Midwifery care influences women's physical and psychological outcomes after birth (Taheri et al, 2018). Improving the care provided helps promote women's postpartum health and wellbeing (McKelvin et al, 2021).

Multiple studies have assessed midwifery care using life-saving outcomes for women and children, such as mortality and complications, as indicators of the quality of care (World Health Organization (WHO), 2007; WHO et al, 2023). Other indicators include the proportion of women who use maternity facilities and the percentage of births attended by skilled birth attendants (WHO et al, 2018; Vallely et al, 2023). Outcomes for measurements of midwifery care vary widely, and include birth experience (Dencker et al, 2010; Nilvér et al, 2017), birth satisfaction (Hollins Martin and Martin, 2014), women's autonomy (Vedam et al, 2017a), self-determination (Vedam et al, 2017b) and quality of care (Heaman et al, 2014; Truijens et al, 2014; Scheerhagen et al, 2019; Dwekat et al, 2021).

In the last decade, there has been increasing research on the quality of midwifery care globally, in order to ensure positive birth experiences and birth satisfaction. Understanding women's subjective experiences of intrapartum midwifery care is important for improving it. A common understanding between women and midwives of the attributes that make up good intrapartum midwifery care (the overall concept of care) is also important, as the concept can be applied to practical care and midwifery education, as well as being used to develop a model for care. However, no study has clarified the concept, as existing evaluation indicators are diverse (WHO, 2007; Dencker et al, 2010; Heaman et al, 2014; Hollins Martin and Martin, 2014; Truijens et al, 2014; Scheerhagen et al, 2015; Nilvér et al, 2017; Vedam et al, 2017a, b; WHO et al, 2018; 2023; Dwekat et al, 2021; Vallely et al, 2023).

This review aimed to organise and define the concepts of good intrapartum midwifery care from the perspective of women receiving care, in order to improve the quality of midwifery care and promote positive birth outcomes for women.

Methods

Rodgers and Knafl's (2000) method of conceptual analysis holds that concepts are fluid and subject to change according to context, such as the passage of time and social background. This was the philosophical basis of this review's analysis, deemed suitable as intrapartum midwifery care is affected by changes in social background. This study sought to clarify the concept of intrapartum midwifery care from women's perspectives by defining its antecedents, attributes and consequences, using the following definitions (Rodgers and Knafl, 2000):

For vaginal births, the intrapartum period was defined as from the onset of labour (uterine contractions with regular pain within 10 minutes) to 2 hours after birth. For caesarean births, it was defined as the onset of labour from admission to hospital for birth to the period when post-surgery bedrest instructions were lifted.

Search strategy

Literature published in English were searched for using PubMed, the Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature and Web of Science. The search terms used were (((Nursing care) OR (Midwifery)) AND (Parturition)) AND ((Mother*) AND (Experience*))). As the classifications of midwives and nursing midwife qualifications differ between countries, ((Nursing care) OR (Midwifery)) was used as a search term to indicate midwifery care. Literature published in Japanese was searched for using Ichushi-Web. The search terms were (((Midwifery/TH or Midwifery/AL) AND (Care/AL)) AND ((Delivery/TH or Delivery/AL) OR (Birth/TH or Birth/AL)) AND (Mother/TH or Mother/AL)). Manual searches were conducted for literature not available in these databases and added using the reference lists of available studies and Google Scholar.

Eligibility criteria

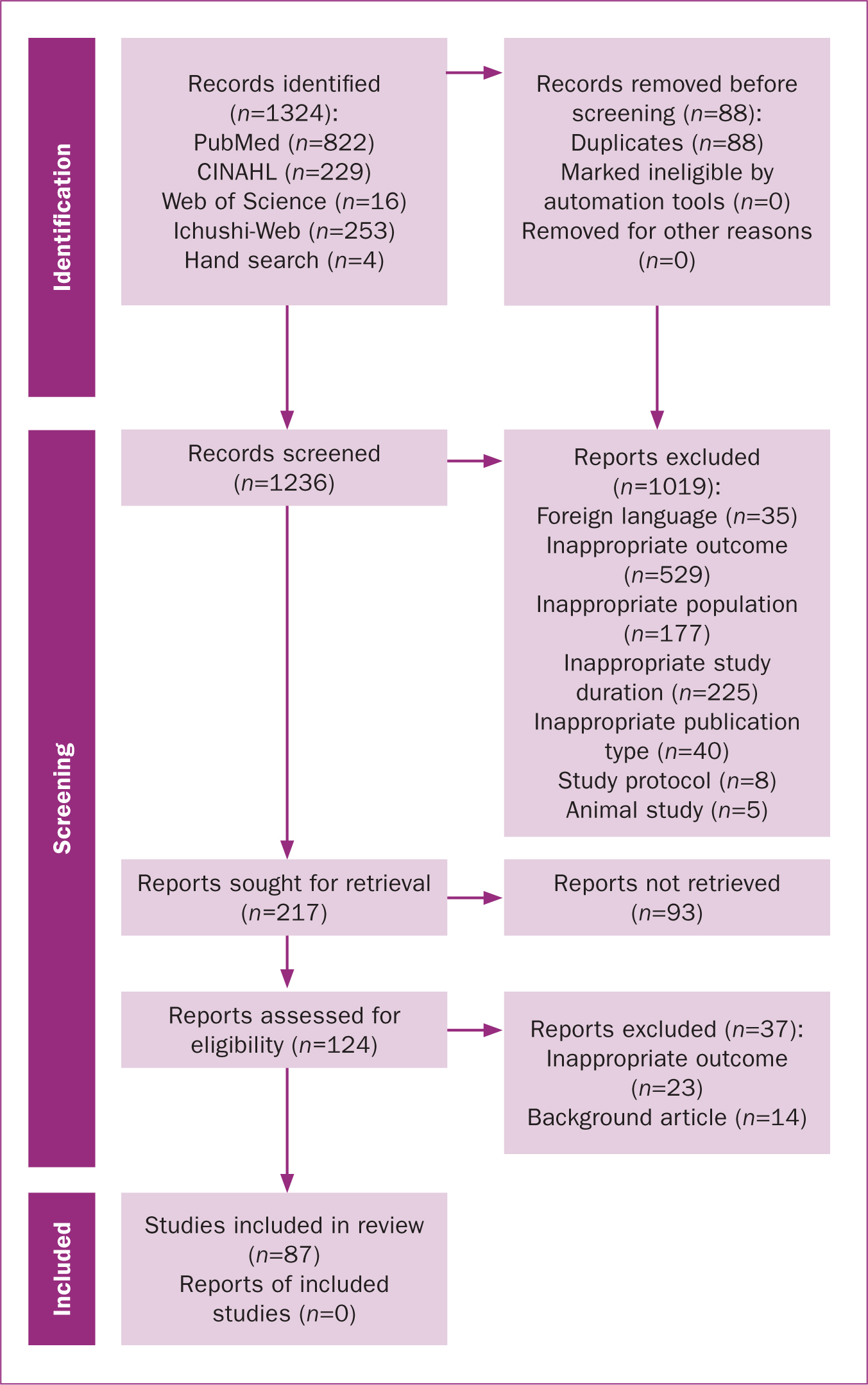

The inclusion criteria were studies published in English or Japanese after 2010 (this timeframe was selected because of changes in medical technology and social conditions after this point) where care was received from a midwife during birth, exploring the woman's perspective and experience of midwifery care. Articles where the care implemented by the midwife was not intended for the woman or that included other care providers than midwives were excluded, as were protocols, proceedings of academic societies and all other article types that were not primary research or literature reviews. Articles were selected for inclusion based on screening the title, abstract and full text (Figure 1).

Screening and analysis

Based on the definitions of antecedents, attributes and consequences outlined in Rodgers and Knafl's (2000) concept analysis, a coding sheet was developed. Descriptions of the antecedents that preceded intrapartum midwifery care, its attributes and consequences were extracted from each of the included studies.

Four researchers with maternal nursing and midwifery-related clinical experience and research knowledge discussed the process to ensure face validity by confirming the indicators for accurate extraction of the care assessment. AT conducted the primary data extraction, followed by a discussion of the validity of the extraction and construct concepts by the four researchers (AT, NO, NH, JM). In cases of disagreement, each of the four researchers reviewed the descriptions in the original literature and discussed them again. Quality appraisal was not performed so as to extract a broad range of concepts.

Results

A total of 1324 references were retrieved from the four databases. After removal of duplicates and screening based on the eligibility criteria, 87 studies were selected; 44 were qualitative, 33 were quantitative, 5 were mixed-methods studies and 5 were literature reviews (Table 1; Figure 1).

The identified components of intrapartum midwifery care are shown in Figure 2. Seven attributes, five antecedents and eight consequences were identified.

Antecedents

Five antecedents (factors preceding women's perception of intrapartum care) were identified: sociocultural background, antenatal preparation, midwives’ performance during birth, medical interventions during birth and midwives’ qualifications.

Women's sociocultural background influenced their perception of intrapartum care, including their ethnicity, economic status, insurance coverage and whether they shared a language with their midwife. Ethnicity and socioeconomic status can influence the incidence of discrimination and abuse during intrapartum care (Hastings-Tolsma et al, 2018; Mselle et al, 2019; Basile Ibrahim et al, 2021; Toker et al, 2021).

Women's expectations of labour and birth, knowledge of pregnancy (participation in antenatal classes), previous childbirth experiences and hopes and images of childbirth were highlighted as antenatal preparation that influenced intrapartum midwifery care (Aannestad et al, 2020; Hildingsson et al, 2021).

Factors affecting midwives’ performance during childbirth included the type of care provided, medical intervention status, time and mode of birth, pain status, pain relief methods, sanitary environment and the baby's health condition during labour. These experiences and perceptions could influence women's anxiety and fear during birth, as well as their perceptions of care (Leap et al, 2010; Namujju et al, 2018).

Medical interventions during birth, including emergency caesarean section, episiotomy, induced labour and instrumental birth, were associated with fear and incidents of rudeness, abuse and coercion (Otley, 2011; Mselle et al, 2019). Conversely, midwives’ qualifications, diligence and knowledge were linked with increased trust and security for women during birth (Hosseini Tabaghdehi et al, 2020; Toker and Aktaş, 2021).

Attributes

Seven attributes of women's perceptions of intrapartum care were identified. Having their needs fulfilled by caregiving during labour and birth empowered women to believe in their own strength. This encouraged women to trust midwives, making them feel warm and safe and protecting their dignity. Midwives helped women to understand their situation and supported them in making decisions. Such care helped them cope with labour and birth.

Midwifery care that fulfilled women's needs encompassed their particular needs being understood (Hosseini Tabaghdehi et al, 2020), care being provided when women desired it (Hajizadeh et al, 2020), midwives being there for them with or without support (Aannestad et al, 2020) and having enough time for them (Mutabazi and Brysiewicz, 2021). Women felt empowered when midwives believed in their strengths (Larsson et al, 2020) and actively encouraged them (Thies-Lagergren and Johansson, 2019).

The attribute ‘warmth’ included being treated comfortably by the midwife (Fumagalli et al, 2021; Haller et al, 2021), midwives having an empathetic attitude (Aktaş and Aydın, 2019), feeling protected as they became a mother and being accepted as they were (Aannestad et al, 2020). Similarly, ‘reassurance’ encompassed women feeling they could trust midwives (López-Toribio et al, 2021), and not feeling confused, anxious (Patterson et al, 2019; Toker and Aktaş, 2021), afraid (Hildingsson et al, 2021) or alone (Toker and Aktaş, 2021).

The attribute ‘protection of dignity’ indicated that women did not experience abuse, such as violence or unauthorised medical procedures (Baranowska et al, 2019; Hajizadeh et al, 2020; López-Toribio et al, 2021). It also included there being no discrimination as a result of sociocultural background (Hajizadeh et al, 2020; Basile et al, 2021) and their privacy being protected (Afaya et al, 2020; Basile Ibrahim et al, 2021).

‘Determination support’ indicated that women's choices were implemented based on their wishes, with adequate explanations of care; that they were supported in understanding their situation and care (Lazzerini et al, 2020; Basile Ibrahim et al, 2021); and that their progress and events were fully explained each time they occurred (López-Toribio et al, 2021; Mutabazi and Brysiewicz, 2021).

The phrase ‘control support’ indicated that women were able to express their wishes to the midwife regarding posture, what they did while in the labour and delivery room and pain management during labour and birth (López-Toribio et al, 2021; Mutabazi and Brysiewicz, 2021). It included that the woman's choice of support person/people was enabled (López-Toribio et al, 2021; Mutabazi and Brysiewicz, 2021) and that their cultural and religious preferences were respected (Mselle et al, 2019). Furthermore, it was classified as not being persuaded, manipulated or threatened by the midwives (Vedam et al, 2019) or forced into recommended care (López-Toribio et al, 2021).

Consequences

The consequences of intrapartum care included having a sense of self-control, feeling safe, secure and cared for with respect, having a positive experience and not feeling depressed, anxious or fearful.

Intrapartum care was able to give women a sense of self-control, and that they could cope with labour and childbirth (Sjöblom et al, 2014). Positive care allowed women to feel safe and secure (Dahlberg et al, 2016; Mselle et al, 2021) and were being treated as a valued human being (Afulani et al, 2017), which reduced anxiety or fear (Khwepeya et al, 2018; Baranowska et al, 2019).

Childbirth satisfaction was high when women could make their own decisions, have her needs met, feel safe and trust her midwives (Dupont et al, 2020; Hajizadeh et al, 2020; Hosseini et al, 2020; Larsson et al, 2020). Low satisfaction was the result of feeling insecure or fearful and experiencing violence, discrimination or coercion from midwives (Hosseini et al, 2020; Larsson et al, 2020; Fumagalli et al, 2021; Mutabazi and Brysiewicz, 2021).

Memories of childbirth were associated with postpartum mental health and were likely to be influenced by experiences of pain and strong emotions during the birth. Depression after childbirth was associated with anxiety, fear, violence and coercion during the birth (Elmir et al, 2010).

Discussion

This study identified seven attributes of intrapartum midwifery care from a woman's perspective, as well as five preceding factors and seven outcomes.

Women who received care and information tailored to their needs from midwives tended to be more satisfied with their childbirth experience (McLachlan et al, 2016; Larsson et al, 2020) and had more positive experiences (Lawal et al, 2024). Midwives who encouraged women and believed in their strength helped empower women to overcome difficulties during childbirth, giving them a sense of achievement and satisfaction (Maputle, 2018; Thies-Lagergren et al, 2019).

‘Warm’ care that made women feel comfortable, as they were treated with empathy and looked after during the process of becoming a mother. Birth causes physical and mental changes, as well as pain, for women. Receiving warm care enabled women to accept themselves as they are (Shareef et al, 2023). This attribute is a newly identified characteristic of care during childbirth and should be incorporated in education and emphasised in practice.

Women's understanding during birth was supported by sufficient explanations of their options and situation. As these constantly change during birth, being provided with information about the current situation and available options enabled women to make decisions (Hajizadeh et al, 2020; Hosseini et al, 2020). This increased their sense of self-control, leading to a positive experience (Aannestad et al, 2020; Hajizadeh et al, 2020). During childbirth, women entrust themselves and their care to others; therefore, it is essential that they understand the situation and feel a sense of self-control (Afaya et al, 2020; Shareef et al, 2023).

Intrapartum midwifery care is influenced by a woman's sociocultural background (Olza et al, 2018), preparation before childbirth and the midwife. The sociocultural background of women and their antenatal preparation were shown to be antecedent factors for intrapartum midwifery care. Factors relating to midwives, such as their work environment, workload and staffing (Thompson, 2001) can impact the care they provide. Midwives who demonstrate diligence and extensive knowledge are more likely to create a positive care experience for women (Sjöblom et al, 2014; Borrelli et al, 2016).

Multiple factors were found to impact the outcomes of intrapartum care, including having a sense of self-control, feeling safe and secure, being cared for with respect, having no anxiety or fear, having a positive experience and memories and not feeling depressed. The relationship between preceding factors and consequences forms a conceptual model of midwifery care (Figure 2). The attributes of care can indicate high- or low-quality midwifery care, leading to positive or negative outcomes. Several scales evaluate satisfaction with childbirth as a measure of quality of care (Dencker et al, 2012; Truijens et al, 2014; Dwekat et al, 2021). However, satisfaction is not the only factor when considering the quality of midwifery care; it is more appropriate to consider it a result of the care.

Implications for practice

Scales have been developed to evaluate the quality of intrapartum midwifery care (Heaman et al, 2014; Truijens et al, 2014; Scheerhagen et al, 2019; Dwekat et al, 2021). However, none of these scales include all the attributes found in this review. Developing a scale based on the concepts found in this review may allow for objective evaluation of the quality of midwifery care from the perspective of women. Women are best placed to understand their own lives, thoughts and emotions during childbirth (Thompson, 2001; Olza et al, 2018); improving the quality of midwifery care from a woman's perspective may contribute to better and more positive childbirth experiences that could be adapted across cultures.

Strengths and limitations

This review organised and defined the concept of intrapartum midwifery care from a woman's perspective and proposes a new model for this concept. However, this review was a conceptual analysis of literature in English and Japanese. Further research is required to determine whether the concept can be applied to all cultures.

Conclusions

Intrapartum midwifery care during childbirth was described as meeting women's needs, empowering them, making them feel warm, giving them a sense of security, protecting their dignity, supporting their decisions and supporting their sense of control.