Induction of labour, whereby the onset of labour is stimulated using either pharmacological or mechanical methods, is one of the most common obstetric procedures carried out in the UK (McCarthy and Kenny, 2014). The incidence of women receiving induction of labour has increased over the past 10 years. In 2008, the Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists (RCOG) calculated that one in five women in the UK had labour induced, while latest figures suggest that the induction of labour rate is approximately 29.4%, and that this is on an upward trend (NHS Digital, 2017). This increasing number of women receiving induction creates its own challenges. Although induction of labour is a safe procedure for the pregnant woman at term, the process is not without risk (Schwarz et al, 2016), and problems include: increased pain and reduced efficiency when compared to spontaneous labour (National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE), 2008); concerns related to the participation in the decision-making process (Henderson and Redshaw, 2013); and a disparity between women's expectations of labour and their lived experience (Shetty et al, 2005; Gatward et al, 2010).

In their study of 936 women, Hildingsson et al (2011) found that induction of labour negatively affected women's experiences of giving birth, with many feeling anxious and fearful about the impact that the procedure would have on them and their baby. In recognition of the challenges that the induction of labour process creates for both the pregnant woman and maternity services, an audit of local service provision was undertaken. The setting was a maternity unit with an estimated 5000 per year. The purpose of the audit was to identify problems with the existing induction service. It was anticipated that following the audit, plans would be devised to tackle concerns and improve the care that the women received.

Auditing the existing induction service

An audit of the induction of labour process was undertaken in the local NHS Trust Maternity Services between May and December 2016. Flottorp et al (2010: iv) define audit as:

‘Any summary of clinical performance of health care over a specified period aimed at providing information to health professionals to allow them to assess and adjust their performance’.

Audit commonly encompasses a quality improvement cycle that gauges care in relation to set standards, and implements action to improve care while monitoring them to ensure that the improvements are in accordance with the agreed standards (Twycross and Shorten, 2014). As such, the use of audit as an evaluation tool was deemed to be appropriate to assess the induction of labour process in the maternity unit. The audit was approved by and conducted in accordance with research and development guidance at the local NHS Trust and wider NHS Internal Audit Standards (Department of Health, 2012).

The audit gathered data that would help to generate a detailed understanding of the induction process, so that the proposed intervention could be targeted and improve the quality of care (Sidani, 2015). The audit collected data through a retrospective analysis of women's notes from May to December 2016 that examined all records of women who had labour induced during this time (n=870). Data were collected on the outcomes of pregnancy following induction of labour, including mode of birth, and the time from admission to birth to examine the issue of delay. These data were analysed using simple descriptive statistics to ascertain how the induction procedures affected the care received. As part of this audit, complaints received by the service and patient feedback mechanisms were also evaluated.

Audit results

The audit identified several issues that would need to be addressed if the service were to improve. These concerns were divided into two groups: the pregnant woman's perspective and service provision issues.

It emerged that the maternity service received a considerable number of complaints from women about the induction process, which were predominately related to the prolonged stay in hospital from time of admission to birth. The audit found that 29% of women who had an induction in the local NHS Trust had experienced a delay of this nature. Furthermore, feedback from women indicated that the induction process generated stress and anxiety, due to limited or ineffective communication, which had given women unrealistic expectations about the procedure.

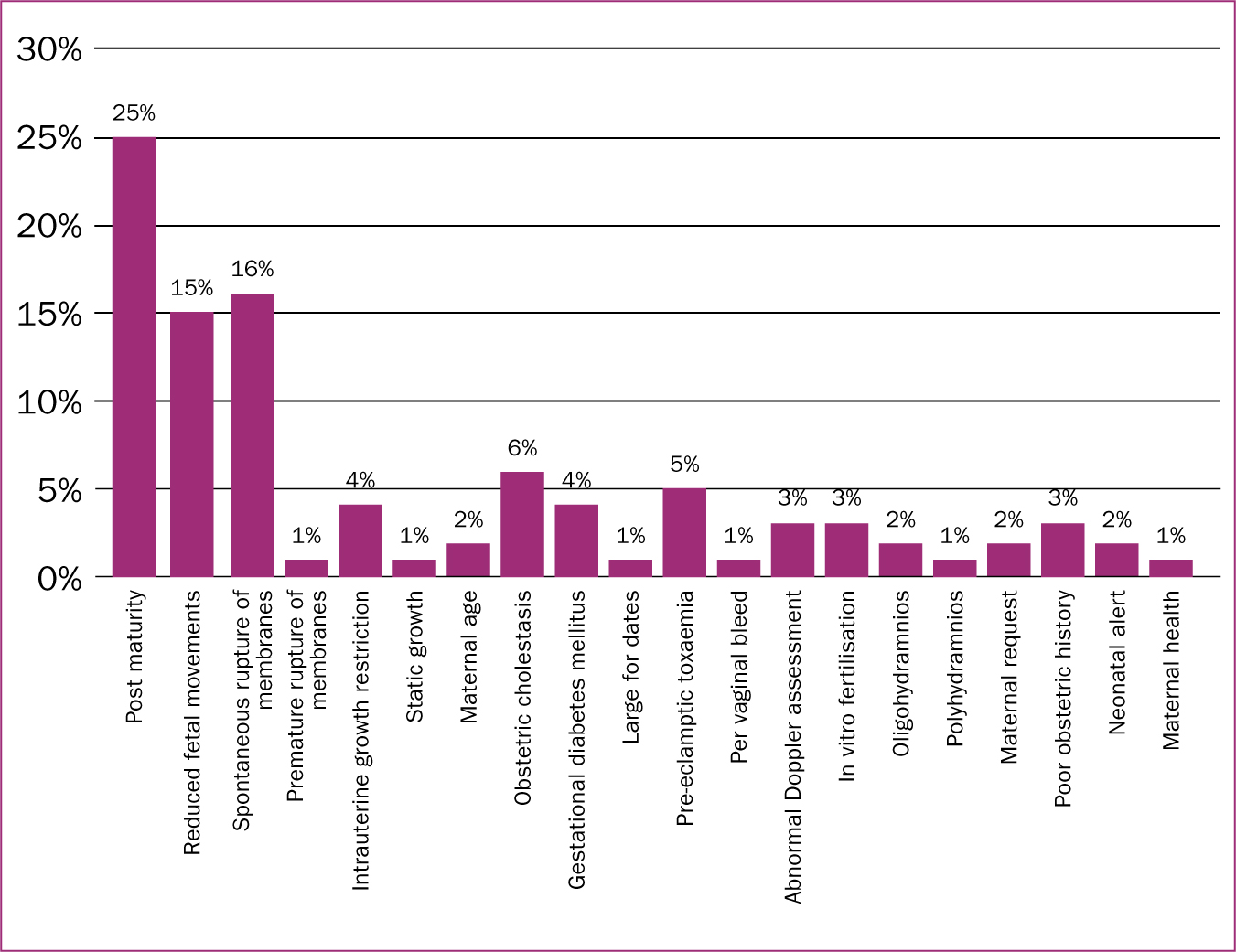

Additionally, the audit identified that the maternity service was experiencing an increase in the number of women who were receiving induction of labour. The audit revealed that the induction rate locally was between 27-32%, which is consistent with the latest statistics for the UK (NHS Digital, 2017). Figure 1 represents the reasons for induction of labour at Medway NHS Foundation Trust.

The audit also found that the guidelines were outdated and did not support the provision of quality care. This created a fragmented system where there was a lack of coordination and communication in terms of who was responsible for the management of women receiving induction, which then affected the number of complaints that the service received. The lack of understanding of staff roles and responsibilities also caused issues in the reporting of incidents related to induction, which hindered the delivery of high quality care.

Implementing change

Once all the audit data had been collected and analysed, several key issues were identified in relation to induction of labour and the care that women experienced. The audit revealed that there was limited management and control of the induction process, particularly when women were admitted to the maternity unit. Different members of the clinical team had access to the booking system, which meant that women were often provided with an admission date, regardless of the workload capacity within the maternity unit. This generated delays and dissatisfaction for women, and comments such as:

‘No one told me that I would not be induced on the date I had been given and that I would have to wait a long time until my labour could be started.’

This remark was echoed by many other women who had labour induced. Discussions took place with senior staff at the maternity unit to consider how these concerns could be addressed.

Team Maia

It was decided that a new team of midwives (Team Maia) would be created to oversee the induction process and liaise with both obstetric and midwifery staff. This new team of midwives was created to drive the new pathway forward and address the problems created by the older procedures. However, to put this new team in place, a business plan had to be agreed. This was in part due to the 1.8 full-time-equivalent midwives who would be required to manage and provide care to women on the new pathway.

NICE (2007) suggests that, for change to be successfully implemented, it is important to recognise that there are several barriers that need to be overcome, which include:

Team Maia were therefore trained on the different methods of induction that would be used as part of the new pathway. This included instruction on the use of the cervical ripening balloon, which has been demonstrated to be an effective method for induction of labour (Jozwiak et al 2012).

Team Maia midwives were responsible for the organisation of all pre-induction clinic appointments. The clinic was established to confirm the wellbeing of the fetus and suitability for induction before the process began. As part of the appointment, the pregnant woman receives an ultrasound scan to monitor fetal biometry and to estimate fetal weight. An amniotic fluid index is also taken, together with a fetal Doppler assessment and a measurement of cervical length, all of which provide valuable information on fetal wellbeing (Tsang and Wyn Jones, 2014). Indeed, cervical length measurement can be used as a predictor for successful induction of labour (Gokturk et al, 2014).

This additional information from local services has created a clearer referral system. The obstetrician who refers the woman for induction is now able to provide Team Maia with a range of dates for certain women when booking, which enables the induction list to be more evenly distributed throughout the week. This is particularly useful for women who have conditions such as symphysis pubis dysfunction. This change to the induction process has also helped to ensure that there is capacity to provide induction of labour for women at 40 weeks and 12 days, or for women who have had in vitro fertilisation to be induced at 40 weeks' gestation. Equally, the assessment of fetal wellbeing has also identified women who might require induction due to poor Doppler assessments. Women who require urgent induction referrals can be accommodated and prioritised, as women can be discharged to await their date for induction if all is well after the assessments of fetal health.

Updated guideline

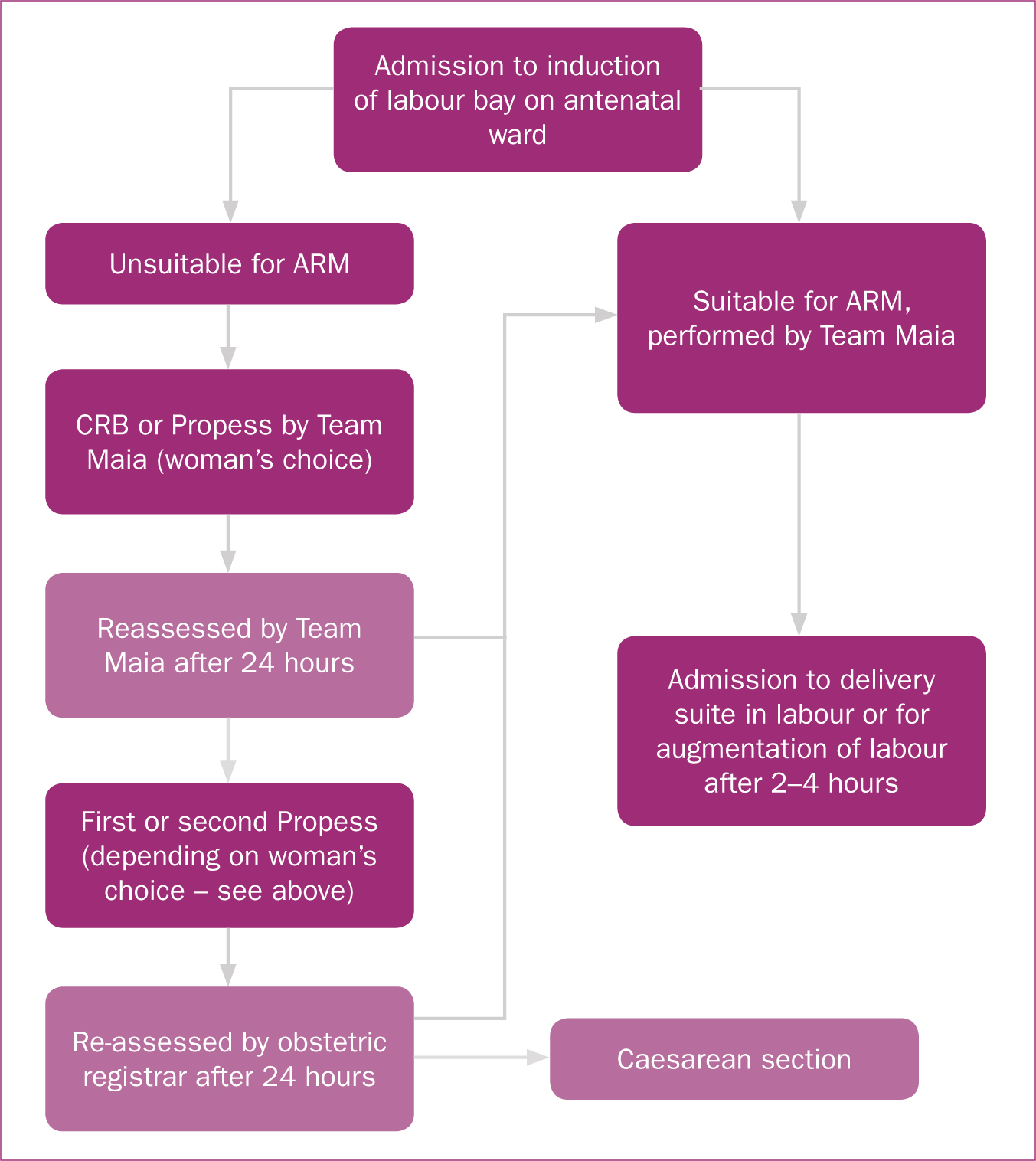

As the guideline that was in use under the old system required updating, a new guideline was created that adhered to NICE recommendations (NICE, 2008; 2015). This guideline was drafted with a panel of experts, including obstetricians and experienced midwives. Up-to-date evidence informed the guideline and local practice (NICE, 2015). The new agreed guideline has been simplified, with an agreed induction of labour pathway (Figure 2) for clinicians to follow.

The guideline was created to minimise the variation in practice and to provide clear guidance on where, when and how women should receive induction of labour, and when it is appropriate for them to be transferred to the labour ward. Clear information is a prerequisite for quality care provision and essential for the enhancement of the patient experience (Freeman and Hughes, 2010). Integral to this process was the requirement for improved communication with the different health professionals who might be involved in providing care to pregnant women, including midwives, obstetricians and sonographers. In addition, education and training was provided for hospital and community midwifery colleagues through mandatory training sessions and visits by Team Maia to the community teams in their work settings. Antenatal education and preparation is beneficial to women's understanding and expectations of the induction process and how it will be managed (Cooper and Warland, 2011; Spiby et al, 2014), and so during these sessions, Team Maia were able to inform midwives about the new induction of labour guideline and the structure of the pathway. Following this training, community midwifery teams were able to cascade this information to women who may require induction and prepare them for the treatment and care they will receive.

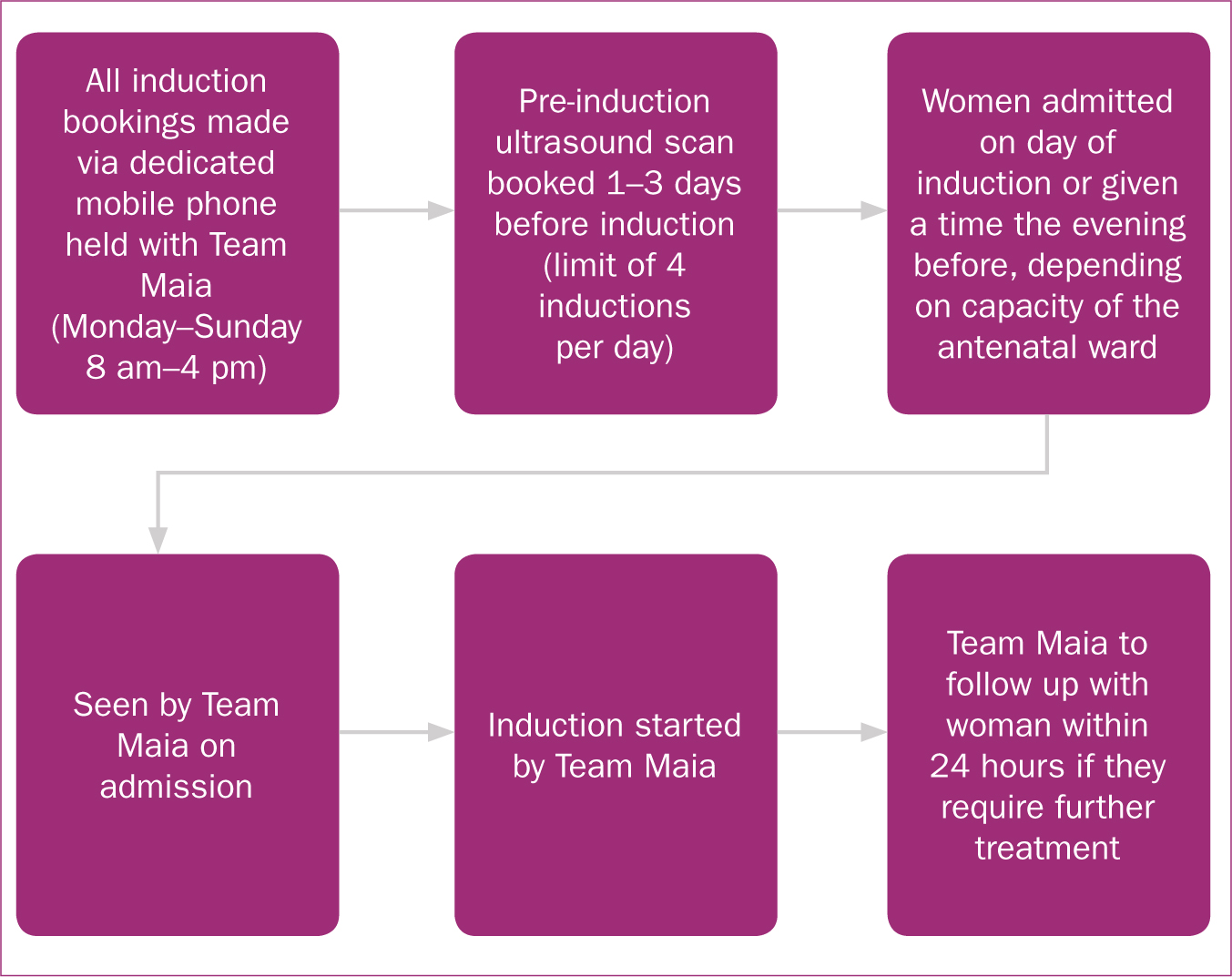

The new induction of labour pathway

The new induction of labour pathway (Figure 3) provides a service whereby Team Maia work 7 days per week between the hours of 8 am and 4 pm. This working pattern is shared between the members of the team. All bookings are taken via a dedicated phone line, which enables the midwifery team to work autonomously, organising the induction diary and ensuring that there is an even daily workload. This process enables the efficient provision of care to pregnant women requiring induction, from initial admission and assessment, through to transfer to the labour ward. Team Maia now arranges transfers to the labour ward, which helps to minimise the delay that pregnant women had previously experienced.

As part of the new process, all induction procedures begin during daytime hours (8 am to 4 pm), with a further review after 24 hours if additional management is required. This change has led to an increase in continuity of carer and greater maternal satisfaction, as Team Maia are available for both the initial examination and for follow-up, which reduces anxiety for women undergoing induction. Furthermore, the partners of women receiving induction are now able to stay overnight if they choose, which provides additional support for the woman and helps to improve emotional wellbeing.

Enhanced information provision for women

The need for clear information to support the pregnant woman's decision-making and to manage her expectations of the induction process is a key part of the provision of quality care (Gatward et al, 2010). To address women's dissatisfaction with the information provided about the induction process previously, a new information leaflet was created. The leaflet contained material about the induction of labour pathway, the pre-induction clinic and methods of induction, including artificial rupture of membranes, the cervical ripening balloon and Propess pessary. Importantly, the leaflet also contained information about Team Maia and their contact details. This information was distributed in both hospital and community settings.

Feedback on the new pathway

Following the implementation of the pathway, an audit was undertaken to determine whether it was functioning effectively and addressing the issues identified in the previous audit. An evaluation of these audit data found that the new pathway provided a straightforward route through the induction process for staff to follow, while enabling a manageable workload for the midwives working in Team Maia. The system of having a dedicated phone line administered by Team Maia, a policy of commencing induction during clinical hours (8 am-4 pm) and a limit of four inductions per day has ensured that, of the 463 women booked and seen by Team Maia, 91% have labour induced within this timeframe. While it is not possible to eradicate delays completely, there has been a significant reduction in waiting times and delays for women. The 9% of women who underwent induction outside of these hours have done so due to an urgent referral from the obstetric team or because of capacity issues and workload pressures in the maternity unit.

The audit of the new pathway showed that the delays often occurred in clusters of 3–4 days' duration. Reasons included closure of the obstetric and neonatal units, and periods where there were more women in spontaneous labour or experiencing spontaneous rupture of membranes on the labour ward, which then created delays for women receiving induction. Staff were advised that the aim of the new pathway was to transfer women to labour ward within the same day, if possible, and that any delay to the woman's plan of care should be treated as urgent. Under the new pathway, senior obstetricians and midwives are informed of any deviation in the timeframe for induction, so that plans of care can be formulated to address the delay. If there are no beds on the labour ward, the woman will stay in the induction of labour bay on the antenatal ward and will be updated about transfer times. She will then be transferred to the labour ward once a midwife becomes available there.

The new induction of labour pathway has created a change in staff attitudes towards women receiving induction, who are now prioritised for admission to the labour ward. This has been achieved through clear communication with labour ward staff, and additional education as part of mandatory training sessions. The new pathway has increased communication and collaboration with colleagues who participate in the care of women receiving induction. Downe et al (2010) recommend that in collaborative environments, the potential for care to be enhanced is increased, as the environment will cultivate confident and respectful professional relationships. This has been witnessed in the local induction of labour pathway, which has received positive feedback from health professionals involved in the care of women receiving induction.

One of the main objectives for the new pathway was to reduce the number of complaints related to the length of hospital stay. The dedicated specialist midwives within Team Maia, who are competent and confident about managing the new pathway, have ensured that the number of women who experience a protracted stay on the antenatal ward has been reduced. This improvement has been mirrored in the qualitative feedback the new pathway has received through service user questionnaires that were given to women on the new pathway (n=463). This questionnaire was distributed in accordance with research and development guidance at the local NHS Trust and wider NHS internal audit standards (Department of Health, 2012). Before completing the questionnaire, participants were informed that the feedback would remain confidential and anonymous, and that participation was voluntary. The participants who gave feedback were a diverse sample, and included both primi- and multigravid women, women who had experienced the service for the first time and those who had had induction previously. The questionnaire achieved a response rate of 50% (n=232).

Feedback from women who had used the service for the first time noted that the process was well organised, with the induction being commenced in a timely manner, producing positive outcomes. The women who had previously had labour induced commented that, in their view, the service had improved. Women were also interviewed by Team Maia about their experience of the new leaflets, in order to further enhance the provision of information. Women reported that the material in the leaflet, including the designated phone number to access Team Maia, improved understanding and made them feel supported. This helped to manage their expectations and increased their levels of satisfaction.

Conclusion: moving the service forward

The induction of labour pathway has now been functioning for 1 year. During that time, the service and pathway have evolved as a result of continuing audit evaluation and service demands. To ensure that the pathway continues to provide care that is sustainable and meets the needs of the local population (National Maternity Review, 2016), the induction process is now an integrated part of the antenatal ward provision, which will help to prevent delays, both now and in the future, when the local population is predicted to increase (Kent County Council, 2017). The new induction of labour pathway has been widely disseminated to other NHS Trusts in England through conference presentations and has been implemented by several maternity units nationally. Team Maia has also received an innovation award in recognition of the improvements to the provision of care that pregnant women experience.

The induction pathway itself has been developed and improved so that artificial rupture of membranes is now performed by Team Maia in the induction of labour bay on the antenatal ward, once a midwife and room are available on the labour ward. Once labour is established, Team Maia transfer the woman to the labour ward, where care is provided by labour ward midwives. Once labour has begun, whether in the induction of labour bay or in the labour ward, midwives are able to help women who meet the midwifery-led unit admission criteria to choose whether to be transferred to the unit. This has increased normality for women receiving induction, and the rate of vaginal birth after artificial rupture of membranes has increased to 81%. This is in part responsible for the women's enhanced opinion of the service.

The training programme has continued and has been extended across the maternity service, helping to improve health professionals' attitudes towards the new pathway. Managing change and shifting attitudes within maternity care can be challenging (Nicholas and Qureshi, 2004), and this was seen locally, where there was some resistance to the modification in practice that the new pathway created. Nevertheless, the negative perceptions have slowly transformed as the positive effects of the pathway have become evident. Further education and training have improved understanding of the pathway and the benefits for women receiving induction of labour.