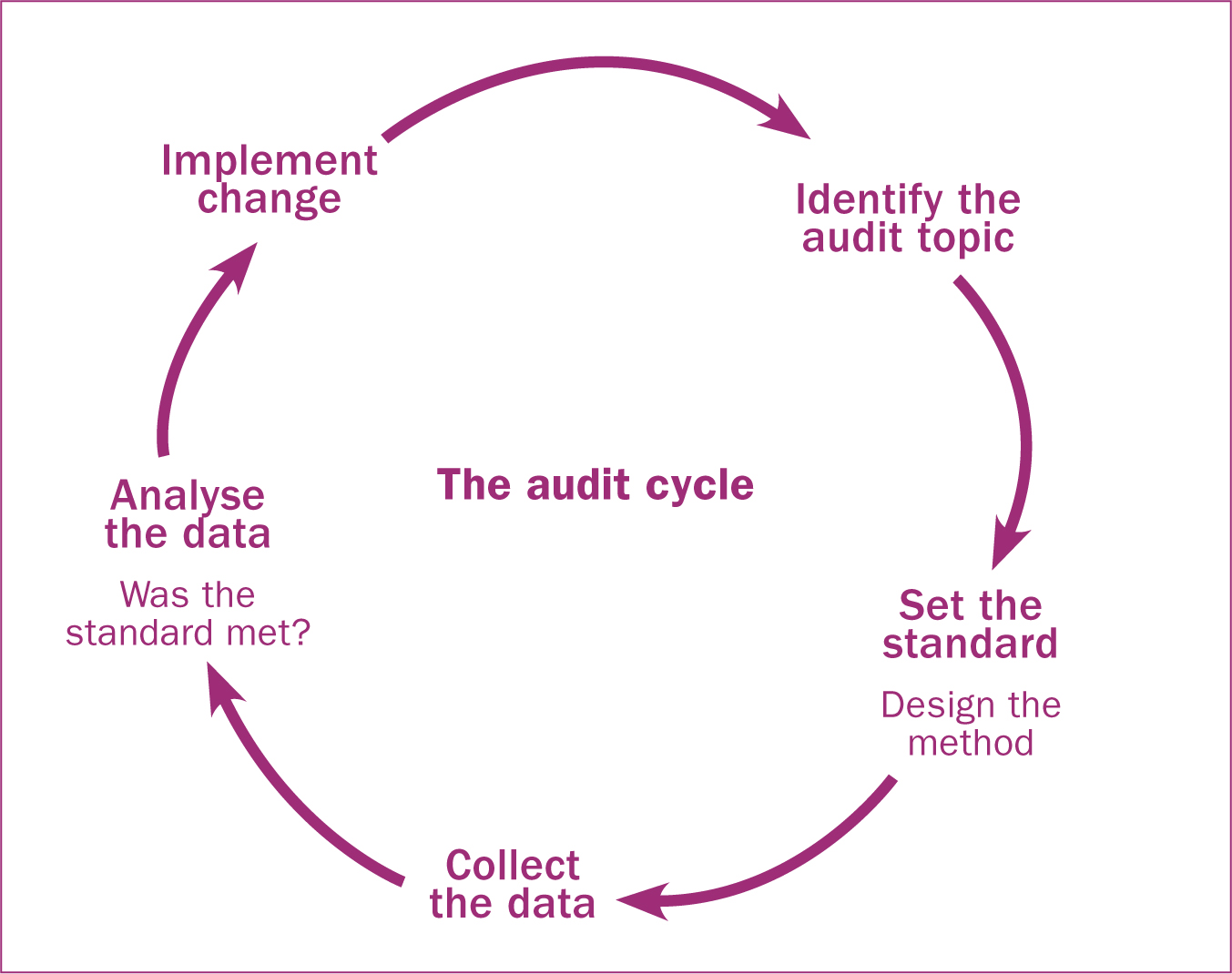

Clinical governance is integral to ensuring excellence in care. It is a process of continuous quality improvement with clinical audit at its heart (National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE), 2002). As the literature shows, women report not receiving adequate information surrounding birthplace options. One local area attempted to address this by creating a workshop where information on birthplace choices could be delivered to a group of women and their families. A clinical audit of this workshop was proposed within a structural framework known as the audit cycle (Figure 1). As the workshop was being piloted in one area of the Trust, an initial audit was proposed, with a potential for future research in the area. The aim of the audit was to evaluate the effectiveness of the workshop and its implementation, with the eventual goal of improving service quality for women.

The audit topic

The aim of the workshop was to promote and encourage discussions of birthplace options, which included disseminating the findings of Brocklehurst et al's (2011) birthplace study. Local data was also incorporated, with figures on transfer rates and times. The workshop was run by the same experienced midwife to promote standardisation of the information. Midwives booked women to attend the workshop at approximately 28 weeks' gestation. It was felt that this was an appropriate point for women to attend the workshop as they would have already received a great deal of other information at the booking appointment. No evidence could be found to recommend the most appropriate gestation for birthplace discussions.

Women who qualified for the Trust's low-risk pathway of care were booked to attend a workshop by their midwife. Women not on this care pathway were encouraged to give birth in a consultant-led unit.

Setting the standards

The workshop was piloted in one local community area with a freestanding midwifery unit. The midwifery team comprised eight midwives who provided antenatal and postnatal care in a caseloading model. They also provided on-call cover for all intrapartum care for women booked to give birth at the midwifery unit. Women were encouraged to bring someone with them to the workshop, as research shows that a woman's partner and her family have a significant influence on birthplace decisions (Ogden et al, 1998; Andrews, 2004; Borrelli et al, 2017). As the workshop was still in its infancy and not all low-risk women (such as non-English speakers) would benefit, the standard for attendance was set at 70%. The birth rates in the unit were also monitored to note any alteration or significant change in the number of births following the introduction of the workshop.

All women who attended the workshop within a 6-month period were audited against set standards to eliminate the possibility of selection bias.

Ethical approval

As this was as clinical audit, not original research, full ethical approval was not required. However the authors did obtain agreement from the Trust to conduct the audit and to use any relevant data.

Data collection

Data for the audit was collected manually from antenatal clinic diaries. It was difficult to quantify the exact number of low-risk women who were cared for during the 6-month period as there were a range of due dates, with some women becoming higher-risk due to health concerns. It was decided that all women who reached 28 weeks of pregnancy during the time period and who were low-risk at the time of data collection would be included. A questionnaire was devised and handed out to every woman to complete at the end of the workshop. They were asked to circle ‘yes’ or ‘no’ to if they felt they had gained adequate information about their birthplace options. The women were not asked to disclose their birthplace choice directly after the workshop, as it was felt that this could make the women feel pressurised and that it would also not allow them time to digest the information and discuss with their family.

The data collected is shown in Table 1, which shows the number of women, and Table 2, which shows the comparison of the standards.

| Low-risk women who reached 28 weeks (n) | Women who were booked to attended the workshop (n) | Women who attended the workshop (n) |

|---|---|---|

| 118 | 54 | 42 |

| Standard | Target (%) | Result (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Low-risk women are being booked to attend the workshop | 70.0 | 45.7 |

| The women booked to attend actually go | 100.0 | 77.7 |

| The women who attend report receiving adequate information | 100.0 | 100.0 |

The birth rate of the birth centre was also noted, both before the start of the workshop and after. In the 12 months before the workshop, there were 64 births in the birth centre. In the 12 months following the implementation of the workshop, 84 births took place, an increase of 31.3%.

Analysing the data

Of the three standards, only one reached the target criteria. It is clear that the women who did attend the workshop felt that they received adequate information on birthplace options. The information given was centralised and delivered by one midwife, who was experienced in all birthplace options. Midwives are the health professionals with the biggest impact on choice of birthplace (Barber et al, 2006a: Barber et al, 2006b: Houghton et al, 2008); however many are affected by their own negative experiences and lack of confidence in discussions with women (Houghton et al, 2008; Rogers et al, 2015). Having a single midwife who was confident in leading the workshops eliminated these issues.

It is clear that the workshop delivered its aims and that women felt informed of their options after attending. However attendance was poor, with only 45.7% of eligible women being booked by midwives. As Moore et al (2014) have stated, change is a complex process. The workshop was in its infancy and with this being the first audit to assess its efficacy, challenges were expected. One option to increase attendance is to have all of the midwives in the team lead the workshop.

A team should be encouraged to establish a vision and strategy and allow them to lead change (Kotter and Cohen, 2002). If the midwives were involved in informing and delivering the workshop, it would allow them to take more ownership. This may also influence them to increase the number of women whom they book to attend. In addition, educating all of the midwives would give them the skills to have the discussions on a one-to-one basis. This would give them the confidence to have a conversation about birthplace options with women who were not eligible to attend the workshop.

Another option to increase attendance is to have the workshop as a default option. Rather than opt in, the midwife would book the woman to attend a workshop at the 16 week appointment unless the woman declined. As Halpern et al (2007) describe, the benefit of default options is that they influence decisions without restricting choice. Opt-out models can help to avoid well-described pitfalls of human decision-making, such as status quo bias, by addressing this aversion to change and a fear of choosing the wrong option (error of commission) (Halpern et al, 2007; Desmond et al, 2013).

The number of births in the unit increased significantly in the 12 months after the implementation of the birthplace workshop. Although it cannot be proven that this increase was caused solely by the workshop, the 31.3% increase does imply some merit and efficacy of the workshop.

Discussion

The discourse of choice is now an accepted part of maternity care. In spite of this, women widely report receiving a lack of information on birthplace options. Many strategies to increase out-of-hospital births have been implemented nationally and internationally (Hadjigeorgiou et al, 2012; Rogers et al, 2015; Coxon et al, 2017). These interventions include leaflets, strategies to increase midwives' knowledge, and a decision aid to help women make an informed choice. These studies showed varying degrees of success and it is clear that more research is required in this area. This calls for more structured and consistent approaches to be adopted for the provision of information to women (Henshall et al, 2016; Coxon et al, 2017).

The results of the audit clearly show that a birthplace workshop was a valuable tool to educate women about their choices. The noteworthy increase in births after its implementation also cannot be ignored. Although attendance could be improved, the women who did attend reported that they felt better informed in their decision-making. Historically, time pressures have been reported by midwives as a barrier to individual discussions with women (Henshall et al, 2016), so delivering the information in a group setting addresses the issue of time constraints. With the changes recommended, the authors are confident that a re-audit would show an increase in attendance.

Local initiatives, such as this workshop, must be commended. Although the workshop has been shown to be very effective, it cannot alleviate all the issues that affect choice. With 45% of women in the UK purported to be low-risk at the time of birth (Sandall, 2013) and only 13% of births occurring outside obstetric units (NAO, 2013), it is clear that more needs to be done on a national level. It is noted that most research was conducted before the publication of the birthplace study (Brocklehurst et al, 2011) so health professionals did not have much robust evidence to support discussions with women. Nevertheless, Coxon et al (2017) found in their review of articles between 1992 and 2015 that very little had changed in that time period. When Hannah et al (2000) showed a less favourable outcome for breech babies delivered vaginally rather than by caesarean section, it resulted in an immediate change to guidelines on breech births. The birthplace study (Brocklehurst et al, 2011) was hoped to have a similar effect on birthplace choices. Such a large study with clear outcomes indicating the safety of out of hospital births was expected to cause a cultural shift, but data showed a decrease in homebirths after the publication, from 2.4% in 2011 to 2.3% in 2012 (NAO, 2013).

The view of hospital birth as the norm is deeply entrenched, not just in medical discourse but also in the wider social context (Jomeen, 2007). After the publication of the birthplace study (Brocklehurst et al, 2011), media coverage focused on the risks of homebirth for first-time mothers and appeared to ignore the other groundbreaking findings of the study (Jeffreys, 2011). The media appears to influence women's decision-making by dramatically portraying medicalised births and neglecting to show normal births (Luce et al, 2016). In this technological era, the effect of the media must not be underestimated in its power to influence childbearing women.

Although hospital is still considered the safest option for childbirth, research shows that even when a woman chooses to give birth in an obstetric unit, they still wish to have a natural birth with care from a midwife, and only have obstetric input should complications arise (Houghton et al, 2008; Borelli et al, 2017). This demonstrates that women instinctively choose a low-risk pathway but are affected by perceived risk. Tensions between women's perception of risk and their notions of birth as normal and natural are inherent, and it is the responsibility of health professionals to guide and educate women through this decision-making process so that they have confidence in making an informed choice.

As midwives are the professionals with the most influence in a woman's birthplace decision (Barber et al, 2006a), strategies must be implemented on a national level to guide birthplace discussions. Focus must be directed towards ongoing midwifery education and allowing newly qualified midwives opportunities to gain experience with out-of-hospital births (Rogers et al, 2015; Coxon et al, 2017). The importance of creating appropriate models of care to enable midwives to increase their skills and confidence in different birth settings cannot be underestimated (McCourt et al, 2012). If the barriers to change are to be overcome, initiatives such as the workshop audited here must be supported by a national campaign. It is not acceptable that women are not benefiting from the research that supports out-of-hospital births.

Conclusion

The publication of Changing Childbirth (Department of Health, 1993) brought hope that true choice could be given to childbearing women by giving them adequate information about the services and options available. Before the publication of Changing Childbirth, recommendations for place of birth favoured institutional births. The Better Births report (National Maternity Review, 2016) showed that very little had changed and reflected that women were still not being offered adequate information.

Although results of the audit showed poor attendance, the workshop is still in its infancy and new initiatives take time to become established. Of the women who did attend, 100% reported feeling they had received adequate information surrounding their birthplace choices. The authors are confident that a re-audit after the implementation of the proposed changes would show an increase in the standards.

Local initiatives such as the workshop should be celebrated but what is needed is national momentum to alter the status quo and challenge the deeply entrenched belief that hospital is the safest place to give birth.