Approximately one-third of women appraise their birth as a traumatic experience (Ayers et al, 2016) and the prevalence of experiencing a traumatic birth are suggested to have increased for women giving birth during the COVID-19 pandemic (Mayopoulos et al, 2021). There are many factors that contribute to a traumatic childbirth experience, but a woman's subjective perception of birth is consistently a stronger predictor of trauma than her obstetric experience (Czarnocka and Slade, 2000; Söderquist et al, 2006; Dekel et al, 2017). In this sense, birth trauma is regarded as being ‘in the eye of the beholder’, as a mother's traumatic birth experience may be viewed as routine practice by healthcare practitioners (Beck, 2004). Because of this, women who experience a traumatic birth often report that they have not voiced their distress through fears that their concerns would be dismissed (Moyzakitis, 2004). A woman's perception of their childbirth experience is significant to their postnatal mental health. A woman's appraisal of her birth is one of the most influential factors for developing symptoms of postnatal post-traumatic stress disorder (Beck, 2004). From the wider literature on post-traumatic stress disorder, it is known that a negative appraisal of a trauma event can evoke a current sense of threat and motivate avoidance behaviours that can perpetuate post-traumatic stress disorder symptoms (Ehlers and Clark, 2000). Therefore, in order for maternity care to provide early and effective support, it is imperative that research focuses on women's unique appraisals of their birth experiences to identify characteristics of birth that may cause women to reflect on childbirth as a traumatic or non-traumatic event.

Qualitative research surrounding birth trauma typically focuses on women who develop postnatal post-traumatic stress disorder or experience postnatal difficulties (Ayers, 2007; Coates et al, 2014; Peeler et al, 2018), or present findings only from women who experienced traumatic childbirth (Beck, 2006; Harris and Ayers, 2012; Hollander et al, 2017). A gap in the literature remains regarding qualitative comparisons of women's traumatic and non-traumatic birth experiences, irrespective of postnatal post-traumatic stress disorder presentation. This study examines and compares the subjective characteristics of birth in a non-clinical sample of women who described their birth as traumatic or non-traumatic. This study has two aims: to explore perinatal factors that contribute to women's appraisal of their childbirth experience and to explore differences in the subjective experience of childbirth between women who appraise birth as traumatic and women who appraise birth as non-traumatic.

Methods

Design

This qualitative study explores factors that contribute to women's appraisals of traumatic and non-traumatic birth experiences through semi-structured interviews. Women in the postpartum period were invited to recount their experiences during labour, birth and immediately postpartum. A qualitative study design with semi-structured interview questions was chosen to construct a contextualised understanding of women's birth experiences (Polit and Beck, 2010) and capture participant's unique perspective of their most recent birth.

Participants and recruitment

A subsample of 14 women taking part in a separate longitudinal study conducted by the first and third author were invited to participate in the present study using criterion sampling based on women's reports of their most recent birth experience as traumatic or not traumatic. Women were recruited for the present study through social media. Half of the participant sample interviewed reported their most recent birth to have been a traumatic experience (n=7) and half reported that it had been non-traumatic (n=7). Women completed interviews between 3–5 months postpartum (mean=3.7 months).

Data collection

Data were collected via semi-structured interviews. The interview schedule was developed based on previous comparative work by Ayers (2007) but questions were phrased neutrally to explore factors contributing to a traumatic or non-traumatic childbirth experience. Interviews were conducted over the phone between February and April 2020 and all interviews were digitally recorded. Prior to the interview, women were asked to complete an online survey containing questions relating to demographic information, birth characteristics and a postnatal trauma symptom scale, the City Birth Trauma Scale (Ayers et al, 2018). These data are shown in Table 1.

Table 1. Sample characteristics from demographic information, mode of delivery and trauma symptom scores at 3 months postpartum (n=14)

| Number | Age (years) | Ethnicity | Relationship | Parity | Delivery mode* | Trauma symptom score† | Appraisal |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 01 | 30–35 | Mixed race | Married/cohabiting | Primiparous | Emergency caesarean section | 7 | Traumatic |

| 02 | 36–41 | White | Married/cohabiting | Primiparous | Planned caesarean section | 3 | Traumatic |

| 03 | 24–29 | White | Not living with partner | Multiparous | Normal vaginal delivery | 32 | Traumatic |

| 04 | 36–41 | White | Married/cohabiting | Multiparous | Planned caesarean section | 30 | Traumatic |

| 05 | 36–41 | White | Married/cohabiting | Multiparous | Emergency caesarean section | 30 | Traumatic |

| 06 | 36–41 | White | Married/cohabiting | Multiparous | Planned caesarean section | 1 | Traumatic |

| 07 | 24–29 | White | Married/cohabiting | Primiparous | Forceps delivery | 20 | Traumatic |

| 08 | 30–35 | White | Married/cohabiting | Multiparous | Normal vaginal delivery | 14 | Non-traumatic |

| 09 | 30–35 | White | Married/cohabiting | Primiparous | Forceps delivery | 2 | Non-traumatic |

| 10 | 30–35 | White | Married/cohabiting | Primiparous | Emergency caesarean section | 6 | Non-traumatic |

| 11 | 30–35 | White | Married/cohabiting | Primiparous | Normal vaginal delivery | 6 | Non-traumatic |

| 12 | 24–29 | White | Married/cohabiting | Multiparous | Normal vaginal delivery | 0 | Non-traumatic |

| 13 | 36–41 | White | Married/cohabiting | Primiparous | Normal spontaneous vaginal delivery | 3 | Non-traumatic |

| 14 | 30–35 | Other | Married/cohabiting | Primiparous | Normal spontaneous vaginal delivery | 8 | Non-traumatic |

Symptom score is out of 60 points, based on City Birth Trauma Scale

Data analysis

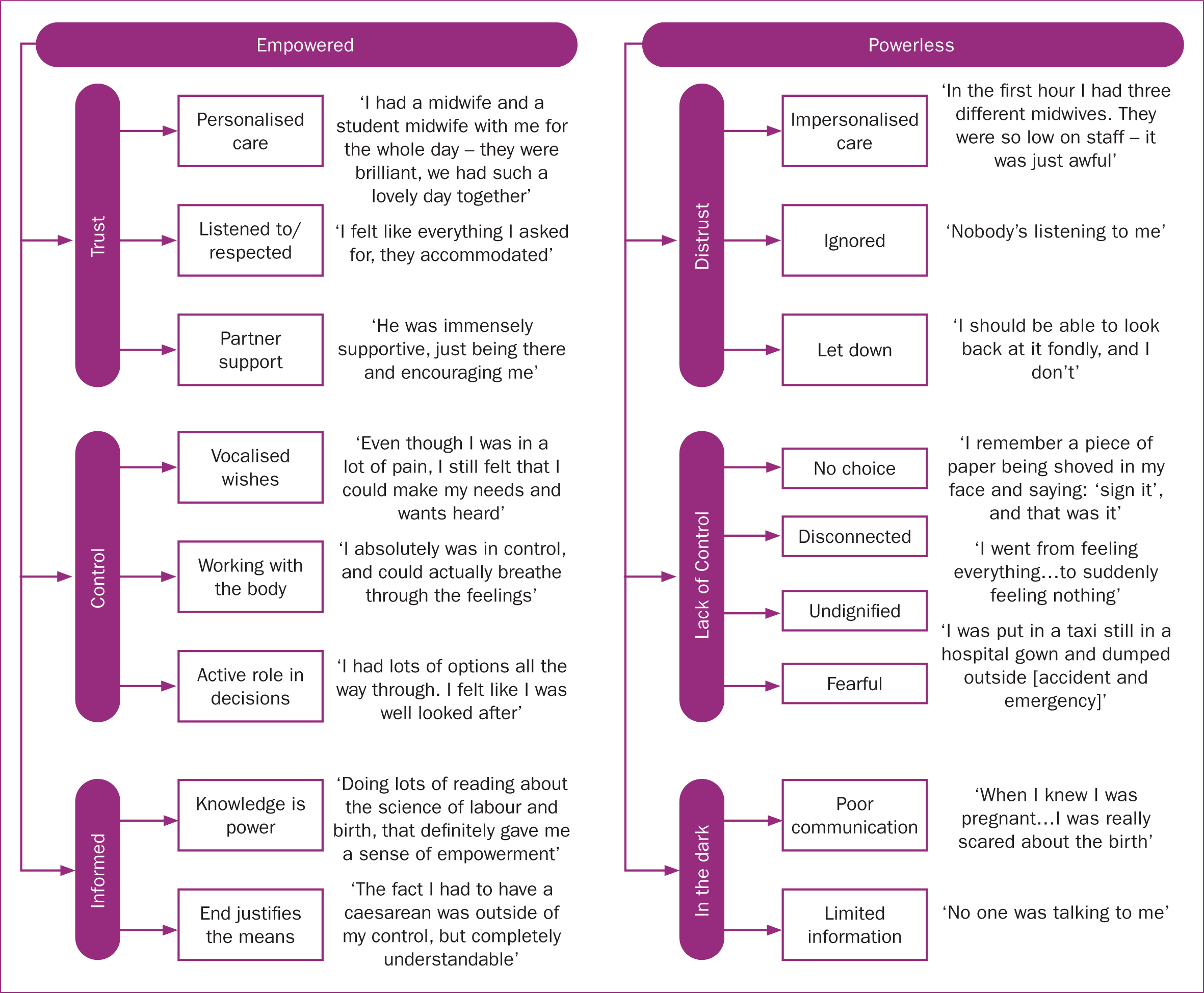

Interviews were analysed using thematic analysis following the six-step approach outlined by Braun and Clarke (2006) as an interpretative phenomenological approach to assess themes associated with women's appraisal of childbirth. Since the aim of this study was to examine how women's subjective birth experiences differ between childbirth appraised as traumatic and non-traumatic, themes were first extracted from all participant interviews with differences between the two groups noted and a thematic map generated (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Thematic map of overarching categories, themes and subthemes for traumatic and non-traumatic birth experiences

Figure 1. Thematic map of overarching categories, themes and subthemes for traumatic and non-traumatic birth experiences

Ethical considerations

Ethical approval was obtained from the University of Plymouth Faculty of Health Ethics Committee (Reference number: 18/19-1038). A participant information sheet and consent form were emailed to participants and both digital and verbal consent were obtained prior to interviews. All interviews were transcribed anonymously and all identifiable information was removed from transcriptions.

Results

Thematic analysis was conducted to identify factors that contribute to women's traumatic or non-traumatic appraisals of birth. It is important to acknowledge that a greater proportion of women who found birth traumatic experienced an assisted delivery. As the present study aimed to document women's subjective experience of birth, level of obstetric intervention was not further analysed. Nevertheless, this discrepancy should be kept in mind when drawing comparisons from themes of women's traumatic and non-traumatic appraisals. Thematic analysis revealed six main themes within two overarching categories relating to whether the mother felt ‘empowered’ or ‘powerless’ during and immediately after birth. Table 2 presents the main themes and subthemes identified between groups and Figure 1 presents the main themes and subthemes separated by category.

Table 2. Themes from interviews

| Themes | Subthemes | Predominant group of women who reported subtheme |

|---|---|---|

| Empowered | ||

| Trust | Personalised care | Women who appraised birth as non-traumatic |

| Listened to and respected | Women who appraised birth as non-traumatic | |

| Partner support | All women | |

| Control | Vocalised needs/wishes | Women who appraised birth as non-traumatic |

| Working with the body | Women who appraised birth as non-traumatic | |

| Active role in decisions made | Women who appraised birth as non-traumatic | |

| Informed | Knowledge is power | Women who appraised birth as non-traumatic |

| End justifies the means | Women who appraised birth as non-traumatic | |

| Powerless | ||

| Distrust | Impersonalised care | Women who appraised birth as traumatic |

| Ignored | Women who appraised birth as traumatic | |

| let down | Women who appraised birth as traumatic | |

| Lacked control | No choice | Women who appraised birth as traumatic |

| Disconnected | Women who appraised birth as traumatic | |

| Undignified | Women who appraised birth as traumatic | |

| Fearful | Women who appraised birth as traumatic | |

| In the dark | Poor communication | Women who appraised birth as traumatic |

| Limited antenatal or postnatal information | All women |

Empowered

The themes within the overarching category ‘empowered’ reflect participants' perception of feeling empowered during labour and birth and emerged predominantly from interviews with women who appraised birth as non-traumatic. These themes were ‘trust’, ‘control’ and ‘informed’. A subtheme pertaining to partner support was identified in interviews with all women, regardless of whether they viewed their birth as traumatic or not.

Trust: ‘I was quite happy to put it in their hands’

The first theme, trust, describes participants' expressions of trust in the support received from healthcare professionals and partners during labour and birth. Women who appraised birth as non-traumatic described the care they received as personalised, attentive, intuitive and consistent, reflecting a relationship of trust between the mother and the people around her. Women discussed feeling listened to and that their wishes were respected by healthcare professionals through being involved in discussions and treated with dignity in cases where obstetric interventions were required.

‘[The midwife] said the right thing…she just seemed to read me really well, and she was encouraging when I needed her to be and stepped back when I wanted her to as well.’

Participant 14

Regardless of birth appraisal, women discussed the value of support from their partners. Women who appraised their birth as non-traumatic described partners providing intuitive support and being present in the background, as well as discussing birth as a family event. For women who experienced a traumatic birth, discussions often consisted of feeling concerned for their partner during a chaotic birth environment or describing their partner as someone who had to defend and fight for them when the mother felt defeated.

Control: ‘That was really empowering, to know that, yes – it was me in control’

The second theme, control, consists of participants' perception of control over the birth environment, decisions made during labour, delivery or immediately postpartum and their confidence in their own bodies to deliver their baby safely. Women who appraised birth as non-traumatic expressed confidence that they could vocalise their needs and wishes and that they would be heard. In cases where participants' birth experiences deviated from their initial wishes, participants' priorities shifted to aspects of the birth they could still achieve (eg skin-to-skin contact or initiating breastfeeding), thus helping retain control and still have their needs met. Participants discussed how feeling included in decisions made around their birth contributed to feeling empowered, which coincided with women's perception of advice from healthcare professionals as guidance rather than instruction.

‘The hospital is there really, to help me, not the other way around, that's how I felt going in.’

Participant 8

Women who appraised their birth as non-traumatic also discussed a sense of internal control during birth, where they felt connected with their bodies and behaved instinctively to accommodate what their body needed. Women discussed maintaining a relaxed frame of mind during labour, having practiced relaxation techniques antenatally to facilitate this.

Informed: ‘I felt like I had options all the way through’

The third theme, informed, comprises women's perception of feeling informed and prepared from information received antenatally and during birth. Women who appraised birth as non-traumatic emphasised the power of being aware of options available to them before the birth. Consideration of alternative birth routes engendered a sense of preparedness and empowered women with choices over certain aspects of their birth. Participants also discussed the value of good communication with maternity staff, so that they felt aware of what was happening throughout more challenging moments of labour and delivery and given options of interventions or pain relief.

‘I was more aware of what my options were and what I was or wasn't allowed to ask for.’

Participant 12

Participants who discussed feeling informed often held an optimistic perception of their birth experience with an ‘end justified the means’ philosophy. Many women who appraised birth as non-traumatic outlined possible alternatives that would have been less desirable and discussed their actual birth experience as necessary for their situation.

Powerless

The themes within the category ‘powerless’ reflect participants' perception of feeling powerless during labour, birth, or immediately postpartum, and emerged predominantly from interviews with women who appraised birth as traumatic. A subtheme regarding limited antenatal and postnatal information was identified in interviews with all women, regardless of birth appraisal.

Distrust: ‘Nobody even knows my name’

The theme distrust consists of discussions surrounding participants' distrust towards healthcare services. Women who appraised birth as traumatic described the care they received as inconsistent and not catered towards them as an individual. Some women discussed impersonalised care in the context of a lack of staff or inconsistency in staff, preventing the development of trust and familiarity before, during and after birth. Women described feeling anonymous and as though healthcare providers had predetermined the plan for their birth as attention focused on the baby rather than the family unit as a whole, which contributed to women's sense of feeling disregarded.

‘You feel like you're a number and people don't actually see you, but they need to sign lots of papers and do loads of things, so they weren't looking at you as if you were a person.’

Participant 5

Women who appraised birth as traumatic expressed disappointment in the way their birth was managed within the healthcare service. Participants discussed feeling let down by their trust and feeling robbed of a special and positive childbirth experience.

Lack of control: ‘I didn't know what had happened to my own body’

The fifth theme, lack of control, comprises women's perception of lacking control over their birth, their environment or the decisions made during labour, delivery or immediately postpartum. One of the pertinent aspects of lacking control in participants' discussions of their traumatic birth experience was not having the power to choose the way their baby was born.

‘I wasn't in control - I was just having things done to me.’

Participant 7

Not having control over people entering the room or being unable to move into a desired position during labour, were aspects of the birth environment that caused some women to feel powerless.

Women who appraised birth as traumatic expressed a disconnect and lack of ownership over their birth. This was sometimes in the context of feeling physically disconnected from their bodies or feeling detachment as a result of not knowing what was happening, or from staff talking about them as if they were not present. Participants conveyed they did not feel they were treated with dignity during or immediately after their birth, which contributed to participants feeling vulnerable, exposed and defeated. Finally, they described feeling fearful for themselves or their baby as a result of a lack of control over what was happening during and immediately after their birth. Some women also expressed anxieties leading up to the birth. These included anxieties about having, or the possibility of having, a caesarean section, fear for themselves or their baby because of a previous traumatic birth, complications with the baby during pregnancy or feeling unsafe in the hospital.

In the dark: ‘No one was talking to me’

The final theme, in the dark, relates to women feeling in the dark before, during and after birth. Women who appraised birth as traumatic reflected on being uncertain of what was happening to them during or immediately after birth because of poor communication with healthcare providers. Some women expressed feeling as if they were not given the opportunity to discuss procedures before they were performed and were left unsure as to why procedures were performed in the first place. Other women described poor communication in the context of being given inconsistent information by staff.

Regardless of birth appraisal, all women discussed the information and services provided before and after birth as limited and not inclusive of all options or birth routes. Many women described taking the initiative to educate themselves on the science of labour and delivery during pregnancy and reported that their antenatal classes were not reflective of their experience. Participants voiced their concerns over gaps in postnatal support for both practical guidance on breastfeeding or recovery, and emotional support for women's mental health. Women who did access postpartum support often stated that they had to independently seek out support services.

‘You don't get a lot of help before you have the baby, let alone afterwards.’

Participant 11

Discussion

This study aimed to document women's experiences of both traumatic and non-traumatic childbirth to identify factors contributing to women's appraisals of their birth. Thematic analysis of interviews with women in the postpartum period revealed two main categories relating to whether mothers felt empowered or powerless during labour, birth and postpartum. As a result of the contrast between themes reflecting oppositional differences between birth experiences appraised as traumatic and non-traumatic, this discussion addresses each dyad of contrasting themes comparatively.

Empowered versus powerless

The empowerment of pregnant women is defined as a sense of self-fulfilment and increased independence, gained through interaction with their environment and other individuals, to achieve the pregnancy and childbirth they desire (Kameda and Shimada, 2008). Perinatal empowerment is associated with a more positive appraisal of birth and reduced postnatal depression symptoms (Nilsson et al, 2013; Garcia and Yim, 2017). Conversely, feeling powerless during birth has been associated with a negative birth experience (van der Pijl et al, 2020) and the development of psychological trauma and postnatal post-traumatic stress disorder (Soet et al, 2003). In the present study, perinatal empowerment was determined by the extent women felt trust, control and informed, despite diversity in birth experiences.

Trust versus distrust

A salient aspect of women's empowerment related to their interactions with the people around them during birth. Women who perceived their maternity care as personalised fostered a higher level of trust in maternity staff and were among those who appraised their birth as non-traumatic. The importance of trusting relationships with healthcare professionals has been attributed as a key component for a positive birth experience (Leap et al, 2010) and is particularly important for women with social risk factors (Rayment-Jones et al, 2019). The midwife–woman relationship is suggested to be the principal vehicle through which trust and empowerment are achieved (Perriman et al, 2018). Following a continuity model of midwife-led care is associated with improved neonatal outcomes, fewer clinical interventions and greater maternal satisfaction (Fair and Morrison, 2012; Sandall et al, 2016). Contrastingly, poor perceived support from healthcare professionals is associated with birth trauma (Elmir et al, 2010; Simpson and Catling, 2016) and many parents believe their trauma could have been reduced or prevented by better communication and support from their caregiver (Hollander et al, 2017). In the present study, women who appraised birth as traumatic described de-individuated care, feelings of anonymity and distrust in a system that felt impersonal and ‘manufactured’. Trust in partners was a common subtheme apparent in all women's birth stories, which highlights the value of birth companions to provide a sense of familiarity and feeling valued and respected (Kirova and Snell, 2019). This was particularly reassuring for women who experienced inconsistent maternity care. Having a partner or continuously present birth professional is known to improve psychological and obstetric outcomes for both mothers and their newborns (Bohren et al, 2019).

Control versus lack of control

Perception of control was crucial to women's empowerment during birth. Women who appraised birth as non-traumatic discussed possessing an element of control over the decisions that were made. Self-determination is a key component of what is considered a ‘good’ birth and is defined as the ability to have a birth shaped and guided by one's own inclinations and values rather than those of others (Namey and Lyerly, 2010). Having control in this context requires attentive staff support to give women the confidence that their voices are heard and ensure women play an active role in decisions (O'Hare and Fallon, 2011). While women do not always desire complete autonomy during birth, a sense of choice and control is associated with greater satisfaction and decreased maternal anxiety (Cheung et al, 2007; Christiaens and Bracke, 2007; Fair and Morrison, 2012). A willingness to relinquish control to healthcare professionals can paradoxically enhance one's sense of control during birth, but it is the agreeableness to relinquish control that is important, which relies upon a foundation of trust (Green, 1999; O'Hare and Fallon, 2011). Indeed, issues can arise if the mother experiences uncertainty or perceives herself to be an unequal participant in a medical world (Snowden et al, 2011). In the present study, women who appraised birth as traumatic reflected on not having a choice over the way their baby was born or the way their maternity care was managed. Women's sense of agency can be compromised by unresponsive caregiver interactions and in turn, evoke feelings of inadequacy, vulnerability and the sense of ‘falling apart’ during birth (Elmir et al, 2010). This highlights the delicate interplay between women's perception of feeling supported and feeling in control in childbirth.

Informed versus in the dark

The final themes related to how informed mothers felt before, during and after birth. Women who appraised birth as non-traumatic discussed feeling prepared and aware of their options because of information received before and during birth. Being aware of the options, and consequently empowered with choices, likely facilitated women expressing an ‘ends justifies the means’ mentality when reflecting on aspects of their birth that deviated from their desired labour and delivery (Cook and Loomis, 2012). Yet, a prerequisite to being aware of options is good communication with maternity staff. Women who appraised birth as traumatic reflected on poor communication with staff, feeling left out of discussions and uninformed of the risks and benefits of procedures. There is evidence that poor communication with maternity staff can lead to an increase in mental health problems postnatally (Baker et al, 2005) and reluctance to engage with postnatal support services (Raine et al, 2010). Receiving inconsistent information regarding birth options can also affect a woman's sense of security over their birth (Munch et al, 2020).

An element of feeling in the dark expressed by all women in this study was inadequate information and support provided antenatally and postnatally. This finding is consistent with previous perinatal research in the UK. Lavender et al (2000) reported that in the UK, mothers described antenatal information as unrealistic and not tailored to their individual needs and Cumberlege et al (2016) reported that women expressed a lack of critical physical and mental health support from healthcare providers in the immediate postnatal period. In the present study, the availability of information and support before and after birth did not necessarily contribute to a traumatic appraisal of birth, yet its relevance in terms of empowering women during the perinatal period was significant for all mothers.

Conclusions

The current study explored women's subjective birth experiences that contribute to women's appraisal of traumatic or non-traumatic childbirth. The comparative nature of thematic analysis provides a novel framework of factors relating to how empowered or powerless a mother feels. A woman's level of empowerment is determined by the trust she has in those supporting her and her level of control and understanding of birth events. Ultimately, many of the themes relate to the relationship between a mother and the people around her. This study provides further evidence that the consistency and quality of care provided during birth is a core factor in how women reflect on their childbirth experience. Many of the interpersonal factors identified are addressed in the national ‘Better Births’ report, which outlines the need for consistent and personalised maternity care, better communication of information and access to postnatal support (Cumberlege et al, 2016).

Key Points

- Feeling empowered or powerless was a distinguishing factor between women who found birth non-traumatic or traumatic.

- Perinatal empowerment arises from a sense of trust, control and feeling informed during labour, birth and immediately postpartum.

- The relationship between the mother and the people around her during birth is at the heart of perinatal empowerment.

- Asking women about their sense of empowerment may be a useful predictor of birth trauma.

CPD reflective questions

- What practices can healthcare staff implement to ensure women's sense of empowerment, trust and control throughout their birth?

- How can healthcare staff facilitate an emotionally and physically safe environment if and when women are unable to receive consistent care throughout their births?

- How can healthcare staff ensure that women receive all the relevant perinatal information, and are consistently informed throughout their birth?

- What practices can be implemented to decrease miscommunication between parents and healthcare staff?