A Cochrane review of debr iefing interventions for the prevention of psychological trauma in women following childbirth was published in 2015 (Bastos et al, 2015). Seven trials were included in the review, which took place in three countries. Debriefing was not narrowly defined, or dependent on being labelled ‘debriefing’, which allowed the inclusion of the maximum number of studies.

Bastos et al (2015) identified two main types of debriefing: postnatal debriefing and psychological debriefing. Postnatal debriefing was commonly a meeting with a midwife, at which women discuss their birth events with reference to the medical notes. Psychological debriefing was found to be more structured and usually involved a set of procedures aimed at preventing psychological morbidity. This Cochrane review, set in the maternity context, did not find clear evidence that debriefing either reduced or increased the risk of developing psychological trauma during the postpartum period, a finding that was due to the poor quality of the evidence and heterogeneity between the studies.

The authors concluded that routine psychological debriefing for women after childbirth could not be supported; however, they highlighted that other forms of postnatal discussion with women after birth, such as the unstructured form recommended by the National Institute of Health and Care Excellence (NICE) (2007; 2014), should continue (Bastos et al, 2015). As a consequence, the most recent practice guidance recommends that healthcare providers should not ‘offer single-session, high-intensity psychological interventions with an explicit focus on “re-living” the trauma to women who have a traumatic birth’ (NICE, 2014: 38). However, there was heterogeneity between the studies, with different approaches to ‘debriefing’ that were often poorly described. There is a clear need for more high-quality randomised controlled trials using similar groups of women, interventions and outcome measures, in order to address the lack of robust findings.

Literature review

Anecdotal evidence suggests that women value postnatal listening services and that some maternity services continue to provide them. The rationale for this study stems from a critical review of the literature on women's and professionals' perceptions and experiences of postnatal debriefing (Baxter et al, 2014). The main aims were to describe current practice in offering debriefing services to postpartum women, and to learn about the perceptions of midwives and women accessing these services. This differed to the type of research covered by the Cochrane review which only included RCTs. The literature review identified two different types of postnatal debriefing sessions: structured and unstructured (Baxter et al 2014). The unstructured type of session was usually found to be provided by midwives, with names such as ‘Birth Reflections’ or ‘Birth Afterthoughts’.

Niven (1992: 34) defines how debriefing using a less structured approach may help women postnatally:

‘Just listening to fears, worries and problems and not seeking to obliterate or solve them but to facilitate their ventilation is a crucial part of psychological care.’

This quotation suggests subtle but potentially important differences in meaning and interpretation between the original concept of structured psychological debriefing and how debriefing is typically used in maternity care. This could underlie the differing findings from the trials included in the Cochrane review.

The findings of the literature review indicated key benefits. Postnatal debriefing was found to satisfy women's need to talk, be listened to, receive information and gain a greater understanding of their experience (Baxter et al, 2014). This was facilitated by telling the story of their birth experiences to a midwife (Inglis, 2002; Gamble et al, 2004; Bailey and Price, 2008).

Debriefing was also identified as being therapeutic. Women who had experienced a traumatic birth felt they had benefitted. Some women who had a traumatic birth experienced flashbacks, but talking about their experiences helped relieve some of their symptoms. It was not only women with trauma symptoms who felt they had benefited: other women also needed to have their voice heard and air their feelings about their birth experience (Inglis, 2002).

The process by which debriefing had helped these women was not always explored nor made explicit; however, the opportunity to talk, identify concerns and have questions answered may have provided the necessary information to enable a woman to gain an acceptance of what happened to her when she gave birth.

The literature review (Baxter et al, 2014) also found that postnatal debriefing also provided an opportunity for midwives to give women a detailed breakdown and explanation of the events that occurred during their labour and birth using the maternity case notes (Dennett, 2003; Gamble et al, 2004). Midwives were able to sit with women and read through the records made by midwives and obstetricians during her labour, which provided the woman with further clarity about how events occurred and progressed.

The literature review (Baxter et al, 2014) also identified a lack of clarity about the nature of debriefing services and how women experienced them. However, the limited number of studies found that women (5 studies) and midwives (2 studies) perceived that it was good for women to talk and be listened to after giving birth.

Methods

Design

This study is focused on a service that provided an unstructured form of debriefing, which was commonly provided by a midwife. In 2013 when this research study was being planned, all women who gave birth at the study hospital typically received an invitation to return to the study hospital to discuss their birth experience with a midwife. This provided an opportunity for the study to gain more information about women's views and experiences, given the generally positive responses from women identified in the literature review (Baxter et al, 2014). This would help to understand more fully women's psychological support needs immediately following birth and plan services accordingly.

Owing to the limited research on women's experiences of postnatal debriefing, an exploratory study was appropriate. A quantitative postal survey was conducted to assess women's experience of attending a birth reflections-type service and their feelings after giving birth.

Participants

The sample consisted of women who gave birth during one calendar month at at an integrated acute and community NHS Trust in the home counties. This process modelled that used by the researchers of the national maternity survey in England (Care Quality Commission (CQC), 2018). It was expected that using this approach, data would be obtained from more than 200 women, since approximately 500 women gave birth at the study hospital each month at the time of data collection.

Measures

Information obtained in the literature review (Baxter et al, 2014) was used to guide the development of the questionnaire. Adding to validity, some questions were taken from instruments previously used in other studies (McCourt and Page, 1996; Beake et al, 2001; Fitzgerald et al, 2002).

In the survey, women were asked about their feelings after giving birth and whether they understood what had happened to them. They were also asked whether they felt the need to have a discussion with a health professional after they went home and whether they were aware of the Birth Reflections service. The women were also asked to complete the impact of events scale (IES). The IES is used to assess subjective distress for a life event and the testing is described in Horowitz et al (1979). The event under question was women's recent birth experience. This instrument includes 15 statements regarding the psychological constructs of avoidance (such as ‘I tried to remove it from my memory’) and intrusion (such as ‘I thought about it when I didn't mean to’) (Horowitz et al, 1979). Avoidance and intrusion are recognised symptoms of post-traumatic stress (PTS).

It was important to understand how women felt about their birth experience, as this could provide further explanation about their desire (or not) to attend the Birth Reflections service. This scale was used as a proxy indicator for PTS and both terms, PTS and IES, were used interchangeably in this study.

The responses to each of the questions were combined to produce an overall score. Horowitz (1982) specified bands of symptoms: in which a score of 0–8 was ‘low’; 9–19 was ‘moderate’ and 20+ was ‘severe’. For simplicity, analyses combined the moderate and severe categories to give a dichotomous classification of ‘low’ (0-8) and ‘high’ (≥9).

Although this tool has not been formally validated for use in the maternity context, this has been used by other authors in the field of childbirth (Ryding et al 1998; Selkirk et al, 2006).

Procedure

The questionnaire was piloted during a focus group. Six women attended this event, each of whom completed a questionnaire. The instrument was amended in line with their feedback.

The finalised survey was sent to all women who gave birth at the study hospital during June 2013. A total of 447 surveys were posted to these women during October and November 2013. Responses were received from 170 women (38%).

Analysis

The data from the questionnaires were managed and analysed using SPSS version 22. Descriptive statistics were used as well as cross tabulations to determine possible differences in the responses of different groups. Chi-square (c2) and Mann Witney U tests were conducted where appropriate.

Survey findings

The findings are presented in three main sections: demographic characteristics, women's perceptions of the Birth Reflections service and women's experiences of labour and birth.

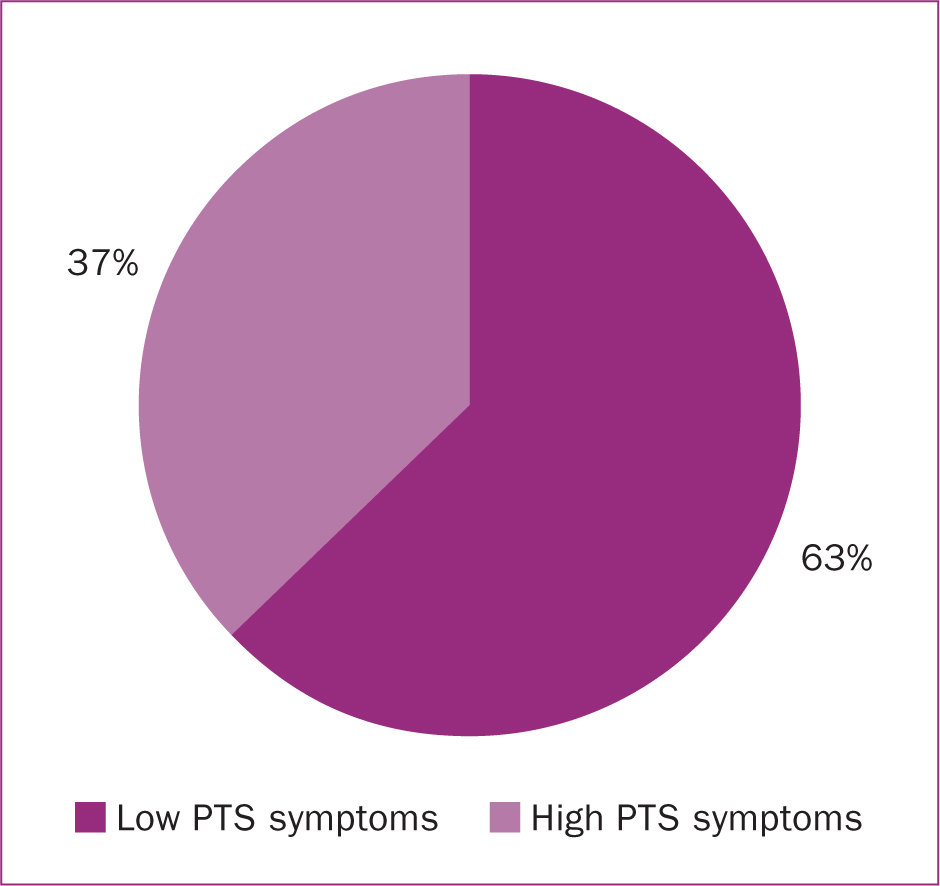

Of the women in this sample, 37% were found to have high PTS symptoms (Figure 1).

Demographics

Table 1 shows the sample was comprised of predominantly white, highly educated women, reflecting the majority local population. On other demographic and obstetric characteristics, the sample was representative of the UK population of childbearing women. More women in this sample were first-time mothers (51%) compared to national findings in England for 2013–2014 (37%) (Health and Social Care Information Centre, 2015). More women in this sample had an operative or instrumental birth (44%) compared to the rate for the UK (39%) (Health and Social Care Information Centre, 2015).

| Variable | n (%) | |

|---|---|---|

| Ethnicity | White British | 136 (80) |

| White other | 13 (7.6) | |

| White and black African | 1 (0.6) | |

| White and black Caribbean | 3 (1.8) | |

| White and Asian | 2 (1.2) | |

| Indian | 2 (1.2) | |

| Pakistani | 8 (4.7) | |

| Other Asian background | 3 (1.8) | |

| Other ethnic group | 1 (0.6) | |

| Age (years) | 20–24 | 14 (8.2) |

| 25–29 | 29 (17.1) | |

| 30–34 | 71 (41.8) | |

| 35–39 | 45 (26.5) | |

| ≥40 | 11 (6.5) | |

| Level of education | GCSE | 18 (11.5) |

| A level or diploma | 28 (17.9) | |

| Degree | 80 (51.3) | |

| Postgraduate degree | 17 (10.9) | |

| Professional including NVQ | 13 (8.3) | |

| Parity | Primiparous | 86 (50.6) |

| Multiparous | 84 (49.4) | |

| Type of birth | Normal vaginal | 95 (55.9) |

| Ventouse | 8 (4.7) | |

| Forceps | 28 (16.5) | |

| Elective caesarean section | 13 (7.6) | |

| Emergency caesarean section | 26 (15.3) | |

NVQ: national vocational qualification

Perceptions of the Birth Reflections service

Table 2 shows findings about women's desire to speak after birth. The results show a significant difference between those with high and low levels of PTS symptoms. Those with high levels of PTS symptoms were more likely to think about labour at home, to have a greater need to talk to a professional, and to talk more about labour and birth. They were also less likely to have understood what happened during labour and birth and were more dissatisfied with their understanding. However, the results also showed many women found opportunities to talk with other professionals after giving birth.

| Total† | Level of PTS symptoms n (%) | χ2 | df | P | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Low (≤8) | High (≥9) | |||||

| I think about labour at home | 155 | 97 | 58 | 28.3 | 2 | 0.000** |

| Yes, often | 75 (48) | 32 (33) | 43 (74) | |||

| Yes, sometimes | 61 (39) | 46 (47) | 15 (26) | |||

| No | 19 (12) | 19 (20) | 0 (0) | |||

| I needed to talk to a professional | 154 | 97 | 57 | 20.2 | 5 | 0.001** |

| Yes but I did not do so | 15 (10) | 4 (4) | 11 (19) | |||

| Yes and I spoke with a midwife about this but not as part of the Birth Reflections service | 33 (21) | 18 (19) | 15 (26) | |||

| Yes and I spoke with another health professional about this but not as part of the Birth Reflections service | 14 (9) | 6 (6) | 8 (14) | |||

| Yes I attended the Birth Reflections service | 1 (1) | 1 (1) | 0 (0) | |||

| No | 83 (54) | 64 (66) | 19 (33) | |||

| Don't know | 8 (5) | 4 (4) | 4 (7) | |||

| I wanted to talk more about labour and birth | 156 | 99 | 57 | 36.4 | 3 | 0.000** |

| Yes, someone who was there | 35 (22) | 11 (11) | 24 (42) | |||

| Yes, someone who was not there | 3 (2) | 1 (1) | 2 (3) | |||

| Yes, whether or not they were there | 16 (10) | 5 (5) | 11 (19) | |||

| No, not really | 102 (65) | 82 (83) | 20 (35) | |||

| I understood what happened during labour and birth | 156 | 99 | 57 | 20.6 | 2 | 0.000** |

| Yes | 115 (74) | 85 (86) | 30 (53) | |||

| No | 26 (16) | 9 (9) | 17 (30) | |||

| Don't know | 15 (10) | 5 (5) | 10 (18) | |||

| I was satisfied with my understanding of labour and giving birth | 157 | 99 | 58 | 8.3 | 2 | 0.016* |

| Yes | 122 (78) | 84 (85) | 38 (66) | |||

| No | 16 (10) | 6 (6) | 10 (17) | |||

| Don't know | 19 (12) | 9 (9) | 10 (17) | |||

PTS: post-traumatic stress.

Total for women with a PTS score.

Significant at 95%;

at 99%

Of the respondents, 30% said they knew about the service but chose not to attend, and another group of respondents said that they did not know about it but felt that they would not have attended anyway. However, 40% said they were unaware of the service and would have liked to have had the opportunity to attend. More women in this group were found to have higher IES scores (Table 3).

| Total† | Level of PTS symptoms n (%) | χ2 | df | P | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Low (≤8) | High (≥9) | |||||

| I remember receiving a Birth Reflections form | 156 | 98 | 58 | 0.88 | 2 | 0.643 |

| Yes | 69 (44) | 41 (42) | 28 (48) | |||

| No | 44 (28) | 30 (31) | 14 (24) | |||

| Don't know | 43 (28) | 27 (28) | 16 (28) | |||

| Reason for not attending Birth Reflections | 145 | 90 | 55 | 11.7 | 3 | 0.008** |

| I knew about the service but deliberately chose not to attend as I did not feel the need | 27 (19) | 23 (26) | 4 (7) | |||

| I knew about the service but didn't use for other reason | 18 (12) | 10 (11) | 8 (15) | |||

| I did not know about it but would not have attended anyway | 44 (30) | 30 (33) | 14 (25) | |||

| I did not know about it and would have like to have attended | 56 (39) | 27 (30) | 29 (53) | |||

PTS: post-traumatic stress.

Total for women with a PTS score.

Significant at 95%;

at 99%

Women's experiences of labour and birth

In order to understand women's need to talk and feelings about their birth experience, it was important to hear about their experiences during labour and birth. Table 4 summarises the main findings for the experiences of labour and birth of the women in the sample by whether they experienced low or high PTS symptoms. Various measures were used, each highlighting a different aspect of the birth experience. Overall the perception was positive: over 90% of women were satisfied with the care they were provided during labour and birth. However, Table 4 indicates that women with high PTS symptoms rated all aspects of the birth experience as worse. Women with high PTS symptoms were significantly less satisfied with care, more disappointed with their birth experience, and their expectations of birth and labour were less likely to be met.

| Total for women with PTS score | Level of PTS symptoms n (%) | P *Significant at 95%; **at 99% | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Low (≤8) | High (≥9) | |||

| Satisfaction with care | n=157 | n=99 | n=58 | 0.016* |

| Excellent | 68 (43) | 49 (50) | 19 (33) | |

| Very good | 60 (38) | 36 (36) | 24 (41) | |

| Good | 16 (10) | 10 (10) | 6 (10) | |

| Fair | 9 (6) | 3 (3) | 6 (10) | |

| Poor | 4 (3) | 1 (1) | 3 (5) | |

| Feelings about the birth experience | n=156 | n=98 | n=58 | 0.000** |

| Very disappointed | 10 (6) | 2 (2) | 8 (14) | |

| Disappointed | 21 (14) | 6 (6) | 15 (26) | |

| Neither/nor | 24 (15) | 13 (13) | 11 (19) | |

| Pleased | 56 (36) | 41 (42) | 15 (26) | |

| Very pleased | 45 (29) | 36 (37) | 9 (16) | |

| How well they feel they managed labour | n=157 | n=99 | n=58 | 0.074 |

| Very well | 64 (41) | 44 (44) | 20 (35) | |

| Quite well | 53 (34) | 33 (33) | 20 (35) | |

| Alright | 31 (20) | 22 (22) | 9 (16) | |

| Not very well | 6 (4) | 0 (0) | 6 (10) | |

| Not at all well | 3 (2) | 0 (0) | 3 (5) | |

| Expectations of labour met | n=146 | n=90 | n=56 | 0.017* |

| Much better | 26 (18) | 17 (19) | 9 (16) | |

| Better | 30 (21) | 22 (24) | 8 (14) | |

| About the same | 46 (32) | 32 (36) | 14 (25) | |

| Worse | 31 (21) | 14 (16) | 17 (30) | |

| Much worse | 13 (9) | 5 (6) | 8 (14) | |

| Expectations of birth met | n=154 | n=97 | n=57 | 0.000** |

| Much better | 41 (27) | 31 (32) | 10 (18) | |

| Better | 33 (21) | 25 (26) | 8 (14) | |

| About the same | 38 (25) | 26 (27) | 12 (21) | |

| Worse | 24 (16) | 10 (10) | 14 (25) | |

| Much worse | 18 (12) | 5 (5) | 13 (23) | |

| Overall labour and birth (χ2=9.27 (excludes ‘other’); df=2) | 0.01** | |||

| Awful | 18 (12) | 6 (6) | 12 (21) | |

| OK in the end | 52 (34) | 29 (30) | 23 (40) | |

| Hard work but wonderful | 72 (47) | 51 (53) | 21 (37) | |

| Other | 11 (7) | 10 (10) | 1 (0.7) | |

Discussion

This study has found that nearly half (41%) of a small sample of women who gave birth at a maternity unit in England in 2013 wished to discuss their birth experience with a midwife. This finding was exploratory but may be replicated in other samples and concurs with findings from a critical review of the literature (Baxter et al, 2014). In a qualitative study, Ayers (2007) found that all women, including those with PTS symptoms, went through a ‘postnatal appraisal process’, in which they processed their memories of birth (Ayers, 2007:262). However, 40% of the women who responded to the survey said they did not know about the Birth Reflections service and that, had they done so, they would have chosen to attend.

The findings indicate that women who had positive feelings about their labour and birth experience were less likely to need to speak about it afterwards. In addition, women who reported experiencing effective support during labour were more likely to have a clear understanding of what happened to them.

This study provides an understanding about how women are left feeling after giving birth. It is of concern that approximately one-third of the respondents had an IES score above 8, suggesting that they were experiencing some symptoms of PTSD. This concurs with the work of others, such as Harris and Ayers (2012), who highlighted that 20–48% of women rated childbirth as traumatic, with many reporting some symptoms of PTSD. Furthermore, an overview of research in this area reported prevalence rates of actual PTSD of up to 6.9% (Ayers et al, 2008).

Through the use of the IES, this study identified an association between women's experiences of labour and birth and their IES score. Women with a high IES score or high PTS symptoms were more likely to have a negative birth experience, to wish to talk with a health professional or to attend the Birth Reflections service. These findings highlighted an association between a negative birth experience and emotional distress. Women who have increased levels of distress are more likely to need additional support from professionals.

To the author's knowledge, the IES has been used in two studies in the maternity context. In these studies the IES was used as an outcome variable, to prove whether a form of postnatal debriefing is effective, shown by a reduced IES score, for example (Ryding et al 1998; Selkirk et al, 2006). In Australia, Selkirk et al (2006) used the IES along with several other measures to assess the effect of midwife-led postpartum debriefing on psychological variables. Generally, the results did not support midwife-led debriefing as an effective intervention postnatally; however, the sample was small, with 149 women in both arms of the RCT. In Sweden, Ryding et al (1998) used the IES in a similar way to test a model of postpartum counselling for women after emergency caesarean section. Women's cognitive appraisal of the delivery was more positive than the comparison group at 1 and 6 months postpartum.

The IES has been used in an entirely different way in this study, where it has been used to describe how women were feeling after giving birth, rather than as an outcome measure in an RCT. This study found statistically significant differences by using the IES to compare different groups of women.

It is possible that these results may be generalised to other maternity populations but there is a need for caution for several reasons. The response rate to the survey, anticipated in the planning stages of the study to be around 50%, was lower than expected (38%). Although this is comparable with other maternity surveys (CQC, 2018), it is possible that the responses were skewed to women with particular views or from particular backgrounds (for example, more women than average in this sample had experienced an instrumental birth). Additionally, the survey respondents were on average highly educated and of white, European ethnicity. This reflects the demographics of the context of the study, but a wider study would be needed to be able to generalise to other populations.

Implications for practice

It appears there are various different groups of women who may benefit from attending a birth reflections session and have a postnatal debriefing following birth.

Tables 2 and 3 indicate that there was a strong desire from subgroup of women to talk further about their birth experience. However, as different groups of women were considered to need formal psychological debriefing or a more informal meeting with a health professional to discuss their birth experience, this may indicate the need for all women to be offered the service. Some may not feel the need (Table 3) but others, particularly those exhibiting high PTS symptoms, might. Although it is possible to clearly identify some women who may be at particular risk of psychological trauma (eg after an emergency during the birth), there will also be other women affected by the birth experience who go home from the hospital and struggle to come to terms with what happened to them. There is the possible need to standardise postnatal debriefing as part of routine postnatal care provision.

Free text comments from women in the survey indicated that their lives as new mothers were busy and finding time to attend a Birth Reflections meeting proved difficult. This study identified the need to record women's feelings after their experiences of giving birth and it may be more practical to undertake this as part of routine postnatal care; however, this service is already overloaded. The findings of successive surveys undertaken by the health care regulator indicate that postnatal care is often of poor quality and not always perceived well by women (Care Quality Commission, 2018).

In addition there have been recent steps taken to reduce home visits by midwives in England. Managers of these services should be wary of reducing postnatal home visits as they can not only identify physical clinical problems but can also recognise if a woman is struggling emotionally. Women's feelings are unlikely to be picked up on in busy postnatal wards and this may well be too early to do so. Traditionally, community midwives who knew the women would observe them on home visits; however, this kind of care is being withdrawn in favour of asking women to seek care if they need it.

There is a need to improve postnatal care provision while also introducing universal postnatal debriefing sessions for women on an opt-out basis. This will ensure that women's feelings after giving birth are addressed appropriately, leading to increased satisfaction of postnatal care, while ensuring that those who do not wish to have such a discussion are not required to do so.

Conclusion

The period after birth is an under-researched area, and few studies have explored how women feel at this time. In the UK, surveys have consistently shown women are more disappointed and dissatisfied with their postnatal care, compared to other aspects of maternity care (Redshaw and Henderson, 2015; Care Quality Commission, 2018). This study has added to the literature in this area. It has shown a link between how an individual woman feels postnatally and her birth experience. Analysis using the IES as an explanatory variable with a general sample of postpartum women identified that women's appraisals of their experiences of labour and birth differed according to their IES score. Women with high levels of PTS symptoms were more likely to have a negative birth experience, wish to talk with a health professional or to attend the Birth Reflections service. Women with low PTS symptoms were more likely to rate the birth experience positively and less likely to want to attend the Birth Reflections service. This, to the author's knowledge, has not been found elsewhere. These findings provide further evidence for the concept of a negative birth experience and highlight an association between a negative birth experience and emotional distress. Women who have increased levels of distress are more likely to need additional support from professionals.

This research is highly pertinent and relevant. A national review of maternity care in England lists ‘better perinatal and postnatal care’ as one of its seven key themes for areas of improvement (National Maternity Review, 2016). The findings from this study provide useful information to guide this improvement as part of plans for investment in both perinatal mental health and routine postnatal care. The findings relate to both these important aspects of care provision. Although the majority of women report a positive experience of giving birth, one-third of women who responded to this survey were found to have raised PTS symptoms. These women experienced negative emotions linked to the birth that should be addressed, for example by discussing their experience of giving birth postnatally with a midwife who is able to respond to unanswered questions. Women with more extreme psychological symptoms will benefit by the offer of referral to another health professional.