Background

Gestational diabetes mellitus (GDM) is defined as glucose intolerance first identified in pregnancy that resolves postpartum (Basri et al, 2018). It has an increasing prevalence worldwide and is associated with potentially serious complications for both mother and baby (Metzger et al, 2008; Galtier, 2010). Fundamental to the management of GDM is controlling blood glucose levels, with elevated levels of hyperglycaemia suggested as the mechanism that causes increased risk of adverse maternal and infant outcomes (Lowe et al, 2012).

Management of GDM includes lifestyle interventions and pharmacological therapy. Lifestyle interventions (including as a minimum healthy eating, physical activity and self-monitoring of blood glucose concentrations) are the only interventions that have reported health improvements for maternal and fetal outcomes (Martis et al, 2018).

There is growing evidence surrounding the benefits of physical activity amongst women with GDM. Meta-analyses of physical activity and exercise interventions have shown improvements in glycaemic control and reduced insulin requirements (Harrison et al, 2016; Cremona et al, 2018; Hillyard et al, 2018). Other benefits include improved cardiovascular fitness, mental wellbeing and prevention of hypertensive disorders (Mottola et al, 2018; Dipietro et al, 2019). It is recommended by the UK chief medical officer physical activity guidelines (Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists, 2017) that women undertake at least 150 minutes of aerobic physical activity and perform muscle strengthening activities twice per week throughout pregnancy (Mottola et al, 2018; Dipietro et al, 2019). Despite this, a report found at least 65% of women with GDM are not meeting recommendations (Galliano et al, 2019). Common reported barriers are fatigue, lack of time and pregnancy discomfort. Frequent enablers include maternal and fetal health benefits, social support and pregnancy-specific programs (Harrison et al, 2018). It has been highlighted that women with GDM require clear, simple and specific messages to feel confident and safe about being physically active (Harrison et al, 2019). However, time allocation and resources compete with other components of care, and many inactive women forgo the benefits of physical activity.

Integral to physical activity interventions are behaviour change techniques (BCTs), particularly those that are person-centred, addressing specific barriers and enablers (Harrison et al, 2018). They have been shown to reduce the decline of physical activity during pregnancy (Currie et al, 2013). Motivational interviewing uses a number of BCTs that have been shown to improve physical activity levels in those with chronic disease (O'Halloran et al, 2014). However, no studies have examined a physical activity-specific motivational interviewing intervention in women with GDM. Motivational interviewing is designed to strengthen personal motivation and commitment to individualised goals by eliciting and exploring the person's own reasons for change within an atmosphere of acceptance and compassion (Miller and Rollnick, 2013). Women with GDM are a potentially motivated group seeking to optimise their health and glycaemic control over a short period of time who may respond to physical activity motivational interviewing. In this quality improvement project, motivational interviewing was incorporated into routine clinical care for women with GDM. The study evaluated the impact of this approach on self-reported physical activity levels 2 weeks after motivational interviewing.

Methods

This study was a service evaluation of a quality improvement project to introduce motivational interviewing into routine care, with the aim of increasing physical activity in women with a diagnosis of GDM.

Women attending a weekly GDM clinic at the Women's Centre of the Oxford University Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust between May 2018 and June 2019, with a confirmed diagnosis of GDM as defined by the International Association of Diabetes and Pregnancy Study Groups recommendations (Metzger et al, 2010) and with no contraindications to physical activity as per the internationally recognised Canadian guidelines (Mottola et al, 2018) were invited to enrol.

Data collection

Participants were invited to a 20-minute individual motivational interview on physical activity, in addition to their routine care appointments. Verbal consent was obtained to participate in the interview. The motivational interview took place at their initial hospital appointment following a diagnosis of GDM. This was delivered by a trained healthcare professional (midwife or doctor).

Each healthcare professional delivering the motivational interview had completed a certificated 2-day training course and 8 hours of supervised training sessions. The intervention was delivered using a framework, where motivational interviewing micro skills (open-ended questions, affirmations, reflections and summaries) were used in all sessions to progress participants through the processes of change (engagement, focusing, evocation, and planning) (Miller and Rollnick, 2013). The session included person-centred goal setting, activity planning and specific information about the benefits and types of suggested physical activity. Table 1 outlines the structure of the motivational interviewing delivered with BCTs.

Table 1. Structure of the motivational interview

| Part | Details | Behaviour changes techniques* |

|---|---|---|

| 1. Setting the scene, agreeing the agenda | (i) Establish empathy, rapport and ‘goal congruence’ from start. (ii) Manage some expectations of consultation. (iii) Give person a sense of control over the conversation and agree the main focus of the conversation | |

| 2. Exploring a typical day | (i) Demonstrate understanding of a particular aspect of patient's life, where activity fits into life. (ii) Demonstrate non-judgemental, person-centred listening skills. (iii) Listen for any ‘change-talk’ indicating that the patient is thinking about change, wants to change, is able to change, has already started to make some changes. (iv) Help them feel heard and understood | |

| 3. Exploring importance | (i) Explore the importance of activity and reasons for changing their activity levels. (ii) Help the person give voice to and better understand their own reasons for changing. (iii) Elicit and develop change talk. (iv) Strengthen the other persons readiness to change | Prompt and cues (7.1) |

| 4. Sharing information on benefits | Ask–Share–Ask for information about the benefits of physical activity specifically for gestational diabetes | Information about Health Consequence (5.1)Credible source (9.1) |

| 5. Sharing specific information/knowledge about activity | Ask–Share–Ask for information about the type, duration and expectations of physical activity specifically for gestational diabetes and address barriers | Information about Health Consequence (5.1)Instruction on how to perform behaviour (4.1)Credible source (9.1) |

| 6. Exploring and building confidence | (i) Strengthen self-efficacy for change. (ii) Elicit and develop change talk. (iii) Share what other people have found helpful when making a change, such as glucose control (using Ask–Share–Ask) | Prompt and cues (7.1)Focus on past success (15.3) |

| 7. Sharing information about building confidence | (i) Ask–Share–Ask for information about increasing confidence to become more active. (ii) Provide suggestions, increase readiness | Valued self-identity (13.4)Social comparison (6.2) |

| 9. The key question | Help the person decide what to do next | Problem solving (1.2) |

| 10. Exploring options | (i) Generate a range of possible ways forward. (ii) Build optimism and confidence that change is possible, encourage autonomy and personal decision making, share some of your experience and expertise about what might be helpful. (iii) Make progress towards agreeing the way forwards | Social support (3.1) |

| 11. Agreeing a plan and goal setting | (i) Help the person generate a plan for their future. (ii) Help evoke ideas. (iii) Complete personal goal setting tool | Goal setting (behaviour) (1.1)Action planning (1.4) |

| 12. Relapse prevention | (i) Help the person explore how life might be different if they decide to (and are able to) change, compared to if they did not. (ii) Help the person better understand risks of not changing and benefits of changing, without having to tell them. (iii) ‘Develop discrepancy’ between current behaviour and desired future behaviour. (iv) Learn more about person's hopes, plans and values. (v) Build hope, elicit and develop change talk. (vi) Agree on need for and timing of future conversations. (vii) Agree on medium and location of future conversations (face-to-face, telephone) | Comparative imaging of future outcome (9.3)Verbal persuasion about capability (15.1)Commitment (1.9) |

| 13. Support | Explain the support offered | Social Support (3.1) |

A telephone consultation was undertaken 2 weeks after the initial motivational interview to help build self-efficacy, assess progress against their own goals and review physical activity levels.

Self-reported physical activity levels were used as the outcome measure. A modified version of the Exercise Vital Sign (EVS) (Coleman et al, 2012) was used to evaluate baseline self-reported physical activity of moderate intensity or greater. The EVS consists of two questions:

- On average, how many days per week do you engage in moderate intensity or greater physical activity (like a brisk walk) lasting at least 10 minutes?

- On those days, how many minutes do you engage in activity at this level?

The introductory text of the EVS was modified by the authors to make the introduction relevant to pregnant women. The EVS was recorded at the initial motivational interview appointment and at the 2-week telephone appointment. Total weekly aerobic activity was calculated. This tool was chosen as it is simple and time-efficient to use. When entered in the electronic patient record system, it automatically calculates and documents the weekly physical activity level and their activity category.

To aid interpretation and explanation to the participants, activity levels were coded in a traffic light system, with three categories, red, amber and green, based on minutes of moderate intensity physical activity completed per week (MIPA/week). Red was defined as <30 MIPA/week, amber as 30–149 MIPA/week and green as ≥150 MIPA/week. These categories were chosen with reference to the most recent physical activity guidelines recommending 150 minutes of moderate intensity physical activity/week (Galliano et al, 2019; Harrison et al, 2018; 2019). The specific categories were adopted from the activity classification used in the Health Survey for England (NHS Digital, 2017).

Data analysis

Data were analysed using Microsoft Excel (version 16.29). A paired t-test was used to compare self-reported physical activity before and after the motivational interview. A Pearson's Chi-squared test was used to assess correlation and determine statistical significance between baseline and 2-week follow-up physical activity levels. Statistical significance was determined as <5% (P<0.05). Those without complete follow-up data were excluded from this analysis.

Incomplete datasets were excluded from the analyses. This included women who were not contactable or declined to participate in the 2-week follow-up telephone call

This quality improvement project was part of a service evaluation project to improve the standards of the care within the GDM service. It was registered with the Oxford University Hospital Trust Maternity Departmental Clinical Governance Committee

Results

A total of 100 motivational interviews were undertaken over the time period with baseline self-reported physical activity data and 2-week self-reported physical activity follow-up data obtained from 62 women. Of the 38 women where follow up data was not obtained, nine declined their consent for the follow-up telephone call, 23 did not answer the call, three accepted the call but did not want to discuss their physical activity levels at that time. Two women were admitted with complications of their pregnancy within the 2-week follow-up period (unrelated to physical activity), and one delivered her baby.

At baseline, the mean age of participants with completed follow-up data was 31.5 years (range: 21–43 years), mean gestation was 27 weeks+5 days (range: 9–36+4/40 weeks) and mean body mass index was 29.9kg/m2 (range: 18.3–48.2kg/m2).

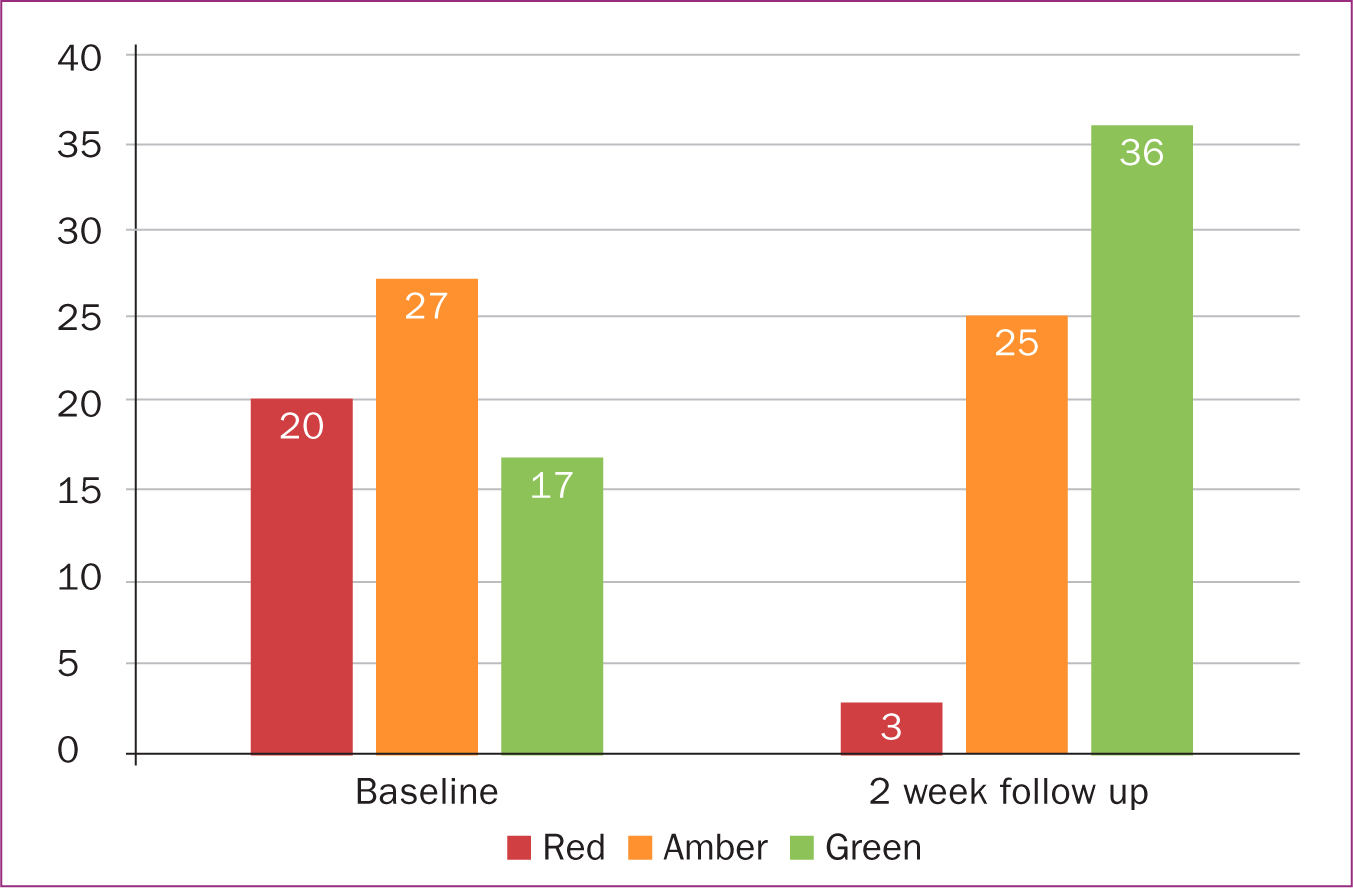

The self-reported physical activity levels at baseline and 2-week follow up are shown in Table 2. The classification of participants by level of physical activity per week is outlined in Table 3 and Figure 1. At baseline, the mean reported physical activity was 101.0 MIPA/week (standard deviation±100.1). Over one-fifth of participants (27%) reported at least 150 MIPA/week (green); 20 (31%) reported <30 MIPA/week (red) and 27 (42%) undertook 30–149 MIPA/week (amber).

Table 2. Self-reported moderate intensity physical activity levels at baseline (prior to motivational interview) and 2-week follow up.

| Total cohort physical activity | Average per individual (minutes/week) | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline | 6465 | 101.0 (standard deviation±100.1) | <0.001 |

| 2-week follow up | 11280 | 176.3 (standard deviation±130.49) |

Table 3. Modified EVS output for self-reported physical activity levels at baseline and 2-week follow up.

| Modified EVS output | P value | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Red | Amber | Green | ||

| Baseline | 20 (31.3%) | 27 (42.2%) | 17 (26.6%) | <0.0001 |

| 2-week follow up | 3 (4.7%) | 25 (39.1%) | 36 (56.3%) | |

Red: <30 minutes of moderate intensity physical activity per week

Amber: 30–149 minutes of moderate intensity physical activity per week

Green: ≥150 minutes of moderate intensity physical activity per week

Figure 1. Self-reported physical activity categories at baseline and 2-week follow-up

Figure 1. Self-reported physical activity categories at baseline and 2-week follow-up

Two weeks after the intervention, the mean physical activity was 176.3 MIPA/week (standard deviation±130.49). The majority of partcipants (56%) reported undertaking at least 150 MIPA/week, 3 (5%) reported undertaking <30 MIPA/week and 25 (39%) reported 30–149 MIPA/week. There was a significant association between the motivational interviewing intervention and increased weekly physical activity at two-week telephone follow-up (P<0.001)

Discussion

The incorporation of physical activity-orientated motivational interviewing into routine clinical care for women with GDM demonstrated encouraging results. Self-reported physical activity levels increased significantly at 2-week follow up. It appears women with GDM are receptive to this approach, with a mean increase in physical activity levels of 75 minutes/week, and more than half of the participants increasing their activity to meet physical activity guidelines (Mottola et al, 2018; Dipietro et al, 2019).

At baseline visit, only 27% of women attending the GDM service reported meeting the aerobic portion of the physical activity recommendations, in contrast to approximately 58% of all women aged 16 and over in England (NHS Digital, 2017). While it is acknowledged that activity levels decline during pregnancy (Borodulin et al, 2008), the post-motivational interview intervention figures were comparable to those of the general population (56% vs 58%).

Comparing studies examining activity levels in pregnancy, particularly in the third trimester, is difficult because of variations in recording methods and definitions. In most studies, physical activity is treated as a categorical variable, reported as a summary measure for the entire pregnancy or only reported in a single trimester (Bisson et al, 2016). Therefore, it is challenging to established typical or expected physical activity levels. Among those using a validated assessment in the third trimester, Harrod et al (2014) using the Pregnancy Physical Activity Questionnaire found 38% of 823 pregnant women met the previous American College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists guidelines (30 minutes of moderate activity on most days of the week) in late pregnancy, while Watson et al (2017) found a median level of moderate to vigorous physical activity of 16.6min/day among 85 women in the third trimester using hip accelerometery.

Relatively few studies have assessed physical activity levels specifically in women with GDM. An early report in 2006 conducted a postal survey of 28 women with GDM and found that only 39% were meeting exercise recommendations (Symons Downs and Ulbrecht, 2006). A more recent report found comparable findings in 2706 women with GDM (measured with the International Physical Activity Questionnaire). It reported that 26% were classified as inactive (0-10 minutes physical activity/week), 39.7% insufficiently active (11-149 minutes physical activity/week) and 34.3% active (>150 minutes physical activity/week) during pregnancy (Galliano et al, 2019). This is similar to the authors' cohort, of whom 27% reported more than 150 minutes/week of moderate intensity physical activity, and 31% reported less than 30 minutes/week. Nevertheless, no studies using objective measures have been reported.

While the limited evidence suggests that physical activity levels are low among women with GDM (Symons Downs and Ulbrecht, 2006; Galliano et al, 2019), in contrast, there is growing high-quality evidence of the benefits of physical activity. Specifically; meta-analyses have shown that physical activity interventions can improve glycaemic control (Cremona et al, 2018; Hillyard et al, 2018). A recent systematic review of 12 trials including both aerobic and resistance exercise found that the requirements of insulin therapy, dosage, and latency to administration were improved in the exercise groups (Cremona et al, 2018). This is supported by high-quality evidence that physical activity is a beneficial adjunctive therapy in the management of type 2 diabetes mellitus through its ability to increase glucose uptake and improve insulin sensitivity (Boulé et al, 2001).

There is currently insufficient high-quality evidence to determine the effect of exercise on longer term maternal and infant outcomes (Brown et al, 2017). Aerobic or resistance exercise programmes appear to be effective at improving postprandial glycaemic control and lowered fasting blood glucose. The characteristic exercise programmes are those that are performed at a moderate intensity and for a minimum of three times a week (Harrison et al, 2016). Greater supervision, either face-to-face or via phone follow up, appear to be associated with higher levels of adherence to exercise interventions (Harrison et al, 2016). The challenge remains to translate these established research findings into practical everyday use in a healthcare system where physical activity interventions in secondary care are notably underutilised (Tucker and Carr, 2016).

This evaluation highlights the promising opportunity for motivational interviewing to increase physical activity levels. The diagnosis of GDM can have a profound effect on women and appears to be a moment of change that encourages them to reprioritise their health and lifestyle (Harrison et al, 2019). Positive use of this emotive response is important because of the short window of opportunity for maximising blood glucose control and minimising risk to the fetus.

While motivational interviewing has been shown to increase physical activity in individuals with long-term health conditions (O'Halloran et al, 2014), there is an absence of specific evidence regarding physical activity motivational interviewing interventions in women with GDM. There are successful examples of motivational interviewing being used in other lifestyle interventions among pregnant women. A small pilot study demonstrated significant reduction in alcohol consumption at 2-month follow up after a 1-hour motivational interview (Handmaker et al, 1999). It has also been shown to be effective in improving healthy eating behaviours in pregnant women with type 2 diabetes mellitus (Ásbjörnsdóttir et al, 2019). The multi-centre randomised controlled DALI trial used motivational interviewing principles in women at risk for GDM to address healthy eating and physical activity behaviour changes (van Poppel et al, 2019). They reported increased self-efficacy for physical activity.

The intervention in this evaluation encompasses some of the key elements highlighted in the literature and may explain its effectiveness at increasing physical activity levels by addressing key barriers and enablers. Harrison et al (2019) highlights that women with GDM require clear, simple, specific physical activity messages directly related to pregnancy outcomes that are delivered by a credible source with flexible options tailored to fit in with their lifestyles. The importance of the clinician's role in increasing women's self confidence in their ability to be physically active, as well as provide guidance to overcome barriers to physical activity, has been emphasised (Garland et al, 2019). A systematic review of 14 studies of behaviour change interventions in pregnancy found that a range of BCTs can be implemented to reduce the decline of physical activity during pregnancy. Face-to-face interventions with goal setting and feedback are more likely to be associated with positive change (Currie et al, 2013) and combined face-to-face and telephone interventions have been shown to be effective (Soderlund, 2018).

This service evaluation is a successful example of how a motivational interviewing physical activity intervention can be incorporated into routine care, and women with GDM appear willing to engage. While the findings are positive, they must be interpreted with caution. The sample size was small, non-randomised and lacked a control group. Participation was not mandatory, which may have resulted in a selection bias towards those more likely to respond to motivational interviewing. There were several incomplete datasets as a result of participants not answering the follow-up telephone call. This is likely to be explained by people being unwilling to answer calls from an unknown number (caller identification is withheld from the hospital phoneline).

Limitations

A validated self-reported outcome measure was used; however, this relied on patient recall and has not been specifically validated for pregnant women. No objective measurement of physical activity was taken. Self-reported measures for physical activity are shown to overestimate activity when compared to objective measurement. This may have affected the follow-up result. The fidelity of the motivational interviewing session was not tested and the duration of follow up was limited to 2 weeks.

Recommendations

Further work is required to evaluate this intervention in a randomised controlled trial with objective measurement of physical activity. Longer term follow-up data, including postpartum data, would be valuable to understand whether this intervention can influence longer term outcomes, such as the development of type 2 diabetes. Understanding other clinical outcomes such as blood glucose control, insulin use, maternal and fetal outcomes is required. Finally, the cost effectiveness of this intervention needs to be evaluated to help consider the scalability of this intervention and measure to reduce the number of women lost to follow up.

Conclusions

This quality improvement project provides promising evidence that the approach of integrating physical activity-focused motivational interviewing into routine care for women with GDM is feasible, acceptable and, at least in the short term, can increase self-reported physical activity levels.