Newly qualified midwives are expected to function as autonomous practitioners (Nursing and Midwifery Council (NMC), 2004) from their date of registration, yet it was apparent locally that there was a mismatch between this expectation and the reality of practice. The newly qualified midwife is expected to be competent in undertaking a full caseload (NMC, 2009), performing holistic care while developing and remaining autonomous and responsible for his/her own actions (NMC, 2012). The focus of competence in ‘low risk’ and ‘normality’ has been championed once more through the Birth Place study (Brocklehurst et al, 2011; Schroeder et al, 2014) and the forthcoming publication of updated National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) guidance related to promoting birth in midwifery-led units or at home for low-risk women. Carter et al (2013) assert that for newly qualified midwives to practice autonomously, they require well-developed critical thinking, covering the increasing complexity within more high risk environments. There is a need for educators to develop curricula that address the development of complex care skills during training to meet this changing acuity (Hughes and Fraser, 2011; Skirton et al, 2012; Avis et al, 2013; Carter et al, 2013; Fullerton et al, 2013; Schytt and Waldenström, 2013). This will have an impact on the newly qualified midwives' changing responsibility and confidence to practise autonomously.

Newly qualified midwives are presented with a variety of challenges as they enter their first post and work across hospital and community settings. Studies have suggested that these challenges affect the ability to adopt and effectively use different models of care depending on client need and location (e.g. obstetric unit, home, or midwifery-led unit) and the values and perspectives of the teams with whom they are working (Begley, 2002; Hunter, 2004; van der Putten, 2008; Fenwick et al, 2012). These uncertainties are likely to make this a period of rapid learning and pressure for the newly qualified midwife. At the same time as they negotiate this maze and determine their place in an already established culture (Fraser, 2006; Hobbs, 2012; Avis et al, 2013), newly qualified midwives need to identify a niche in which they belong. While much has been written about transition and reality shock and, more recently, the transition for newly qualified midwives (Begley, 2001a; Begley, 2001b; Begley, 2002; Montgomery et al, 2004; van der Putten, 2008; Hughes et al, 2002; Fenwick et al, 2012; Hobbs, 2012), the reality of the newly qualified midwives' situation can result in a lifestyle shock (Kramer, 1974; Maben and Clark, 1996; Godinez et al, 1999; Clark and Holmes, 2007; Newton and McKenna, 2007), which may contribute to the attrition of between 5 and 10% of newly qualified midwives within a year of graduating (Royal College of Midwives (RCM), 2010).

Commissioned places for student midwives have increased since 2002 supporting governmental initiatives to increase the numbers of midwives to deal with the rising birth rate coupled with projections of large numbers of retiring midwives (Centre for Workforce Intelligence (CfWI), 2012). Retirement creates particular problems for the support of newly qualified midwives as a result of lost knowledge and experience (Gerrish, 2000) and the ability to provide preceptors for newly qualified midwives. More women over the age of 40 years, or with pre-existing health/social issues are experiencing complex pregnancies and births, resulting in newly qualified midwives caring for women from a wider risk profile (Department of Health (DH), 2010a). The rising birth rate, increased risk profile and the projected diminishing levels of experienced midwives are likely to have an impact on the confidence levels of newly qualified midwives' leading to uncertainty as to their choice of career (Gerrish, 2000). Demographic and workforce changes and locally-voiced contradictions in expectations, increases the importance of understanding better the experiences of the newly qualified midwife with a view to improving the period of transition from student to graduate practitioner. Good practice ensures that newly qualified midwives are offered preceptorship programmes to aid transition to their new role (NMC, 2008; DH, 2010b; NMC, 2011; Hughes and Fraser, 2011; NMC, 2012). However, there may be a perception that senior midwives expect newly qualified midwives to rapidly develop competence across the spectrum of risk now usual within UK maternity services in order to work in the delivery suite within weeks of qualifying.

Aim

The aim of this study was to elicit the lived experience of newly qualified midwives from the point of registration to 12 months post-registration.

Design

Interpretive phenomenology was used to understand the experience of being a newly qualified midwife in the NHS while respecting the integrity of the participants. Van Manen's (1990;1997) perspective of interpretive phenomenology was chosen to explain the interpretations that have already been made by those who have undergone the experience (Jackson, 2005) and to describe accurately the experience of the phenomenon under study, being careful neither to generate theories or models, nor to develop general explanations (Field and Morse, 1990).

Ethical approval from the University School's ethics committee was granted and managerial agreement was given to access the sample of final-year student midwives.

Participants

Recruitment to the study was indirect and mediated by the cohort tutor. All 15 pre-registration student midwives from the first cohort of a new curriculum due to graduate were informed about the study. After the initial contact, students were asked to respond directly to the researcher if they wished to participate. Once a student had contacted the researcher an appointment was arranged to ensure their full understanding of the study and a consent form was completed. Twelve students, who gained first posts across a number of NHS Trusts, volunteered and remained for the duration of the study. This sample size was as expected to draw conclusions for this cohort. Participants were all female, aged 18 to 45 years, and from different ethnic, social and cultural backgrounds (Table 1).

| Pseudonym | Age at first interview (years) | Work experience prior to midwifery training | Previous educational experience prior to midwifery training | Position at Interview 1 | Position at Interview 2 | Position at Interview 3 | Amount of time in practice by end of data collection |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alicia | 23 | Part-time jobs as receptionist and carer | Geography degree | Waiting for interview | Case-loading team | Remained in first post | 1.0 WTE for 10.5 months |

| Ashleigh | 33 | Maternity care assistant at a birth centre | Access course | Awaiting first post | Integrated team | Remained in first post | 0.8 WTE for 11.5 months |

| Claire | 38 | Occupational therapist assistant (13 years) | Access course | Awaiting first post | Integrated team | Remained in first post | 0.8 WTE for 11.5 months |

| Edith | 25 | Lab technician in an HIV research lab | BSc Biomedical Science | Awaiting first post | Hospital midwife (4 weeks) left post prior to interview | Commenced second post at different maternity unit | 1.0 WTE for a total of 4 months |

| Jade | 25 | Marketing work and graphic designer | English degree | Waiting for interview | Integrated team | Left midwifery profession | 0.8 WTE for 6 months |

| Martha | 27 | Lifeguard/swimming coach, exercising and breaking ponies, waitress/barmaid, cashier, animal care assistant and worked in a day nursery with babies | Biology degree | Awaiting first post | Integrated team | Remained in first post | 0.8 WTE for 11.5 months |

| Naomi | 22 | College work | Pre-degree diploma | Awaiting first post | Case-loading team | Remained in first post | 0.8 WTE for 11.5 months |

| Sally | 38 | Mortgage advisor and bank care assistant | College undertook Maths and English GCSE and Access course | Awaiting first post | Integrated team | Remained in first post | 0.6 WTE for 11.5 months |

| Sam | 26 | Dental nurse | Dental nurse training and BTEC national diploma | Awaiting first post | Hospital team midwife | Remained in first post | 0.8 WTE for 11.5 months |

| Sarah | 25 | Part-time in a clothes store | Studied social psychology at University so had A-Levels | Waiting for interview | Integrated team | Remained in first post | 0.8 WTE for 11.5 months |

| Valerie | 35 | Food production | Access course | Awaiting first post | Waiting for first post | Hospital midwife delivery suite | 1.0 WTE for 7.5 months |

| Vivienne | 22 | Worked in vet practice for 10 years | A-levels | Awaiting first post | Case-loading team | Remained in first post | 1.0 WTE for 11.5 months |

WTE—whole time equivalent post; BSc—Bachelor of Science; BTEC—Business and Education Council

Data collection

Participants were based at one higher educational institution at the point of recruitment. Reflexivity aided trustworthiness of the research process, by encouraging the researcher, who is also a lecturer, to ‘come clean’ about knowledge claims, personal experiences and the social context that may affect the research process (Finlay, 2002; Gough, 2003; Maso, 2003). Therefore, it was anticipated that participants would not feel obliged to participate.

Semi-structured interviews were used. Each participant was interviewed three times during their first year after registration. The initial interview took place on the University campus, while the participant was still a student but at the point of qualification. The two follow-up interviews at 4 and 12 months postgraduation were undertaken at a venue agreed with the participant and did not infringe on the participants’ employment or employer.

An interview schedule with prompt statements was piloted and used to ensure the same opening format was used for each participant at the relevant interview, i.e. ‘tell me what you expect being a qualified practising midwife will be like’ (first interview) and ‘tell me about the realities of working as a practising qualified midwife’ (second and third interviews). The semi-structured faceto-face interviews, lasting between 30 and 60 minutes, then developed from comments made by each participant (Kvale, 2007). All three interviews were digitally recorded and transcribed verbatim. To ensure confidentiality each participant was referred to by a self-selected pseudonym during the interviews and in the subsequent analysis.

Data analysis

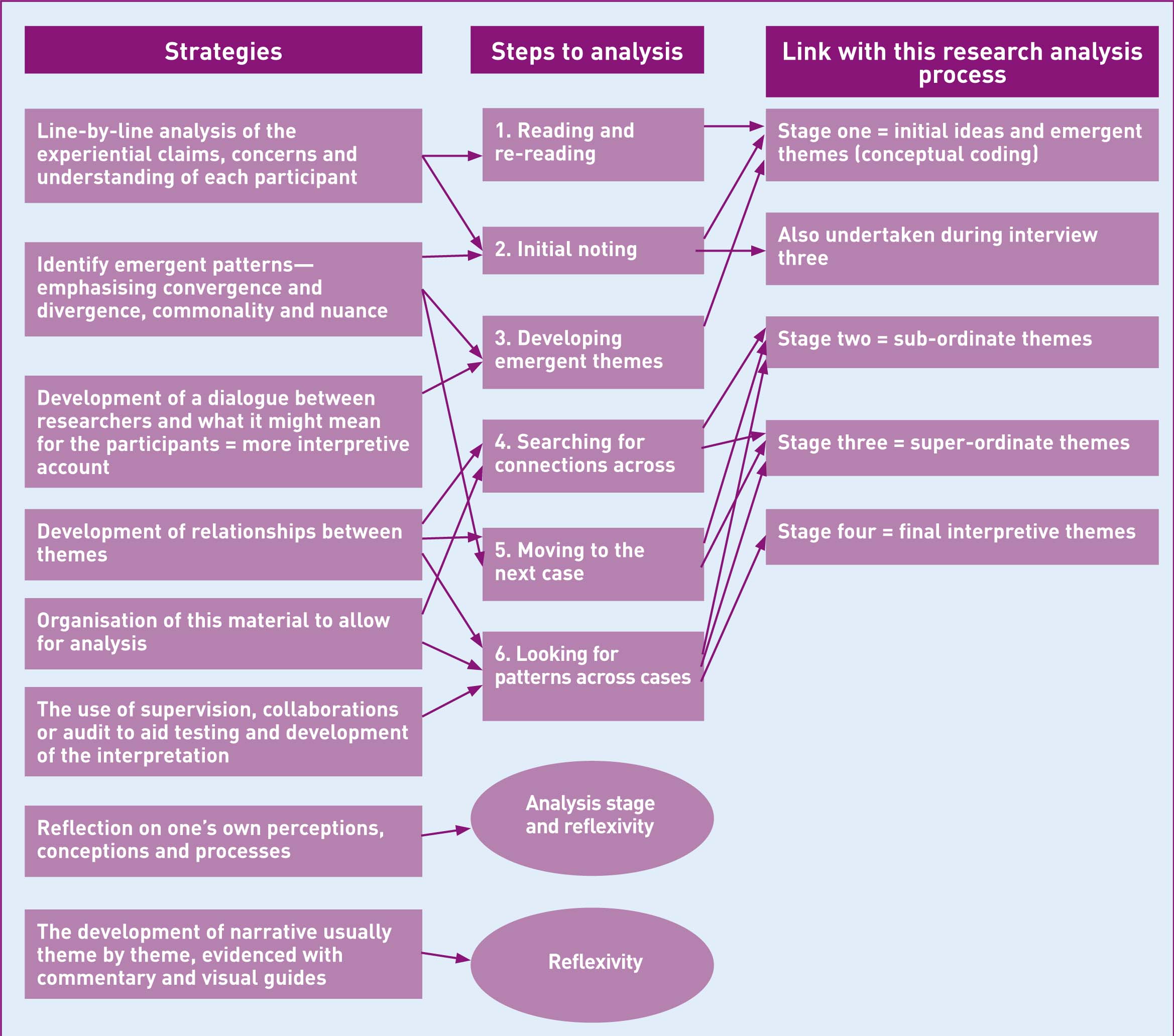

Smith et al's (2009) interpretive phenomenological analysis (IPA) was used (Figure 1). Initially, 263 sub-ordinate themes emerged; these were eventually reduced to six super-ordinate themes. These super-ordinate themes were reviewed and reduced to two final interpretive themes which constituted becoming a midwife (Table 2).

| Sub-ordinate themes | Super-ordinate themes | Final interpretive themes |

|---|---|---|

| Place of work; expectation; experience; work–life balance; tired; realities of role; support/preceptorship/supernumery; conflicting information about job; learning; preparation for role | False promises | Fairy tale midwifery—fact or fiction |

| Workload; inter-professional working; team working; philosophies of care; organization and staffing; midwifery skills and resources; on my own | Reality shock | |

| Autonomy/advocacy/responsibility; decision-making; delivery suite versus community | Beyond competence; part of the club | Submissive empowerment—between a rock and a hard place |

| Belonging/being valued; culture mentorship; developing practice; asking questions; leaving/returning | Self-doubt | |

| Self-belief/attitude; anxiety; negative feelings; feelings of role; positive feelings | Struggling |

Rigour

Two research supervisors independently checked the transcriptions with the emergent themes instead of returning the data to the participants for member checking. Little disagreement was found and when it did occur, discussion and clarification ensued. On completion of the analysis, the completed interpretation was returned to the participants to see if they could recognise themselves in it: all 12 confirmed that they could.

Results and Discussion

Becoming a midwife

The collective experiences of the 12 participants during their first 12 post-registration months of ‘becoming a midwife’ were akin to coming of age or

‘…passing your test when you’ve just learnt to drive and then you’re out and you could really begin to learn and kind of consolidate your learning from being a student…’ [Claire 1].

This period for consolidation was typically looked forward to by the newly qualifying students, as Ashleigh highlights:

‘… when I was working on the wards for the last few weeks, um I, I definitely thought I’m ready and I can do this …’ [Ashleigh 1].

It heralded, for most, the start of a new phase where they recognised that they were

‘… a midwife now’ [Martha 2].

For all but one, this happened within a few months of qualifying, but Jade never felt that she achieved this and she left midwifery.

Participants' experiences of becoming a midwife are clustered under two final interpretive themes, ‘fairy tale midwifery—fact or fiction’ and ‘submissive empowerment—between a rock and a hard place’, each showing the tension between the reality and their ideal of becoming a midwife. This tension was exemplified through experiences relating to ‘false promises’, ‘reality shock’, being (or not) ‘part of the club’, ‘self-doubt’, ‘struggling’ and feeling ‘beyond competence’. The newly qualified midwives felt devoid of autonomy and responsibility and experienced high levels of anxiety as they progressed during their first year of practice, thus adding a fourth stage to Holland's (1999) three stages of transition.

Fairy tale midwifery—fact or fiction

False promises and reality shock

Participants, as students, at the inception of their midwifery career had an idealistic perception of the role of a midwife, the work that they would be expected to do and the relationships that they would have with others. Once qualified, the reality of midwifery failed to measure up to their ideals and self-made expectations (Kramer, 1974). In effect they experienced, what Pearce (1953) referred to as a theft by deceit or by false promises. In Pearce's work the false promises were made by others, in this research they were not only made by others, but were self-inflicted by the participants as they constructed their imaginary expectations; their ‘fairy tale of midwifery’. As they qualified and began to practise they experienced the reality of midwifery (the fact) rather than their idealised fiction. Their fairy tale was shattered or stolen by reality and created as a result a reality shock.

‘…It's awful, it's a lot harder than I expected it to be…I didn't realise how difficult that would be…yeah I think it's been a really bad experience’ [Edith 2].

At the point of registration, participants expressed the belief that their training and experiences of caseload held practice, community, birth centre and hospital focused care provision had prepared them well for their post as a qualified midwife, similar to the findings of Maben and Clark's (1996) newly qualified nurses. However, as time since qualification elapsed, they became more sceptical about the preparation that they had received. At 4 months post-registration the newly qualified midwives considered that their training had not fully equipped them for the real world of clinical practice, not unlike Newton and McKenna (2007) and van der Putten's (2008) findings. University education was portrayed as idealistic by participants; as students they were protected by:

At the point of registration, participants expressed the belief that their training and experiences of caseload held practice, community, birth centre and hospital focused care provision had prepared them well for their post as a qualified midwife, similar to the findings of Maben and Clark's (1996) newly qualified nurses. However, as time since qualification elapsed, they became more sceptical about the preparation that they had received. At 4 months post-registration the newly qualified midwives considered that their training had not fully equipped them for the real world of clinical practice, not unlike Newton and McKenna (2007) and van der Putten's (2008) findings. University education was portrayed as idealistic by participants; as students they were protected by:

‘the shelter of the university’ [Ashleigh 1]

and that

‘nothing can prepare you for the realities’ [Valerie 3].

While supernumerary and preceptorship periods were offered, dependent on staffing levels and workloads, to ameliorate this reality shock these were not seen as valuable or fully understood by participants. Midwifery 2020 (DH, 2010a) cites the flying start programme (NHE Education for Scotland, 2010) as good practice and could alleviate some of the anxieties of the newly qualified midwife. Long shifts and long stretches of working consecutive days led to extreme tiredness leaving them feeling:

‘frustrated’ [Edith 2]

and

‘stressed’ [Naomi 3],

and sometimes alone, as the only qualified midwife, at work. They found it hard to

‘switch off’ [Jade 3]

from their work, often worrying that they had omitted something important or that they had done something wrong.

Submissive empowerment—between a rock and a hard place

Struggling and self-doubt

Workload and accompanying support were important issues for all participants. For those working community shifts and being called in to cover hospital shifts, no consideration was given to the work they had still to complete in either setting. This served to erode confidence and diminished their ability to consolidate their knowledge and skills in one particular area before moving to another. It meant that some participants viewed working in the community as a:

‘shambles [and] rubbish’ [Ashleigh 3].

Working in the hospital was also perceived as traumatic, but for different reasons. Participants were expected, within the first few weeks of qualifying, to be the only qualified midwife in a busy high-risk ward area assuming responsibility for 25 to 30 women and their babies. This had a dual effect; it created a heightened level of anxiety accompanied by, more positively, a steep learning curve. In this situation, support was more easily available than in the community by telephone to the delivery suite or duty manager. Despite these perceived increased levels of anxiety, participants preferred to work within the hospital setting than in the community.

Being part of the club

Participants were uncomfortable in the knowledge that their ideal was not the reality they were experiencing. To ‘survive’, they quickly had to submit to the realities of midwifery. To do this they felt that they had to pass through an initiation period before being accepted by their more experienced colleagues.

At 4 months, this transition manifested itself in several ways with participants telling of the perceived need to impress their delivery suite senior colleagues, even when they had been unkind to them, in order to feel that they ‘belonged’ and were accepted. Participants had to learn how to deal with their colleagues’ idiosyncratic behaviours when

‘some people when it's busy aren't as helpful and some people are always helpful’ [Naomi 2].

The newly qualified midwives in this study were expected to go above and beyond to ensure that they were not perceived as lazy, despite their own perception of some of their more experienced colleagues as being so. The participants’ working worlds often seemed to revolve around others’ moods or their perceptions of their characters; if the delivery suite coordinator was nice, participants felt positive in their work and had an increased level of morale. They began to know who to ask if they were unsure about what to do and who to avoid. Intimidation was linked to senior midwives with one participant excusing this behaviour as a result of the stresses of being responsible for managing busy delivery suites.

Beyond competence

Responsibility remained the participants' biggest cause of anxiety. The realisation that

‘the amount of responsibility that you now have is just completely yours’ [Jade 2]

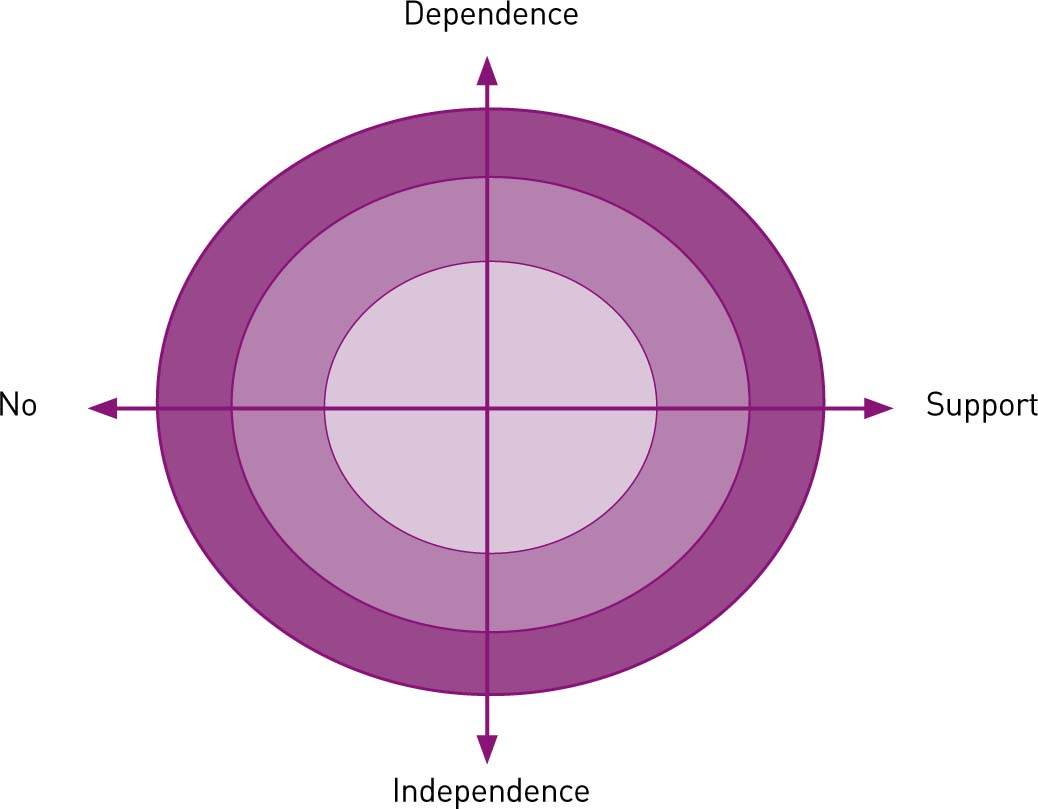

was not fully appreciated until they had commenced their first post. Despite being taught about responsibility, accountability and autonomy as students, participants did not believe they were accountable or autonomous at any stage during their first 12 post-registration months. Decision-making was seen to be controlled by the delivery suite coordinators and/or the obstetric team. Participants did not feel valued or trusted in decision-making and they perceived they were required to carry out preordained instructions for their labouring clients. Consequently, at 12 months participants stated that they had less confidence in their decision-making abilities than at the outset of this research. They did not acknowledge that they had begun to make more decisions themselves or that they were moving from being a novice to being a more competent, confident, advanced practitioner (Benner, 1984). The expectation to take responsibility for overseeing junior students while consolidating their own training was difficult, especially when it occurred within the first month of employment. Asking very newly qualified midwives to take on this responsibility led to increased anxiety and frustration, which undermined their time for their own preceptorship and support. Findings share commonality with aspects from Hughes and Fraser (2011) and Avis et al (2013). Skar (2010) considers the ‘authority’ and ‘freedom’ to make decisions and act in accordance with self-knowledge as being autonomous in practice. In the case of these participants, they may have a work role that enables autonomy, but perceive a lack of personal autonomy hence they chose not to exercise the freedom to perform autonomously. This could be due to a lack of support from peers, preceptors, managers or the institution as a whole, which causes a pendulous swing between dependence and independence. It may be that participants perceive that they have personal autonomy and have the confidence to exercise it, but in the context of the institution, they are prevented from doing so leading to a loss of autonomy (Figure 2).

At the end of the year, participants were generally proud of their achievements, but the role was not as they had expected it to be. They had seen a change in themselves over the year in terms of confidence, although they had struggled throughout the 12 months to perform their role to the best of their abilities.

Participants had reflected on their experiences by the second and third interviews, with four participants stating that they could not wait until the third interview so they could tell what had happened to them. This means that they had already applied an interpretation to their own experience, which could be viewed as a potential flaw in the theory that suggested that participants would not do this.

Conclusion

This study has highlighted the challenges some newly qualified midwives face with changing levels of professional responsibility. At the point of registration, the participants of this study perceive an achievement of both autonomy and support, but the reality is that they attain one or the other dependent on where they practise. The implication for practice is how the newly qualified midwives can achieve both. Newly qualified midwives may still be in ‘student mode’ and expect both autonomy and support rather than seek it out, this is dependent on the curriculum and how prepared the students are during their programme. Further research could consider if this is the same for all newly qualified midwives.