Preterm birth, or birth before 37 weeks gestation, is known to cause short and long term problems. Preterm babies are more at risk of developmental problems and disorders; a risk known to lessen with advancing gestational age (Kallioinen et al, 2017). In England and Wales, around 7.5% of babies are born preterm, with 0.4% born before 28 weeks (Kallioinen et al, 2017). Further details regarding the Department of Health and Social Care's (DHSC) vision for reducing the national preterm birth rate and improving maternity care can be found in the Safer Maternity Care policy (DHSC, 2017)

In 2016, Rosie Hospital, Cambridge had 5688 births, with 381 women (6.7%) having spontaneous preterm deliveries. Although this is below the national level, it still presents a significant demand for future screening of high-risk women in their subsequent pregnancies. Previously, high-risk women were seen in the antenatal clinic and referred to the scan department for cervical length screening. An audit was carried out, which demonstrated variation in both the referral and management of these women. As a result of the audit, guidelines from the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) (2015), and patient feedback, the preterm surveillance clinic was established. Dedicated preterm surveillance clinics are not widely available in all UK obstetric units: Sharp and Alfirevic (2013) found that only 23 of 144 (15.0%) of NHS hospitals had specialist clinics, despite evidence suggesting that they are an effective way of managing high-risk women and avoid unnecessary admissions (Min et al, 2016). Dedicated preterm clinics may also provide emotional and psychological benefits for women through improved continuity of care (Malouf and Redshaw, 2017).

The preterm surveillance clinic is run by a multidisciplinary team made up of midwives, sonographers and a consultant obstetrician. The clinic runs on Thursday mornings in the maternal medicine unit at Rosie Hospital, Cambridge.

Given the lack of national guidance on the specifics of preterm surveillance, the aim of this article is to discuss the practicalities of establishing a dedicated preterm surveillance clinic, including how to identify high-risk women, what surveillance can be offered, how to standardise the transvaginal ultrasound cervical assessment, and suggested management pathways.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

All pregnant women are offered two antenatal scans regardless of their preterm birth risk or medical history. The first scan is between 11-14 weeks for combined screening and the second between 18-21 weeks to assess the fetal anatomy. High-risk woman are offered additional scans, which may include transvaginal cervical assessment. Transvaginal cervical assessment is used in the second trimester to identify women with a short cervix, which can lead to preterm birth. There are numerous risk factors associated with preterm birth, which are summarised in Table 1.

| Type of risk factor | Risk factor |

|---|---|

| Infection | Urinary tract infection (UTI) |

| Sexually transmitted infection (STI) | |

| Vaginal infections such as bacterial vaginosis (BV) and trichomoniasis | |

| Obstetric factors | Vaginal bleeding and placenta previa |

| Some fetal abnormalities or gestational diabetes which can cause polyhydramnios | |

| Previous uterine surgery, such as caesarean, increasing the risk of uterine rupture | |

| Previous cervical surgery such as large loop excision of the transformation zone (LLETZ), cone biopsy or trachelectomy | |

| Multiple pregnancy | |

| Previous spontaneous preterm birth or mid-trimester loss | |

| Maternal factors | Maternal age; under 18 or over 35 |

| Congenital uterine anomaly such as bicornuate or didelphic uterus | |

| High blood pressure | |

| Low body mass index (BMI) | |

| Afro-Caribbean ethnicity | |

| Social factors | Smoking |

| Low socio-economic status | |

| Alcohol or drug misuse | |

| Domestic violence including physical, sexual or emotional abuse | |

| Stress |

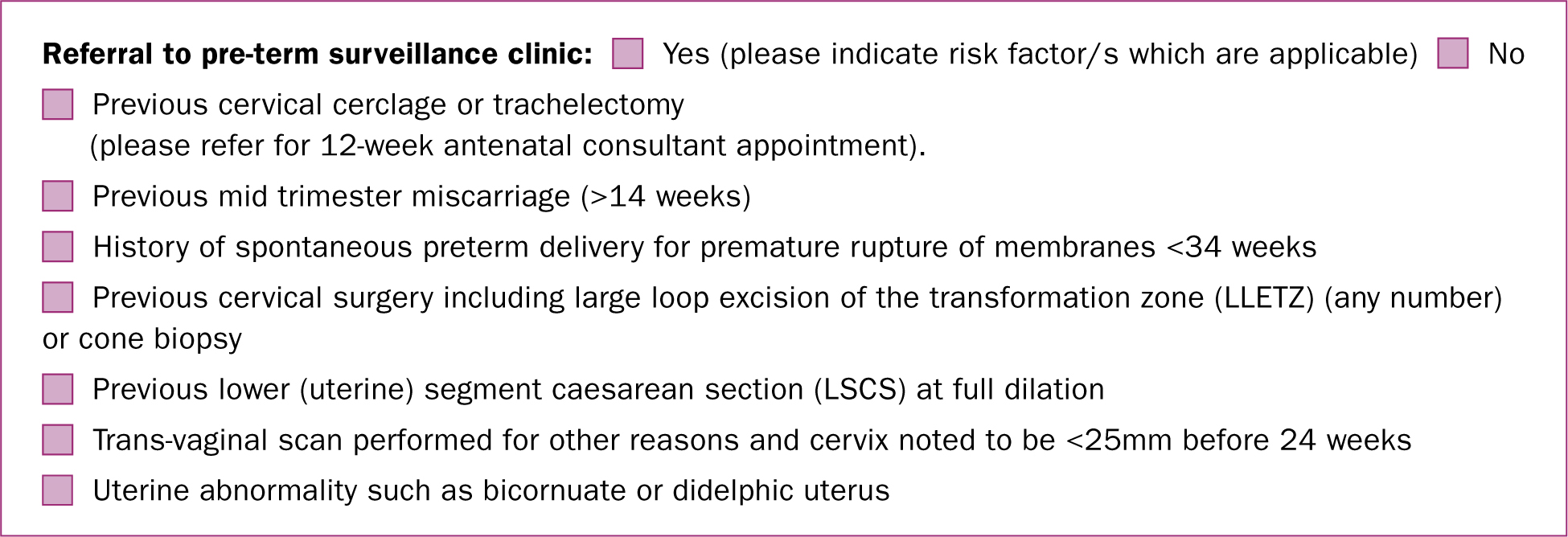

There is no detailed national guidance on inclusion criteria for preterm surveillance other than the recommendation that women who have experienced a previous preterm birth or mid-trimester loss should have surveillance (NICE, 2015). According to the Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine (SMFM), there is insufficient evidence to justify universal transvaginal cervical length screening for all pregnant women (SMFM, 2016). The inclusion criteria for cervical surveillance at this preterm surveillance clinic therefore reflect the risk factors for cervical shortening, which were developed after discussion with other Trusts with established preterm surveillance clinics, and evaluation of the supporting literature (Crane et al, 2015; NICE, 2015). Women are offered surveillance if they have:

Caesarean sections performed at full dilation can result in an incision in the cervix rather than lower uterine segment (Zimmer et al, 2004) and have been shown to have an association with subsequent preterm birth in future pregnancies (Carter et al, 2014; Levine et al, 2015; Wood et al, 2017). Women who have had any number of LLETZ procedures are included as a woman can still have a significant amount of cervical tissue removed, even after one treatment (Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists, 2016). The clinic team have subsequently collaborated with the colposcopy department to ensure patients are given a letter after their LLETZ treatment, advising them to seek preterm surveillance in their future pregnancies.

Exclusion criteria are conditions not associated with cervical shortening. These include:

The referral process

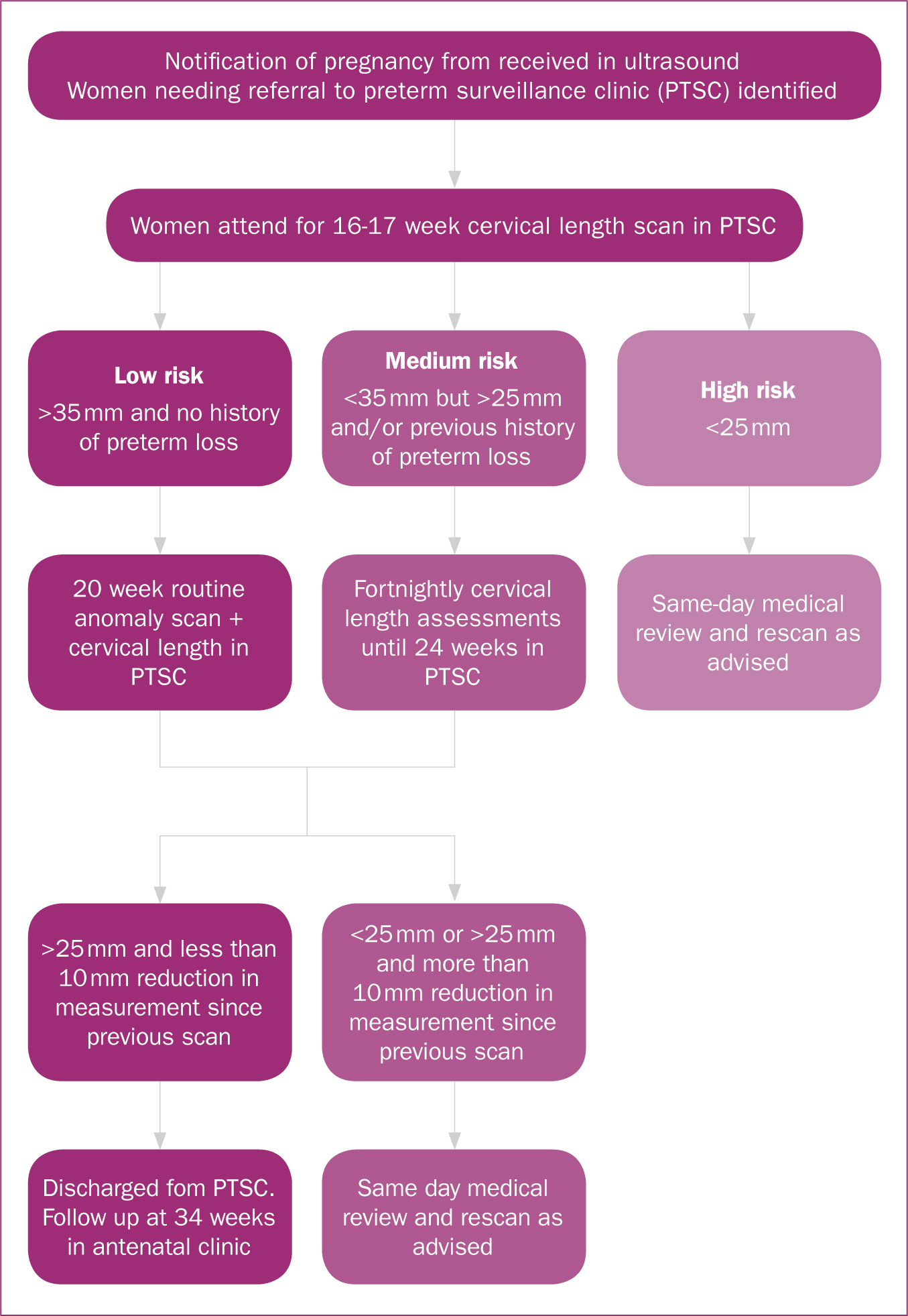

Before the introduction of the preterm surveillance clinic, there was concern that not all women at risk of preterm labour were referred for cervical surveillance. Consequently, the notification of pregnancy form has been modified, so that when the form is completed at booking by a midwife, they ask specifically ask about risk factors (Figure 1). In accordance with NICE (2015) guidance, all women identified as having risk factors are given information about the signs and symptoms of preterm labour and contact numbers for the clinic.

Signs and symptoms of preterm labour may include (Katz et al, 1990):

What surveillance is offered?

Women with singleton pregnancies who meet the inclusion criteria for cervical surveillance are referred for a scan at 16–17 weeks. Before this, gestation measurements of the cervical length are less reproducible, as the internal os is difficult to identify and the uterine isthmus may be inadvertently included in the ultrasound measurement (Greco et al, 2012).

Women attending the clinic are asked to provide a mid-stream urine specimen and have a low vaginal swab taken to exclude to exclude genitourinary infections, such as bacterial vaginosis, which are known to be associated with preterm birth (Goldenberg et al, 2005). Women then have a trans-abdominal ultrasound scan to assess fetal viability and amniotic fluid before a transvaginal ultrasound scan for cervical assessment.

Combined transvaginal ultrasound cervical length and fibronectin testing can be an effective way of screening women at risk of preterm labour (Kuhrt et al, 2016). Fetal fibronectin is a ‘glue-like’ protein present between the amnion and chorion, detectable in vaginal secretions at the very beginning of pregnancy and again after the 35th week of pregnancy. Detection of fetal fibronectin before 35 weeks can predict preterm birth. The European Association of Perinatal Medicine recommends combining biochemical markers and cervical length measurements to identify women at immediate risk of preterm birth (Di Renzo et al, 2017). Fibronectin testing is not supported by NICE and due to cost implications, the clinic is unable to offer it to women attending for preterm surveillance. However, the combination of ultrasound, medical history and fibronectin would be advantageous in identifying women most at risk of preterm birth and could possibly reduce the frequency of clinic visits and the need for admission for some women.

Standardising the transvaginal cervical length assessment

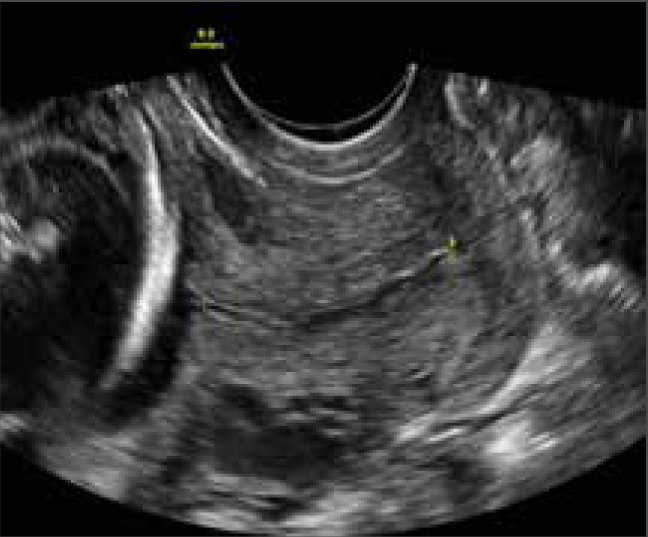

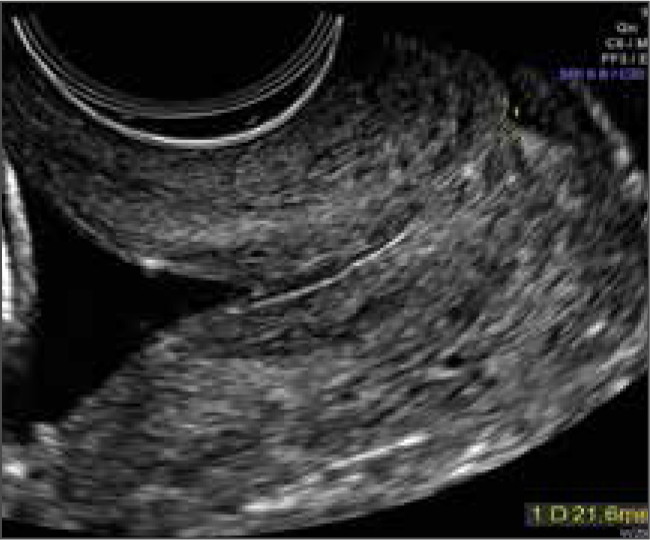

Accurate cervical length measurements are important, as even small differences can have a significant effect on patient management and their perceived risk of preterm birth, particularly near the 25 mm threshold. Intra-operator variability of between 3.9-7.3 mm and inter-operator variability of up to 10 mm have been reported (Valentin and Bergelin, 2002). The introduction of a standardised method of measurement has been shown to be an effective way of reducing this variability (Burger et al, 1997; To et al, 2001; SMFM, 2016). For quality assurance and consistency, scans performed in the preterm surveillance clinic are undertaken by a core group of sonographers who are all accredited by the Cervical Length Education And Review (CLEAR) programme to minimise measurement discrepancies (CLEAR, 2017).

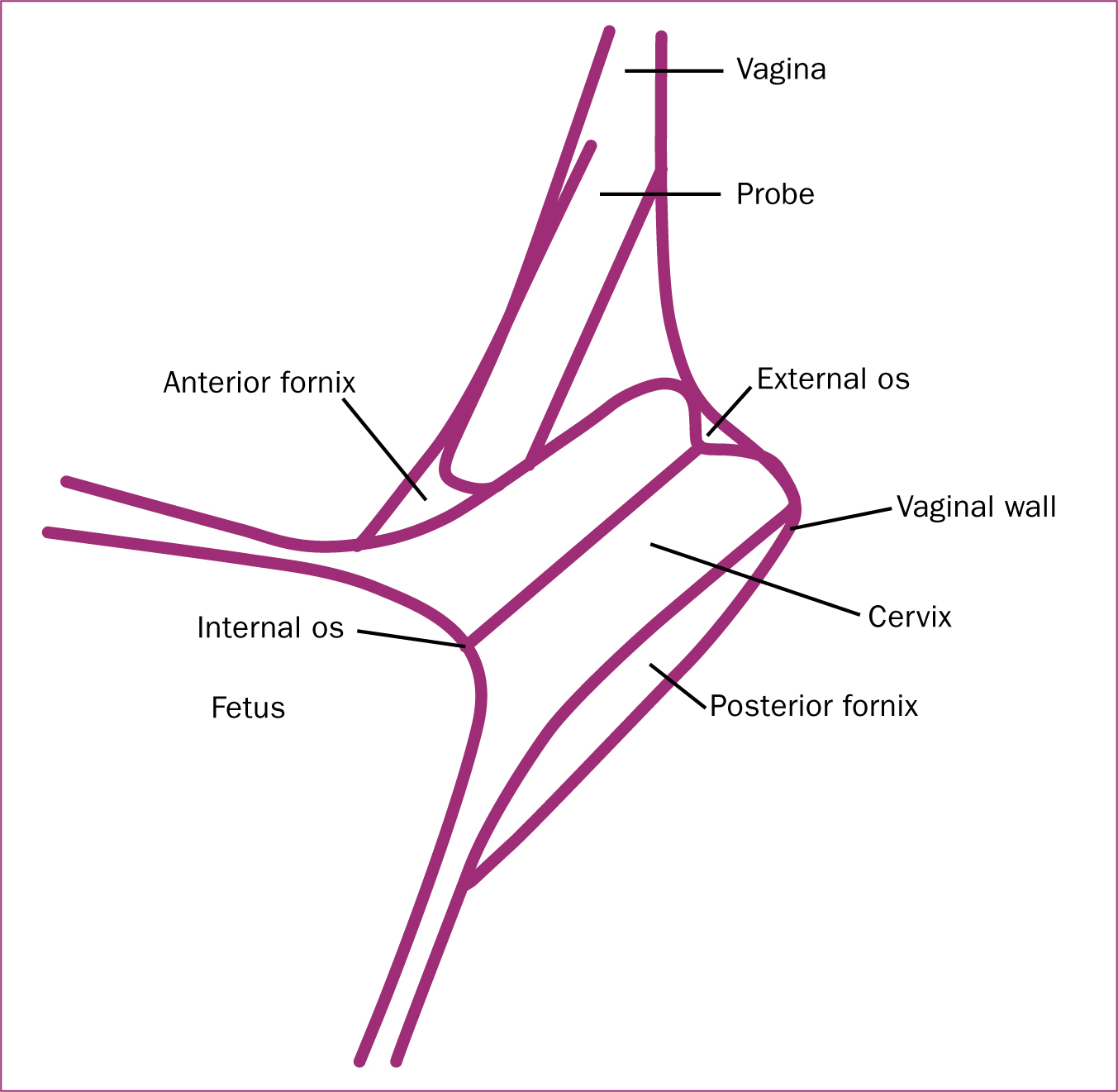

All scans are performed transvaginally with the maternal bladder empty, as a full bladder can artificially lengthen the cervix and cause compression of the lower segment, which mimics the appearance of funnelling (Mason, 1990). The cervix is imaged using the landmarks described by CLEAR (2017), which state that the cervix should occupy 75% of the image, the anterior and posterior walls of the cervix should be equal, and the image should clearly demonstrate the internal os, external os and cervical canal (Figures 2a–c). The cervix is a dynamic structure, and therefore at least three separate images and cervical length measurements are taken over a 2-3 minute period (Meijer-Hoogeveen et al, 2007). These images are acquired using minimal probe pressure to avoid artificially lengthening the cervix. Linear measurements are used to measure the cervical length, as they are more reproducible than spline measurements and a short cervix (less than 25 mm) will always be straight (To et al, 2001). To improve intra-operator variability, the cervix is re-measured until 3 measurements with no more than a 4 mm difference are obtained (Neale, 2011). For audit purposes, these images are saved to the Picture Archive Communication System. Reports note the shortest measurement meeting the image criteria, presence/absence of funnelling on application of supra pubic pressure and the presence of ‘sludge’ (Bujold et al, 2006). When funnelling is present, only the functional (closed) cervical length is reported. After 20 weeks, the best and shortest measurement meeting the image criteria is used to calculate the risk of preterm birth (Celik et al, 2008).

Management of women following ultrasound scans

Historically, women have attended every 2 weeks for cervical length assessment until 24 weeks gestation, as women who go on to have a preterm birth usually have cervical shortening during the second trimester of pregnancy. The rate of shortening is difficult to predict and reductions of between 0.5 mm and 8 mm have been reported (Society of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists of Canada, 2011). The challenge is to balance the likelihood of cervical shortening against cost and staffing. It was therefore deemed reasonable to assume an average rate of shortening of 5 mm per week and consequently reduce the number of visits for women with a longer cervix (greater than 35 mm), and no previous preterm loss or birth, to two cervical length assessments at 16-17 weeks and 20 weeks. In view of this, a medium-risk pathway has also been incorporated for women who have more than a 10 mm reduction in their cervical length measurement (a value that also allows for any inter-operator error), a cervical length measurement of 25-35 mm, or history of previous preterm birth, to have a fortnightly scan regime. The flowchart below summarises how women attending the clinic are managed (Figure 3).

The exception to the 25 mm cut-off are women who have had a trachelectomy, an operation where almost the entire cervix is removed due to cervical cancer. These women will have a short cervix due to their surgery and already have a cervical suture in place; therefore, changes in scan findings, rather than a cervical length of less than 25 mm, will initiate a same-day medical review.

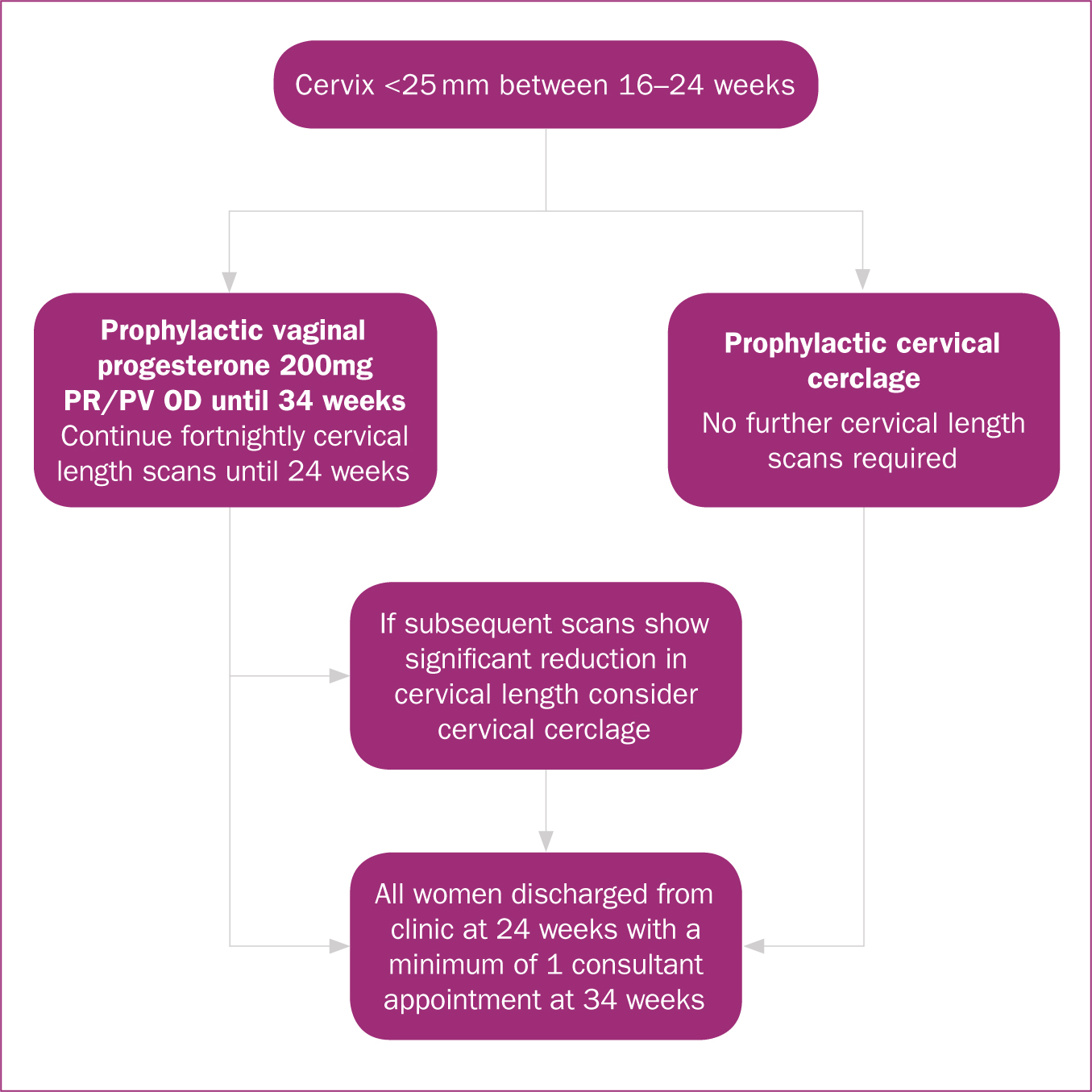

Management of a short cervix

NICE recommends that women should be offered a choice of either prophylactic vaginal progesterone or prophylactic cervical cerclage if they have a history of spontaneous preterm birth or mid-trimester loss between 16+0 and 34+0 weeks of pregnancy. Women should also be offered a transvaginal ultrasound scan between 16+0 and 24+0 weeks of their pregnancy if they have been shown to have a cervical length of less than 25 mm (NICE, 2015).

An Arabin pessary (a rubber ring that is inserted transvaginally around the cervix) is an alternative treatment that has been explored by one randomised controlled trial (Hezelgrave et al, 2016), where the investigators measured its ability to prevent preterm birth for women with a short cervix. This trial showed a statistically significant reduction in preterm birth before 34 weeks: 6% for the pessary group compared to 27% for the control group (Hezelgrave et al, 2016). In 2013, a Cochrane review concluded that there was still insufficient evidence to support the use of Arabin pessaries and further randomised controlled trials were required (Abdel-Aleem et al, 2013). Expert opinion on the use of Arabin pessaries remains divided, and we have chosen to exclude them from our management options.

Women who have a proven short cervix (less than 25 mm) and who attend the clinic between 16–24 weeks gestation are counselled as per the NICE guidelines. Health professionals at the clinic try to be open with women during their counselling and explain that a short cervix increases their risk of preterm birth, but that more than 50% of women with a short cervix will go on to have a term birth (Celik et al, 2008). Evidence suggests that the best way of preventing preterm birth for women with a cervical length of less than 15 mm is cervical cerclage (Owen et al, 2009) and clinicians are careful to ensure that women understand that neither cervical cerclage nor the progesterone pessary will eliminate the risk of preterm birth. The small risks associated with the insertion of a cervical cerclage (namely intra-operative bladder damage, cervical trauma, membrane rupture or bleeding) are also explained to women (NICE, 2015). Figure 4 summarises management of the short cervix.

Advice given to women

Women are given lifestyle advice based upon their risk of preterm birth. Women who are having prophylactic treatment, are at high-risk, or have a borderline cervical length measurement (near 25 mm cut-off) are reminded of the importance of a healthy diet and advised to refrain from high-impact exercise, such as running (swimming and walking are not considered high-impact) for the remainder of their pregnancy, as per NICE guidelines (2015). Women who fit this criteria are also advised to stop smoking if applicable and to refrain from sexual intercourse (until after 24 weeks gestation), douching and standing for long periods.

Assessment after 24 weeks

Cervical assessment is not carried out beyond 24 weeks gestation as cervical shortening at later gestations is less predictive of preterm birth (Honest et al, 2003). All women are therefore discharged from the preterm surveillance clinic at 24 weeks, with a further consultant antenatal clinic review arranged between 28-34 weeks.

Monitoring the service

Plans are in place to peer-review all images (using the CLEAR image criteria) and the corresponding reports after the initial 3 months. This is an important aspect of ensuring consistency throughout the clinic, particularly as ultrasound is an operator-dependent imaging modality and discrepancies in cervical length measurements could potentially have a significant effect on patient management and pregnancy outcomes. This is in keeping with the views of the Royal College of Radiologists (RCR) and the British Medical Ultrasound Society (BMUS), who recognise the need for peer review in maintaining standards of imaging and creating a learning environment (BMUS, 2014; RCR, 2014).

Since the introduction of the new clinic there has been a four-fold increase in the number of referrals for surveillance from 17 women in January-March 2017, to 42 women in June-August 2017. This appears to be a direct result of the new notification of pregnancy form. It is anticipated that the clinic has had a positive impact on preterm birth rates as a direct result of improving clinicians' ability to identify at-risk women and women with cervical shortening. This will be evaluated quantitively by comparing the preterm birth rate and obstetric outcome the year before (May 2016–April 2017) and after (May 2017–April 2018) the introduction of the clinic. This should provide a large enough sample size to generate statistically reliable results, given that there were 5688 births in 2016, including 381 preterm deliveries (preterm birth rate=6.7%). After discussion with other centres, a 25% reduction in the number of preterm deliveries has been estimated, leading to a minimum required sample size of approximately 3000 women (P=0.05, power 80%). In addition, the notes of women who gave birth to preterm infants since the introduction of the clinic will be reviewed to establish whether they had any unidentified risk factors. The inclusion criteria for screening will also be reviewed annually to incorporate any new literature and/or guidelines available. This is particularly important for the cervical trauma group, as debate remains over whether these women require cervical length screening (SMFM, 2016). Anecdotally, there appears to have been an improvement in women's experiences of surveillance due to increased woman-centred, consistent and cohesive care; this will be formally assessed by asking women attending the clinic to complete a questionnaire about their experiences. This questionnaire will be developed with the patient experience department and will include multiple choice questions that can be quantitively analysed and open-ended questions that can be qualitatively assessed for recurring themes.

Conclusions

Preterm birth is a major challenge facing modern obstetrics, with rising incidence despite prevention and treatment. Cervical shortening in the second trimester can cause preterm birth, and effectively identifying women with risk factors between 16-24 weeks gestation is key to reducing the preterm birth rate. It is hoped that this article has demonstrated the advantages of establishing a dedicated preterm surveillance clinic as a means of achieving this aim.