Compassion Focused Therapy (CFT) and Compassionate Mind Training (CMT) aim to help people cultivate compassion for self and others. CFT was created to help people respond to self-criticism and shame with compassion and self-supportive inner voices (Gilbert, 2005; 2009; 2010; 2014). CFT is a psychotherapy used in therapeutic settings (Kirby, 2016), and CMT is a programme of contemplative and body-based practices that can be used in non-clinical populations to help people cultivate compassion (Gilbert, 2005; 2009; 2014).

Over the past 10 years, there has been an expanding body of evidence to support the use of CMT to alleviate mental health difficulties and promote wellbeing (Beaumont and Hollins Martin, 2015; Leaviss and Uttley, 2015; Karatzias et al, 2019). In response, CMT is now being implemented in hospitals, prisons, schools, universities and businesses, which makes it appropriate for midwives to now consider its use.

When people use the word compassion, they usually apply it to describe an act of kindness. Yet, at the core of compassion is bravery, with kind people not always having the courage to behave in compassionate ways. Gilbert (2009) describes compassion as a sensitivity to suffering in self and others and having the commitment to alleviate it, with his definition capturing two processes. First, it involves having the courage to engage with one's own or other people's distress, as opposed to avoiding it. Second, it involves being prepared to acquire wisdom to behave appropriately when suffering occurs. It is important to be aware that humans are biological beings, who have a legacy of inherited genes, which are pushed and pulled by motives and emotions that have been socially shaped. With this in mind, CMT can be taught to cultivate midwives' compassion and help them cope with traumatic clinical incidents. In this context, CMT has the ability to reduce self-criticising thoughts and equip midwives to care for themselves in the same way they deliver care to women, family and friends.

Using compassionate mind training in modern midwifery supervision

It could be useful to include CMT within modern midwifery supervision models, with CMT used by the Professional Midwifery Advocate as part of the Advocating for Education and QUality ImProvement (AEQUIP) model (NHS England, 2017), or the new Scottish Clinical Supervision Model for Midwives (Key et al, 2017). Both of these supervision models have restorative elements, which include examining experiences that have affected the midwife emotionally, with emphasis placed upon reducing stress and burnout, which stem from emotional fatigue (Klimecki and Singer, 2012). The restorative component is designed to develop midwives' reflective skills and help them to better manage demanding clinical work (Sheen et al, 2014). The aim is to build resilience through reflecting upon the event, examining how the midwife responded and why, and help restore emotions to a more comfortable place and build resilience to cope in similar future events.

Who should deliver compassionate mind training?

Compassionate mind training should be delivered by someone who has been trained, which could be the midwife's supervisor, manager, midwifery lecturer, Midwifery Advocate, or an independent practitioner. Each Health Board can develop its own system of delivery, with the essential component being that the person chosen has been appropriately trained. This person should be a qualified CMT practitioner, with many courses available on the internet, such as the Compassionate Mind Foundation.

Analysing a scenario to contexualise use of compassionate mind training

In relation to the scenario in Box 1, seven steps have been outlined that can be followed to help equip a midwife with skills to cope with trauma events in the clinical area (Table 1).

Box 1.An example of a traumatic clinical incidentA newly qualified midwife (Willow) was caring for a couple having their first baby (Helena and Findlay). After 6 hours of labour, Helena progressed to second stage. After 10 minutes of pushing, the fetal heart descended into a continuous bradycardia. Willow prepared for a forceps delivery and 12 minutes later a baby girl was born with an Apgar of 1. An attempt to resuscitate was made, and after 25 minutes the baby was pronounced dead. The next day, Willow phoned the birthing unit stating that she would be absent from her shift as she felt unwell, and 1 week later she still had not returned to work. Willow was experiencing repeated thoughts of self blame and anxiety, which were causing her to think about a career change. To reflect upon this event, Willow's supervisor, a delivery suite midwife, and a member of the ‘perinatal bereavement team’ have arranged to meet with her. In accordance with the Code of Conduct (NMC, 2018), pseudonyms have been used.

Table 1. Actions designed to help midwives cope with trauma events in the clinical area

| Step 1 | Organise a meeting to analyse the midwife's experience |

| Step 2 | Build resilience through self reflection and teaching the purpose of developing compassion for self |

| Step 3 | Teach the underpinning theory of compassionate mind training |

| Step 4 | Teach compassionate mind training approaches that develop compassion |

| Step 5 | Write a pre, during and after plan to facilitate return to work |

| Step 6 | Measure effectiveness of the training plan before and after using psychometric scales |

Step 1: organise a meeting

After experiencing a traumatic clinical event, the thought of returning to work fills the midwife (Willow) with anxiety, and so the team organise a meeting for the midwife to meet with a suitable associate (eg supervisor, manager, member of the perinatal bereavement team, lecturer), to reflect upon the traumatic incident.

Davis and Coldridge (2015) describe low mood, fear, distress, guilt, and withdrawal of some midwives who have experienced a traumatic incident in the clinical area. Akin to Willow, these midwives questioned their competence and described worry about whether they could have prevented the tragic outcome (Davies and Coldridge, 2015). Such responses are not unusual, with 15% of Swedish obstetricians and midwives reporting trauma symptoms from being placed in similar situations (Wahlberg et al, 2016). As such, clearly there is a need to build midwives' resilience, with the UK Nursing and Midwifery Council (NMC, 2019) advocating that mental health coping strategies be embedded into midwifery curriculum. In this context, building resilience involves the midwife developing coping strategies, along with teaching them how to respond positively and consistently in the face of adversity (Seery et al, 2010).

Step 2: build resilience

Teach the midwife (Willow) how to self reflect and the purpose of developing compassion for self and others.

Self Reflection

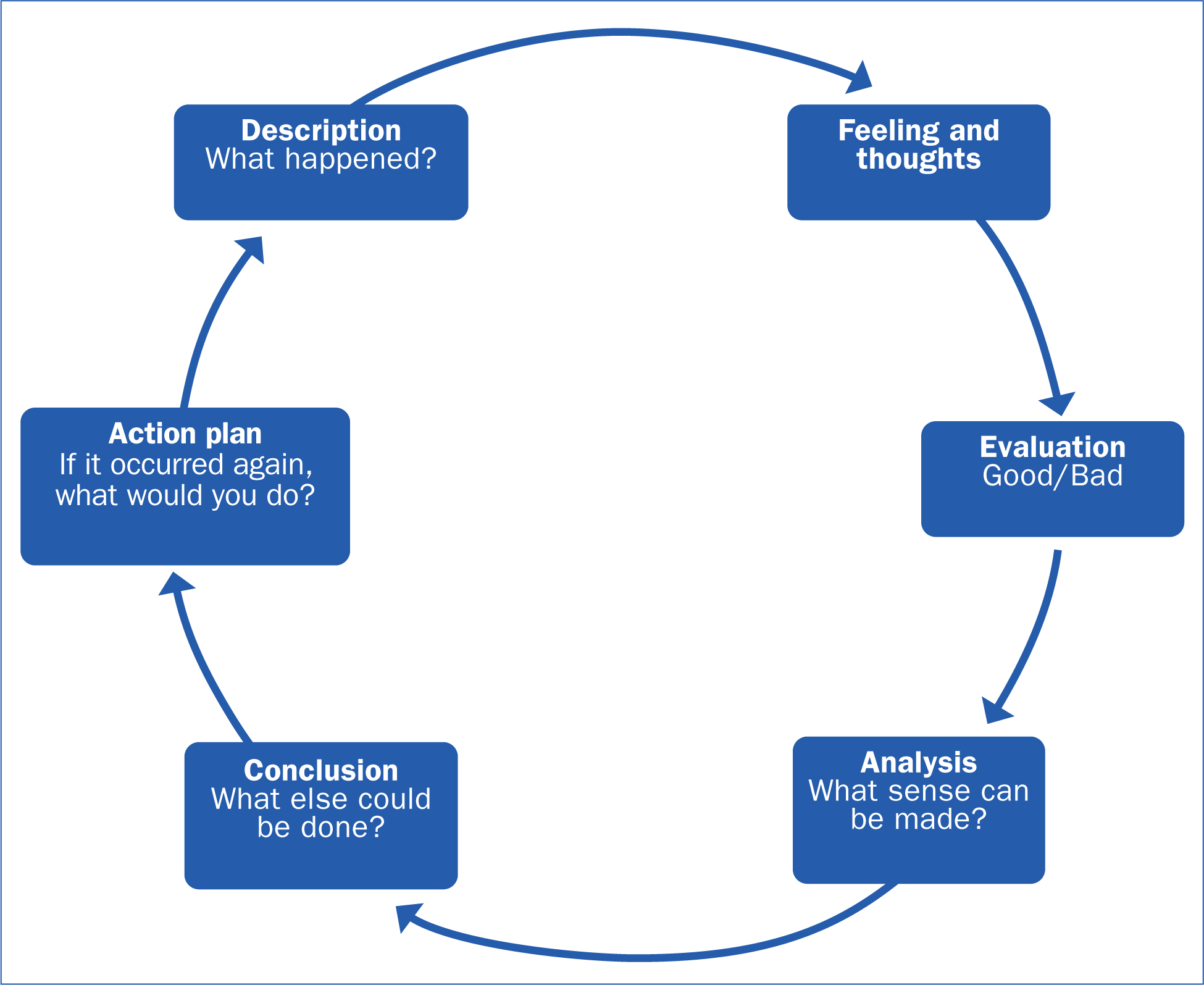

One method of building resilience involves developing self-reflection skills (Grafton et al, 2010). Within the clinical incident described in Box 1, Willow's supervisor organises a meeting to help her recover from the trauma incident and build her confidence to return to work. The first step involved organising a meeting with Willow to reflect upon the trauma incident using the Gibbs (1988) reflective model (see Figure 1).

Figure 1. Reflective model

Figure 1. Reflective model

Responding to suffering with compassion provides a restorative element (Beaumont and Hollins Martin, 2016; Key et al, 2019), whilst analysing the trauma incident using a reflective model will help the midwife (Willow) cope with similar future traumatic incidents (Sheen et al, 2014). During the process, the supervision provided should involve a restorative and compassionate element (Key et al, 2019; Raab, 2014), with focus placed upon building resilience, cultivating compassion for one's own suffering and reducing trauma symptoms, stress, and potential burnout (Klimek and Singer, 2012). Hence, it is important to carry out supervision in a safe protected space (Bishop, 2007).

There are three elements to building resilience: reflecting, responding, and restoring (Key et al, 2019). This means reflecting upon the traumatic incident (Figure 1), analysing how the midwife responded and why, and using compassion to restore emotions to a more comfortable place. To this effect, supervision involves examining what went right and wrong and what potential improvements to practice could be made (Key et al, 2019). As such, the midwife is not just reflecting upon the traumatic incident, but also taking a conscious look at their emotions and behavioural responses to increase understandings of self (Paterson and Chapman, 2013). It is important that the midwife (Willow) is taught to understand that all humans have a tendency towards repetitive self-limiting behaviours (Turetsky et al, 2011), with challenge to negative cycles of thinking and behaviour key (Helsing et al, 2008). An important part of reflection is to address any gaps between actual and good practice and provide affirmations for successful elements to build self-efficacy, self-esteem and confidence. At the end of each meeting, it is important to evaluate the midwife's views about what went well or otherwise.

Develop compassion for self

Compassion fatigue can be reduced by implementing strategies that activate neural pathways associated with compassion, empathic concern, positive feelings, and altruistic behaviour (Klimecki and Singer, 2012; Kim et al, 2020). Compassion ‘aims to nurture, look after, teach, guide, mentor, soothe, protect, and offer feelings of acceptance and belonging’ (Gilbert, 2005). Compassion is at the very heart of CMT, which in the incident described is used to help the midwife (Willow) reduce threat-based emotions and self-criticism. As part of the process, there is a focus upon teaching the midwife to recognise cognitive biases and biological processes that are directed by genes and the environment (Gilbert, 2014).

Step 3: teach the underpinning theory

Teach the midwife (Willow) the underpinning theory of CMT to help her generate a kind and self-supportive inner voice.

CMT, or CFT depending upon context, was developed by Gilbert (2009) in response to his observation that people high in shame and self-criticism often experience difficulty generating kind and self-supportive inner voices. The central therapeutic technique of CFT is CMT, which involves teaching the skills and attributes of compassion. CFT is used when the focus is upon a patient with a diagnosed psychological pathology (such as depression), whilst in contrast, CMT is used in non-clinical populations to help people explore problematic patterns of cognition and emotions relating to anxiety, anger, shame, and self-criticism (Gilbert, 2009).

To date, CFT has shown itself to be effective at reducing trauma symptoms (Beaumont and Hollins Martin, 2015; Leaviss and Uttley, 2015; Karatzias et al, 2019), with a meta-analysis reporting large effect sizes for relationships between compassion and depression and anxiety and stress (Macbeth and Gumley, 2012). Surveys have also shown that self-compassion positively correlates with improved wellbeing (Neff et al, 2007; Van Dam et al, 2011), and reduced psychiatric symptoms, interpersonal problems, and personality pathology (Schanche et al, 2011). This evidence supports that developing interventions that cultivate compassion should work towards improving midwives' ability to cope with trauma, by reducing self-criticism and self-attack (Beaumont, 2016).

What the literature says about compassionate mind training in midwifery practice

To date, only two papers have directly focused upon CMT in midwifery practice (Beaumont et al, 2016a; b). Beaumont et al (2016a) used validated scales to measure student midwives' compassion for others, compassion for self, quality of life, mental wellbeing, and their association with compassion fatigue and burnout. Participants reporting high on self-judgement subscales, scored lower on compassion for self, compassion for others, and wellbeing, and scored higher on burnout and compassion fatigue. The main conclusion drawn by Beaumont et al (2016a) is that midwives could benefit from learning to be ‘kinder to self’, which in turn could help them cope with the emotional demands of clinical practice. In response to these findings, Beaumont et al (2016b) developed a CMT education model informed by evidence that shows that CMT is beneficial in populations who have experienced trauma, through reducing self-criticism and heightening compassion for self and others (Ferrari et al, 2019). This work is ongoing and has the potential to profoundly impact upon midwives' absence and attrition rates from midwifery practice.

To understand how compassion can be used to improve wellbeing, it is first important to understand the psychological model of threat, drive and soothing that underpin the CMT model.

Systems that underpin compassionate mind training

Humans have three genetically programmed internal psychological systems (Gilbert, 2009). The threat system, the drive system and the soothing system.

The threat system directs attention to perceived danger and, when activated, the person responds with anger, anxiety and negative thinking-feeling loops. Also, individuals high on self-criticism and shame have been shown to have dominant threat systems (Gilbert, 2009; Beaumont and Hollins Martin, 2016). In response to the incident portrayed in Box 1, Willow is filled with doubt, shame and self-blame.

The drive system motivates a person to pay attention to helpful resources that relate to doing, wanting, achieving, status-seeking, competitiveness, and avoiding rejection (Depue and Morrone-Strupinsky, 2005). When the drive system is activated, the experiencer responds with joy emotions, which then proceed to reinforce associated successful behaviors.

The soothing system stimulates physiological responses that promote calming, soothing, attachment, and interpersonal connection (Depue and Morrone-Strupinsky, 2005; Gilbert, 2014). Hence, cultivating a compassion-filled internal and external environment should increase the midwife's (Willow's) feelings of safeness and social connection, at the same time as reducing symptoms activated by the threat system (Gilbert, 2014).

These systems thus serve vital roles in keeping people safe and experiencing the ‘good things’ in life. For example, satisfaction of a job well done, and maintaining health and wellbeing. However, the threat system operates on a ‘better safe than sorry’ principle to fulfil its objective (Gilbert, 2009). This can lead to ‘fight, flight or freeze’ responses to perceived rather than actual threats, such as hearing a strange rustling sound walking home late at night, feeling frightened, and then realising it was just litter moving in the wind. When ambitions related to the drive system are thwarted, for instance when something goes wrong in a professional context, the threat system can then be triggered, leading to self-criticism, even if the person themselves is not to blame for the incident. The soothing system, meanwhile, is essential for our psychological, physiological and interpersonal wellbeing (Gilbert, 2009).

What is compassionate mind training?

The aim of CMT is to balance the threat, drive and soothing systems, through developing compassion for self and others and reducing self-criticism. In CMT, compassion is viewed as comprising of a threeway flow (Gilbert, 2014) between:

- Compassion for others (compassion flowing out)

- Compassion from others (compassion flowing in)

- Self-compassion (self-to-self compassion).

Part of developing compassion involves the individual being sensitive to their own distress and engaging with it in a non-judgemental way, and teaching the midwife (Willow) how to activate her own soothing system. For example:

- Breathing exercises to slow the body down

- Imagery, attention, mindfulness and memory training (to calm and soothe the mind)

- Method acting techniques (to practice compassion)

- Recalling events of giving and receiving compassion

- Skills of engaging compassionately with emotions, thinking, and behaviours

- Compassionate letter writing (to lesson shame, self-criticism and fear)

- How to deal with blocks to compassion flow

- To view an outline of a CMT teaching program (Beaumont and Hollins Martin, 2016).

In relation to the incident described in Box 1, the goal is to:

- Develop the person's awareness of own suffering

- Turn towards the person's suffering

- Learn to engage with, not avoid, the person's suffering

- Help the person cultivate self-compassion towards own suffering

- Know how to manage the person's suffering.

An outline of skills and attributes involved in providing compassion can be seen in Table 2.

Table 2. Outline of skills and attributes involved in providing compassion

| Care for wellbeing: develop a caring motivation and desire to relieve and turn towards suffering | Attention: focus the mind on what is helpful and not harmful. Pay attention in the here and now |

| Sensitivity to distress: recognise and be attentive to both own and others' distress | Imagery: use imagery exercises to calm and stimulate the soothing system |

| Sympathy: ability to be emotionally moved by feelings of distress, as opposed to disconnected from them | Sensory: utilise breathing exercises, vocal tones, facial expressions, and body postures to help regulate distress |

| Distress tolerance: tolerate difficult emotions by moving towards them, as opposed to avoiding suffering | Reasoning: learn to reason in ways that are helpful, compassionate, and caring |

| Empathy: tune in emotionally to another's suffering | Feeling: learn to respond compassionately to emotions |

| Non-judgement: step away from judgement, self-criticism, and disapproval | Behaviour: behave in helpful ways towards self and others (requires courage) |

Adapted from Gilbert, 2014

Step 4: teach approaches that develop compassion

Teach the midwife (Willow) CMT approaches that will help her develop compassion for self and others, which can be used to help cope with future trauma events.

In the incident in Box 1, Willow is questioning herself, experiencing anxiety, being self-critical and worrying about returning to work. In this context, compassion-based interventions are used to help midwives (like Willow) develop self-efficacy, self-esteem, and confidence to return to work.

(i) Divert attention using a sound-based mindfulness exercise

Divert attention to focus on breath, sound and body (Irons and Beaumont, 2017). The example in Box 2 illustrates how sound can be used to anchor a person's attention.

Box 2.Sound-based mindfulness exercise (adapted from Irons and Beaumont, 2017)

- Find a quiet and relaxing place to sit

- Sitting comfortably in an upright position in a chair, focus on your body and just breathing in and out (around 30 seconds)

- After the initial 30 seconds, widen your attention away from your body and pay attention to the sounds that can be heard around you. Be receptive to each sound as it arises and disappears. You are ‘in the now’, simply attending to each sound as it happens (around 60 seconds)

- Select just one sound and be aware of the direction it arises from, its nature, character, volume, pitch, tone, and whether it is continuous or intermittent (around 60 seconds). Attempt to anchor your attention in this sound and describe its characteristics. When your mind wanders, keep drawing it back to this sound. Also, when distracted by thoughts, worries or concerns, attempt to bring your attention back to noticing the sounds around you again (around 60 seconds)

- Repeat activities 2 and 3

- Now widen your awareness to what is happening in the room around you and bring yourself into the ‘present moment’

- Reflect upon how it felt to use sound to anchor your mind and attention

(ii) Teach soothing rhythm breathing

Breathing exercises can trigger alternative feelings, behaviours, and thought patterns. Hence, activating the parasympathetic nervous system using soothing rhythm breathing is used to regulate heart rate, soothe the mind, and calm the body (Box 3).

Box 3.Learning to use soothing rhythm breathing (adapted from Irons and Beaumont, 2017)

- Find a quiet and relaxing place to sit

- Sitting comfortably in an upright position in a chair, focus on your body and just breathing in and out (around 30 seconds)

- Notice the sensations present as you breathe in and out. If your attention becomes distracted, gently attempt to bring it back to your breathing without judging or criticising yourself

- Paying attention to the flow of your breath, attempt to induce a calming soothing rhythm to your breathing. Soothing rhythm breathing involves breathing, slower and deeper than usual, yet in a smooth, even and comfortable way. When you are distracted by thoughts, emotions, or external stimuli, gently draw your attention back to the calming quality of your breathing. It can be helpful to count your breaths from 1 to 5 as you do so (see below)

- Continue this style of breathing for another 3–4 minutes, maintaining your attention on your breath. At around 5 minutes, widen your awareness to the whole room by listening for the sounds around you. Bring yourself into the present moment

- Reflect upon your experience of engaging with soothing rhythm breathing. What did you notice about your thoughts, physical sensations, and feelings?

- In-breath 1–2–3–4–5 seconds

- Hold 1 second

- Out-breath 1–2–3–4–5 seconds

- Hold 1 second

- In-breath 1–2–3–4–5 seconds

- Hold 1 second

- Out-breath 1–2–3–4–5 seconds

- Hold 1 second

(iii) Use imagery to create a safe place

The person can be guided through an imagery exercise that cultivates the soothing system and ‘creates a safe place’ (Box 4).

Box 4.Creating a safe place

- Find a quiet and relaxing place to sit

- Sitting comfortably in an upright position in a chair, focus upon your soothing rhythm breathing

- Conjure up an image of a place you consider to be sheltered and soothing (this safe place may be familiar or created)

- Mindfully pay attention to what you see in this image, such as colours, shapes, and objects (around 30 seconds)

- Notice sounds present, observing different qualities and how you are feeling (around 30 seconds)

- Notice any soothing or comforting smells that are present (around 30 seconds)

- Notice any physical sensations, such as touch, warmth of the sun, feel of the grass or sand beneath your feet (around 30 seconds)

- Is someone or an animal present with you (around 30 seconds)?

- Imagine that your safe place has an awareness of you. That it is welcoming you in, happy to see you, and wanting you to feel safe and calm (around 60 seconds)

- Consider what you would like to do whilst in this safe place (such as being still and content and ‘being in the moment’). Alternatively, you are free to explore this place (walking, swimming, or playing a game)

- When you are ready, widen your awareness to the full room around you. Notice sounds and bring yourself into the ‘present moment’

- Reflect upon what it was like to visit this soothing place?

(adapted from Irons and Beaumont, 2017)

(iv) Explore obstructive thinking

Worry about returning to work and what peers are thinking has filled the midwife's (Willow's) mind with doubt, shame, and self-criticism. In attempts to diminish these negative thoughts, empathetic statements can be used to cultivate compassionate attention, thinking, and behavior:

- Other midwives have experienced similar situations, and like you have found them hard to handle

- It is completely understandable that you feel the way you do. This incident is upsetting, and it difficult to witness another suffering

- Remember that your thoughts are not actual facts, and others may not view events as you do

- Speaking to others about your feelings can help you come to terms with this traumatising experience

- The way you feel today will pass

- We can teach you strategies to deal with this experience, which will help you cope in the future

(v) Label upsetting emotions

Identifying and labelling of emotions can be used to develop emotional intelligence. In this respect, emotional intelligence is a person's ability to recognise emotions of self and others, and being able to discriminate between different feelings and label them appropriately. Emotional interpretation guides a person's thinking and response behaviours in a given situation. Some useful prompts can be used to explore and label the midwife's emotions.

- Your threat system has been activated, which makes you predisposed to having ‘biased’ and ‘all or nothing thoughts’ (discuss) such as good/bad, right/wrong. The situation is not black or white

- When people experience intense emotions their heart rate rises, their voice reverberates, and they can often feel unwell or faint (discuss)

- Attempt to label your emotions (ie the 27 emotions captured by Keltner and Cowen (2017) include admiration, adoration, aesthetic appreciation, amusement, anger, anxiety, awe, awkwardness, boredom, calmness, confusion, craving, disgust, empathetic pain, entrancement, excitement, fear, horror, interest, joy, nostalgia, relief, romance, sadness, satisfaction, sexual desire, surprise)

- Discuss thoughts associated with labelled emotions (such as ‘I cannot cope’, ‘What do others think of me’, ‘I cannot do this job’)

- What are your response behaviours? (such as wanting to hide away, avoid future incidents, or abandon the midwifery profession).

(vi) Carry out compassion for others exercises

Ask the midwife (Willow) to imagine listening to another who has experienced a similar traumatic incident. For example:

- What would you say to a friend who has experienced a similar incident and feels the same way you do? Now reverse this procedure and talk to yourself in this compassionate way.

- Write a compassionate letter to another midwife who is suffering after experiencing a traumatic incident? Now reverse this procedure and write a compassionate letter to yourself

- Look into a mirror and practice talking to another midwife about their traumatic incident. When you are doing this, use a compassionate tone of voice, positive body language, and affirmative facial expressions. Now reverse this procedure and offer yourself the same compassionate conversation.

Step 5: write a pre, during and after plan

Write a pre, during and after (PDA) plan with the midwife (Willow) to help build self-esteem, self-efficacy and confidence to return to work.

As sports coaches encourage professional competitors to do, write a PDA plan with the midwife (Willow). For example, a footballer prepares for a match by rehearsing penalties and imagining scoring the winning goal. They also plan to eat particular foods, follow an exercise schedule, design a warm-up, and conduct psychological activities to ‘fire them up’ before a game, such as visualising their team being awarded the gold cup. In a similar fashion, the midwife can be helped to write a pre-plan, which includes time spent on each of the CMT approaches (see Table 3).

Table 3. A compassionate mind training informed pre, during and after plan

| Traumatic incident | Pre-plan | During plan | After-plan |

|---|---|---|---|

| Date of meeting: | Date of meeting: | Date of meeting: | Date of meeting: |

Source: Irons and Beaumont, 2017

In preparation for first day back at work, the during-plan can include supportive statements that the midwife can practice and repeat when fear related thoughts emerge. For example:

- Other midwives have progressed and grown after experiencing what I have

- It is all part of a midwives' job

- The way I feel now will pass. Today and ongoing, I am going to enjoy my work

- Fears are just thoughts in my head. I can cope, as I have coped many times before

Also, the midwife (Willow) can carry an object in her pocket (such as a stone or meaningful piece of jewelry), which reminds them that thoughts are not facts and to be compassionate and kind to self.

In the after-plan, the midwife (Willow) can write a reflective compassionate letter to herself, which includes praise for facing anxieties. To view a profile where the midwife can record their PDA-plan, see Table 3 (Irons and Beaumont, 2017).

Strengths and limitations of compassionate mind training

One strength of the CMT model includes development of an enhanced understanding of human distress, both physically and psychologically, which has evolved over millions of years. A second benefit involves enhancing the receiver's understanding of their internal drive for social fairness, status, and pursuit of wealth. Together, these strengths diminish the idea that the person is responsible for their thoughts and feelings, which includes blame. One limitation of the CMT model involves an optimistic belief that a person can learn how to be more compassionate, which involves rewiring the brain to become kinder, more content, peaceful, and accepting. Some people have greater aptitude to develop compassion, which is influenced by the quality of care they receive in their own social environment and brain plasticity, with younger brains more able to make new connections. A further limitation occurs when the midwife continues to exist in a threatening environment. Despite these limitations, providing CMT provides helpful ways of understanding threatening situations and can reduce self-blame when upsetting events occur.

Argument for adding compasstionate mind training to the restorative supervision model

Restorative supervision contains elements of psychological support, which include listening, supporting, and challenging the midwife to improve their capacity to cope, especially when difficult and stressful situations prevail (Proctor, 1988). CMT makes a further useful addition to the supervision model for the following reasons:

- Gilbert (2010) argues that cultivating self-compassion can be the antidote to self-criticism. CMT may help midwives who experience self-critical judgement and self-doubt cultivate compassion for their own suffering

- When self-criticism, anxiety, low-mood and/or self-doubt are holding the midwife back or are leading to unhelpful behaviour patterns, CMT will help to counter these well-rehearsed patterns

- CMT will help the midwife develop self-awareness of their self-criticism and self-doubt and learn methods of acknowledging these thoughts

- The CMT practitioner can teach the midwife to understand human evolution, biology, and attachment theory, to help them make sense of why they worry, self-critique and experience stress, anxiety, and depression

- The CMT practitioner can teach the midwife to understand the key emotion regulation systems and how CMT practices can be used to soothe and regulate an ‘overactive’ threat or drive system.

In addition to restorative supervision, practising CMT techniques will help the midwife develop more compassionate responses towards themself. Through activities that are specifically developed to activate the soothing emotion regulation associated with care and connection (such as mindfulness, breathing practices, and guided imagery) the midwife will learn self-care strategies that can be used ongoing throughout their life.

Step 6: measure effectiveness of the plan before and after using psychometric scales

Use psychometric scales to measure before and after improvements in the midwife's (Willow's) levels of traumatisation, compassion engagement, compassion for self, self-criticising and attack, professional quality of life, and mental wellbeing.

A midwife who has experienced a traumatic clinical incident, may be experiencing PTSD. Hence, it is important to check for symptoms of PTSD or Complex-PTSD (CPTSD) using the International Trauma Questionnaire (ITQ) (Cloitre et al, 2019). The ITQ is a scale that has been validated to diagnose PTSD and CPTSD in accordance with the WHO (2018). If symptoms of PTSD are present, the sufferer should be referred for appropriate diagnosis and treatment.

Other psychometric scales can also be used to measure effectiveness of the supervision meetings and the CMT PDA-plan:

- Compassionate Engagement and Action Scales (Gilbert et al, 2017)

- Self-Compassion Scale (Neff, 2003)

- Self-criticising/Attacking Scale (FSCRS) (22-items) (Gilbert et al., 2004)

- Professional Quality of Life Scale (Stamm, 2009)

- Short Warwick and Edinburgh Mental Well-being Scale (Tennant et al, 2009)

These questionnaires can be issued at 2-3 timepoints:

- Timepoint one: at first meeting

- Timepoint two: post implementation of the CMT PDA-plan (which may be endpoint if scores are good).

- Timepoint three: Continued meetings until mutually agreed endpoint.

To view a summary of the described CMT approaches that develop compassion (Table 4).

Table 4. Compassionate mind training approaches designed to assist staff to cope with traumatic clinical incidents

|

Conclusions

This paper has described an intervention that supervisors, managers and midwifery lecturers can implement to facilitate a midwife to recover from experiencing a distressing incident in clinical practice. A CMT PDA-plan has been outlined that can be implemented to help traumatised midwives build resilience, cope with their emotions and negative thinking, and build courage to face further similar events. In this paper, CMT has been described in a context that will help midwives who are questioning their ability to practice effectively and build their confidence to face future challenge. In this context, CMT activities have been proposed to help midwives cope with adversity, reduce perceptions of threat, and improve professional wellbeing. Embedding CMT into everyday clinical midwifery practice could markedly improve professional wellbeing, reduce abscense rates, and decrease levels of attrition from the profession. In relation to teaching midwives skills that enable them to care for their mental health during their career, it is important to introduce the CMT model early on and ideally during undergraduate degree programs. The author(s) of this paper have begun this work in their own universities.