Good nutrition during the first 1000 days of life (from the point of conception to a child's second birthday) has an important influence on an individual's future. It is a critical period for growth and development, and any harm caused by inadequate nutrition can influence health for an individual's whole lifetime (United Nations Children's Fund (UNICEF), 2016). Therefore, good nutrition during pregnancy is of utmost importance in achieving optimal health for individuals and populations globally. During the first 1000 days of life, nutrition quality can influence the prevalence of non-communicable disease later in life. Barker's (1995) hypothesis stated that low birth weight (reflecting poor nutrition in utero) was associated with an increased lifetime incidence of cardiovascular disease, stroke and type 2 diabetes, suggesting that the nutrient environment of early life could permanently alter gene expression.

The World Health Organization (WHO, 2016) acknowledges that good nutrition during early life is the most important factor in managing the burden of disease and health inequalities worldwide. They emphasise that poor nutrition during early life, including pregnancy, can have detrimental short-and long-term effects. As non-communicable diseases are now the leading cause of premature death and disability worldwide, imposing a significant burden on national health services, finding health interventions that reduce such burdens is urgently required (WHO, 2016).

Globally, 161 million children under the age of 5 years old are chronically undernourished (stunted), and 51 million are acutely undernourished (wasted), while 42 million are reported to be overweight (UNICEF, 2016). Undernutrition during pregnancy is strongly associated with stunted growth in childhood, significantly restricting physical and mental development. Therefore, promoting good eating habits and optimising maternal nutritional status and gestational weight gain will reduce nutritional deficiencies during pregnancy and lower the risk of adverse pregnancy outcomes associated with undernutrition and the development of non-communicable diseases (UNICEF, 2016; WHO, 2016).

The UK and Brazil

Both the UK and Brazil have sizeable populations that mean there is high demand for antenatal and maternal care. A comparison of maternal demographic data from Brazil and the UK is shown in Table 1.

| Brazil | UK | |

|---|---|---|

| Population | 208 million | 66 million |

| Life expectancy | 71 years (men) |

79 years (men) |

| Expenditure on health (% GDP) | 8.32 | 9.12 |

| Births attended by skilled health personnel (%) | 99 | 100 |

| Live births | 2 935 000 | 779 000 |

| Maternal mortality ratio per 100 000 | 60 (n=1700) | 7 (n=52) |

| Obesity (%) | 22 | 30 |

| Caesarean sections (%) | 55.5 | 18 |

Historically, Brazil has had significant problems with undernutrition, especially in children, although this has improved considerably in recent decades because of the rising quality of living standards (Wagstaff and Watanabe, 2000). This could explain the increased focus on nutrition during antenatal care that is seen in Brazil as compared to the UK.

Globally, the prevalence of micronutrient deficiencies remains high, although it is higher in low-income countries (UNICEF, 2016). In the UK, severe forms of undernutrition are rare (in the absence of other health problems); however, national surveys show that inadequate intakes of micronutrients remain a common problem (Public Health England (PHE), 2018). Several key micronutrients are associated with optimal fetal development (Table 2). A number of factors are associated with low birth weight, including genetics, ethnicity and living in an income deprived area. However, some aspects of a mother's life that are modifiable, such as avoiding alcohol and smoking and ensuring a nutritionally adequate diet, can reduce the risk of low birth weight (National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE), 2020).

| Nutrient | Role | Sources | Deficiency |

|---|---|---|---|

| Iron (British Dietetic Association (BDA), 2017a) | Make haemoglobin of red blood cells (mother and fetus); maintain healthy immune system | Red meat, poultry, eggs, pulses, beans, nuts, tofu, fortified breakfast cereal | Anaemia, tiredness, reduced immune response, breathlessness (adults and children) |

| Calcium (BDA, 2017b) | Make/maintain strong bones and teeth (mother and fetus); maintain healthy nervous system | Milk, cheese, yoghurt, white bread, oranges, fortified soy products (milk, yoghurt), most plant milk (fortified) | Osteoporosis (adults); rickets (children) |

| Iodine (BDA, 2019a) | Make thyroid hormone (mother and fetus); brain development (fetus) | Milk, yoghurt, sea fish, some plant milks are fortified but not all (important to check) | Goitre (adults); poor brain development, mental retardation, reduced IQ (fetus/children) |

| Omega 3 fatty acids (BDA, 2017c) | Cardiometabolic health (mother); brain and neurological development (fetus) | Oily fish, walnuts, pumpkin seeds, rapeseed oil, soya and soya products | Increased risk of cardiometabolic disease (adults); poor brain and neurological development (fetus/children) |

| Vitamin D* (BDA, 2019b) | Make/maintain strong bones, muscles and teeth (mother and fetus); maintain healthy immune system | Sunlight on skin, oily fish, egg yolk, fortified breakfast cereal, margarine, milk and yoghurt (fortified) | Osteomalacia (adults); rickets (children) |

| Folic acid (BDA, 2019c) | Support rapidly developing spine and nerve cells in early pregnancy (fetus); reduced risk of cardiometabolic disease (mother) | Green leafy vegetables, beans, oranges, wholegrains, poultry, pork and fortified foods (bread/breakfast cereal) | Macrocytic anaemia; neural tube defects (fetus); increased risk of cardiometabolic disease (adults) |

The importance of nutrients

Multiple micronutrient deficiencies in pregnant women can adversely affect fetal metabolic programming, restricting growth and development and increasing mortality (WHO, 2016).

Iron deficiency anaemia, the most prevalent nutrient deficiency globally, affects 500 million people, including 38% of pregnant women (NICE, 2021). During preconception or early pregnancy, anaemia is related to poor fetal development, low birth weight or pre-term delivery (WHO, 2016). During pregnancy and early childhood, iron deficiency adversely affects brain development and cognitive function; for example, it is associated with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder and/or autism in children (Pivina et al, 2019). Areas of the body with high metabolism require more iron and so have increased risk of dysfunction with iron deficiency. In utero, the fetal brain is developing rapidly and poor maternal iron intake has been associated with abnormal brain structure at birth, and with autism and schizophrenia in later life (Georgieff, 2020).

Maternal vitamin D and calcium also play an important role and deficiencies in these nutrients are associated with poor fetal bone development, pre-eclampsia, pre-term birth and small-for-gestational-age babies (WHO, 2016).

Iodine deficiency is thought to be the chief cause of preventable brain damage worldwide; it is vital for producing thyroid hormones, fetal brain development, growth, and metabolism (WHO, 2016). Even a minor iodine deficiency during pregnancy (defined as urinary iodine-to-creatinine ratio of <150μg/g) is associated with reduced IQ in offspring, and subsequent optimal iodine intakes do not improve this adverse effect during childhood (Bath et al, 2013; Hynes et al, 2013).

Omega-3 fatty acids, particularly docosahexaenoic acid, are well known for promoting fetal brain and neurological development (British Dietetic Association (BDA), 2017c). Poor maternal omega-3 status is also associated with increased risk of gestational diabetes and pre-eclampsia; both of which are potentially responsible for reduced placental transfer of omega-3 to the fetus, imposing short-term and long-term impacts on brain health (Devarshi et al, 2019).

Folate has a key role in fetal development, responsible for cell division, tissue growth and amino acid metabolism (BDA, 2019c). Supplementation during preconception and early pregnancy protects against fetal neural tube defects, while evidence is emerging that later supplementation (during the second and third trimesters) may positively affect child IQ (McNulty et al, 2019). Table 2 shows further details regarding key micronutrients.

Nutrition and pregnancy

Healthcare professionals may assume that adequate (or over adequate) gestational weight gain indicates adequate (or over adequate) nutritional intake, but this is not necessarily the case. Those from low-income households may have no choice but to consume cheap, energy-rich, but low-quality food (Joseph Rowntree Foundation, 2016).

The UK National Diet and Nutrition Survey (PHE, 2018) shows that on average, UK women of childbearing age (19–49 years) are deficient in several key micronutrients, including iron, calcium and iodine, with 27%, 11% and 15% achieving less than the lower reference nutrient intake (Committee on Medical Aspects of Foods, 1991), respectively. Research on pregnant women living with obesity in the UK reveals a more negative picture. Despite having a body mass index >35kg/m2, 18–31% achieved intakes lower than the lower reference nutrient intake (8mg) for iron and 8–18% achieved lower than the intake (69.9µg/d) for iodine (Charnley et al, 2021).

Iron, calcium and iodine are essential micronutrients for a healthy pregnancy and optimal fetal development. Pregnant women living with obesity (body mass index>30kg/m2) are also at risk of having a poor-quality diet deficient in key micronutrients, demonstrating that conversations about healthy eating are crucial for all pregnant women, regardless of body mass index (Charnley et al, 2021). There is a need to focus on maternal dietary quality, as well as quantity, to promote health in this and future generations.

The Brazilian approach to promoting healthy eating.

In Brazil, the Ministry of Health has produced a significant collection of guides and manuals on healthy eating, with the objective of promoting health through balanced eating. Such documents are intended for both the population in general and healthcare professionals, such as midwives.

The recent publication ‘demystifying doubts about food and nutrition - support material for healthcare professionals’ (Ministério da Saúde (MS), 2016a) aims to guide and subsidise professionals’ practice, as well as expand the autonomy of people, families and communities, facilitating access to knowledge about food and nutrition. In the state of São Paulo, the State Department of Health produced the document ‘care line - pregnant and postpartum women’ (Secretaria de Estado da Saúde de São Paulo, 2018). The document elaborated on the objective of improving the organisation of assistance to women during pregnancy, childbirth and the puerperium through articulation between different levels of care and services. It also discussed the importance of nutritional counselling and providing support for guidance by the professional.

Food guides help the population to make healthier and more appropriate food choices, which in a country like Brazil, can be very challenging. Brazil has a population that is not only amalgamated, but also heterogeneous in terms of food culture and the most prevalent health problems in each region of the country. According to Pinheiro (2001) and Abreu et al (2001), Brazilian eating habits were formed from the merger of Indigenous, Portuguese and African cuisines, which over time acquired their own characteristics and peculiarities. Each region has developed a rich and diversified popular culture, with its own cuisine, as a result of the influence of migratory currents and adaptations to the climate and availability of food.

For many years, undernutrition and its related conditions represented one of the main health problems needing management in Brazil. In the last 25 years, the country has experienced the double burden of malnutrition, with undernutrition still prevalent (especially in children), alongside obesity and being overweight. The incidence of increased weight continues to advance in the population in general (MS, 2019a). This diversity within the country, when considered in public policies related to food, requires approaches for each region. It is for this reason that the food guide for the Brazilian population (MS, 2014) provides specific guidelines for each region regarding food consumption.

Although the food guide is an important technology to guide the work of health professionals in nutritional care in the unified health system, its use in daily health services can be greatly enhanced. The Ministry of Health has committed to producing materials and collective educational actions to disseminate the food guide in the context of primary healthcare. Among the most recent publications are the ‘instruction manual: implementing the food guide for the Brazilian population in basic health care teams’ (MS, 2019a), published in 2019, and the first issue of the ‘protocols for using the food guide for the Brazilian population in guidance food: theoretical-methodological bases for the adult population’, published in 2021 (MS, 2021).

For midwives caring for women during pregnancy and the puerperium, in 2019, the Brazilian Ministry of Health published recommendations and information on feeding children in the first 2 years of life, ‘the food guide for Brazilian children under 2 years’. It focuses on breastfeeding, aiming to promote children's health, growth and development. The document also supports professionals in the development of food and nutrition education on an individual and collective level in the unified health system and other sectors (MS, 2021).

Despite these initiatives, Brazil lacks guides aimed at pregnant women and/or the postpartum period. The only official initiative offering nutritional guidance for pregnant women is the ‘pregnancy booklet’ (MS, 2016b), produced by the Ministry of Health in conjunction with the state, municipal and federal secretariats. This booklet is distributed free of charge at all basic health units and covers several important subjects, besides healthy eating in pregnancy, such as rights before and after childbirth, tips for a healthy pregnancy and warning signs, information and guidance on pregnancy and baby development, childbirth and the postpartum period (MS, 2019b).

The booklet suggests 10 steps for healthy eating during pregnancy:

This set of instructions is simple enough to be guided by any healthcare professional, and easily understood by the general population. There is an emphasis on avoiding micronutrient deficiencies (points 4, 5 and 9), particularly iron. Most prenatal consultations, to monitor a mother's weight gain and health status and the fetus’ development, will be performed by doctors, nurses or midwives, and the mother will be referred to a nutritionist only if necessary. Therefore, in Brazil, any healthcare professional, including midwives, are capable of providing nutritional guidance to health service users.

UK midwives: healthy eating and weight management during pregnancy

Recent years have seen the increased expectation that many UK healthcare professionals can deliver health promotion messages to service users. ‘Making every contact count’ (PHE, 2016) encourages healthcare professionals to use the ‘millions of day-to-day interactions’ they have with service users to promote healthier lifestyles by encouraging physical activity and healthy eating (PHE, 2016). Several guidelines by NICE highlight the role of healthcare professionals as key providers of nutrition and healthy eating advice. For example, antenatal care guidelines (NICE, 2017) state that midwives should discuss nutrition, diet and vitamin supplementation at booking-in appointments.

The public generally considers doctors and other healthcare professionals as ‘very credible’ sources of nutrition information, but training on nutrition is usually limited for UK healthcare professionals (Wongvibulsin et al, 2017), including midwives. Midwives are reported to check if women are taking folic acid supplements, give advice about food hygiene and sometimes signpost women to sources of further information about nutrition during antenatal appointments, but this is often inconsistent and may include signposting to unreliable sources (McCann et al, 2018).

In 1995, Mulliner et al (1995) reported that 86% of 77 registered midwives in the UK had no formal nutrition education, 46% scored poorly in a nutrition knowledge questionnaire and 75% felt unqualified to advise pregnant women about nutrition. Olander et al (2011) more recently reported that UK healthcare professionals lacked the knowledge and confidence to advise pregnant women regarding healthy weight during and after pregnancy. This does not appear to have improved in recent years. McCann et al (2018) found that none of the UK midwives they interviewed had received any nutrition or weight management training, and consequently lacked the confidence and skills to deliver any in-depth advice to pregnant women. Moreover, pregnant women recognised that the advice they received from midwives lacked depth and failed to meet their needs (Abayomi et al, 2020).

The current UK midwifery syllabus should provide a professional, holistic, evidence-based programme, centred on a public health curriculum. It aims to prepare midwifery students for safe and effective practice, so that at the point of registration, they can assume full responsibility and accountability for their practice as midwives (Nursing and Midwifery Council (NMC), 2009). The NMC (2009; 2018) provides guiding principles for professional midwifery knowledge, skills and competence. The underpinning philosophy of undergraduate midwifery education is the provision of individualised care for women and families via a public health framework to reflect the wider public health role of the midwife (National Maternity Review, 2016; Department of Health, 2020). Women's overall health and wellbeing throughout the childbearing continuum is a thread of contemporary midwifery practice, with nutrition forming an important element of care (Elia and Stewart, 2005). Despite this, the public health and nutrition aspects of most UK midwifery programs are delivered by midwifery staff with limited nutrition expertise, resulting in a dilution of key messages. Following registration, very few UK midwives receive any additional training or updates about nutrition (McCann et al, 2018).

The importance of healthy gestational weight gain

Optimal gestational weight gain is known to be a key influencing factor regarding the health of offspring. The WHO (2016) reports an increased risk of obesity and comorbidities in individuals whose mothers had a high body mass index (>30kg/m2), had excessive gestational weight gain or were poorly nourished (multiple micronutrient deficiencies) during pregnancy. In the UK, NICE (2010) suggested that 1 in 1000 UK pregnancies are complicated by women living with severe obesity (body mass index >50kg/m2).

Despite an increase in the prevalence and severity of obesity in pregnancy (NICE, 2010), the UK currently does not have any gestational weight gain recommendations. NICE (2010; 2017) guidelines focus on referral to weight management services postpartum, and the Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists (2018) acknowledges a lack of consensus on recommendations for gestational weight gain targets. In the absence of specific gestational weight gain recommendations, healthcare professionals in the UK often refer to USA Institute of Medicine (IOM, 2009) guidelines for gestational weight gain, where weight gain is recommended according to pre-pregnancy body mass index (Table 3).

| Pre-pregnancy BMI (kg/m2) | Recommended gestational weight gain (lb) | Recommended gestational weight gain (kg) | Mean gestational weight gain per week (kg) |

|---|---|---|---|

| <18.5 | 28–40 | 12.5–18 | 0.51 |

| 18.5–25 | 25–35 | 11–16 | 0.42 |

| 25–30 | 15–25 | 6–11 | 0.28 |

| >30 | 11–20 | 5–9 | 0.22 |

The gestational weight gain range for individuals according to their body mass index category is associated with optimal birth weight (American College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists (ACOG), 2013). However, the data used to determine these guidelines are now somewhat dated and precede the substantial prevalence of maternal obesity. More recent research suggests that avoiding any additional gestational weight gain, when pre-pregnancy women are living with obesity (BMI>35kg/m2), may offer protection against adverse pregnancy outcomes (Narayanan et al, 2016). Cassidy et al (2018) found women living with a healthy to overweight weight status (body mass index: 20–29.9kg/m2) were more likely to have gestational weight gain in excess of IOM recommendations. Women with a pre-pregnancy weight within the healthy range (body mass index: 20–24.9kg/m2) and who experienced excessive gestational weight gain, were more likely to need an assisted birth, compared to those with lower weight gain.

A systematic review and meta-analysis of 1 309 136 pregnancies' gestational weight gain, reported a higher risk of adverse maternal and infant outcomes, who gained above or below the IOM guidelines. Of these women, 47% had weight gain greater than IOM recommendations and 23% had less (Goldstein et al, 2017). These data highlight the need for appropriate support and intervention to help women manage gestational weight gain, as appropriate to their initial and changing weight needs, during pregnancy.

Gestational weight gain management in the UK and Brazil

Gestational weight gain may be more influential regarding adverse pregnancy outcomes than pre-pregnancy weight status (body mass index alone), highlighting the need for both monitoring of weight change and weight management advice for all during pregnancy. However, UK women are only routinely weighed at their first antenatal appointment. NICE (2010) recommends avoiding routine weighing beyond the initial appointment (unless clinical management can be influenced or if nutrition is a concern). The RCOG (2018) recommends weighing pregnant women living with obesity in the later stages of pregnancy, but this is for birth planning (equipment needs), as opposed to consideration of nutritional and dietary needs.

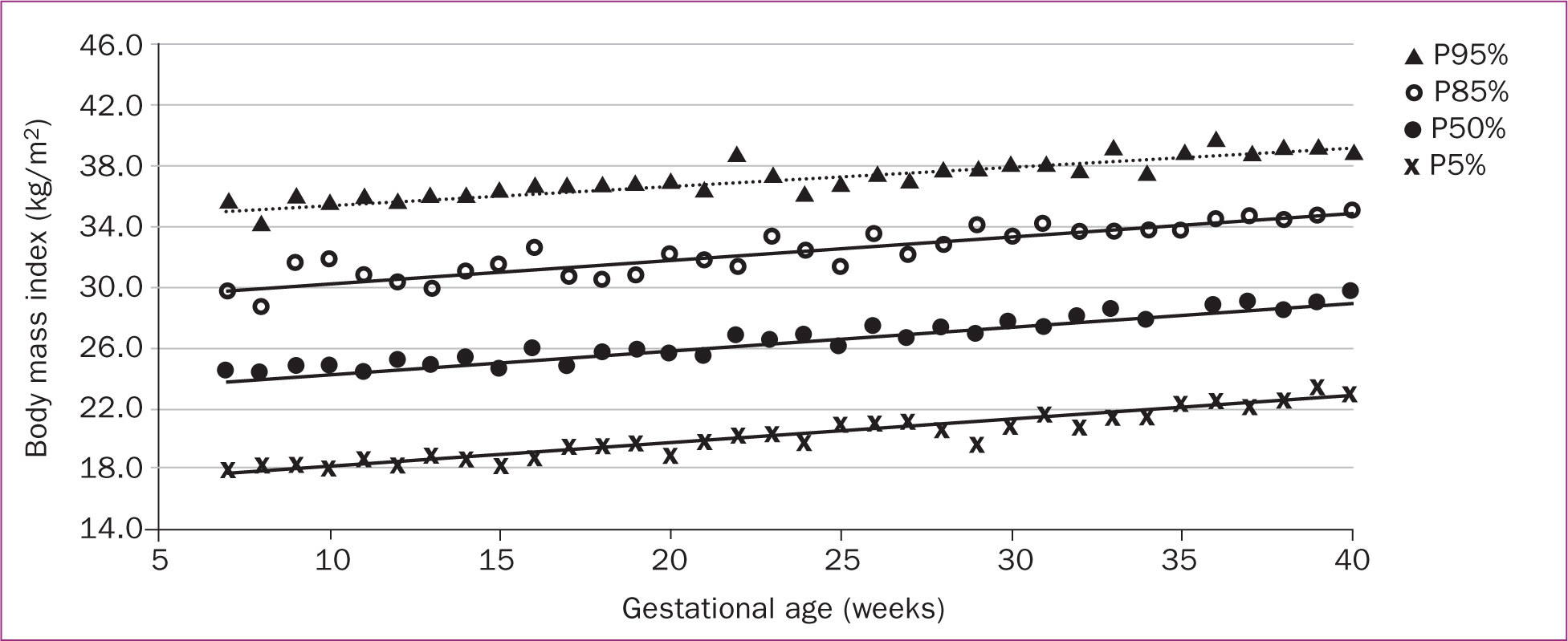

In Brazil, gestational weight gain is routinely monitored throughout pregnancy. Although Brazil has not developed its own reference curve for body mass index values for gestational age, healthcare professionals use an assessment of the pregnant woman's nutritional status according to pre-pregnancy body mass index, then refer to Atalah's curve (Atalah et al, 1997), which is based on IOM recommendations (Figure 1).

As directed by the Brazil pregnancy booklet, the healthcare professional should record data from prenatal consultations, such as vaccines and/or tests, as well as the height and weight of the woman in all prenatal consultations, to monitor and evaluate gestational weight gain. During the first antenatal consultation, health professionals are advised to use Atalah's curve (Figure 1) to estimate optimal weight gain in the first trimester and then each week from the second trimester until the end of pregnancy. This information is shared with the pregnant woman, to encourage her to actively participate in monitoring her health and pregnancy development.

Adequate monitoring allows the health professional to identify pregnant women at nutritional risk (underweight, overweight or with obesity) early in pregnancy, detect low or excessive weight gain and outline the appropriate guidance for each case, aiming for optimal maternal nutritional status, conditions for birth and offspring birth weight (Atalah et al, 1997). By offering this assistance, midwives play a fundamental role and have the chance to positively influence healthy eating habits at a time when women are highly motivated (MS, 2006). This orientation during pregnancy not only improves the likelihood of a favourable birth outcome (a healthy baby), but also the management of gestational weight gain throughout trimesters. As gestational weight gain is an important indicator of maternal and fetal health, it is essential to train midwives capable of contributing to the proper management of weight gain in this phase.

Midwifery training on nutrition in Brazil

In Brazil, nutritional guidance for healthy individuals can be given by any healthcare professional. Including content related to nutrition is viewed as essential for midwives, who are trained to contribute to the development of healthy behaviour during pregnancy. The only course that trains midwives in Brazil is at the University of São Paulo, where the curriculum covers semi-annual subjects in biological sciences, human and social sciences and health, in addition to clinical practices and curricular internships.

The curriculum's content on nutrition is discussed within different disciplines with varying degrees of depth. One of the first contacts a midwifery student will have with this subject is in ‘biological foundations of obstetrics III’, which discusses fundamental knowledge of the morphology, physiology and biochemistry of the digestive and urinary systems, in an integrated way.

Importantly, the nutrition aspects of the course were designed and are delivered by a nutritionist, ensuring that the content is up-to-date, relevant, scientific and evidence-based. This course is offered in the sixth semester of the programme, with a total workload of 60 hours and four credits, so that students can learn about the main topics related to nutritional guidance (Table 4).

| Topic | Subject |

|---|---|

| 1. Factual | Introduction to nutrition, behaviour and eating habits, biochemical composition of food and milk and nutritional needs during pregnancy and lactation |

| 2. Conceptual | Breastfeeding, nutritional status of pregnant women, nutritional education and public policies in nutrition |

| 3. Procedural | Assessment of nutritional habits, assessment and nutritional guidance in the context of pregnancy, search and update on official documents and national and international guidelines, related to nutrition in the context of the discipline |

| 4. Attitudinal | Empathy for colleagues and the population served in practice, respect for the food culture and socioeconomic status of others, respect for a woman's decision to breastfeed or not and to have a natural birth or not, respect for diversity of opinions |

Since its insertion in the curriculum, the discipline has integrated changes both in content, didactic strategies and in the academic period in which it is offered. Currently, the discipline is taught simultaneously to ‘assistance to women in prenatal and postpartum’ and ‘integrated curricular internship 1’, so that it allows undergraduates to study topics in nutrition at the same time that they encounter primary healthcare topics.

Throughout the semester, students work in groups, and the course includes exploring and resolving three clinical case studies. Each group agrees on management for the case study patient, within which topics studies at the beginning of the semester are developed. After elaboration of the cases, there are three opportunities for discussion with the whole class, where the material produced by each group is shared collectively. Following these presentations, the teacher explores a subject more deeply for synthesis.

This approach allows students to translate nutrition theory into the practice of prenatal and postpartum care. Opportunities for offering nutritional guidance are highlighted as relevant to both the outcome of a healthy pregnancy and for the baby's development in its early years. In doing so, midwives' confidence in their ability to advise women on healthy eating and weight management during pregnancy is strengthened.

Sharing best practice: learning from others

Optimal nutrition and gestational weight gain are both key to maternal and fetal health. Moreover, they are both modifiable risk factors for the prevention of poor health and non-communicable diseases. It is an ideal opportunity for healthcare professionals to intervene and encourage healthy eating habits. In the UK, most pregnant women do not have routine access to dietitians during antenatal care. In 2017, there were only 9469 registered dietitians in the UK (Health and Care Professions Council, 2017), compared to 26 778 registered midwives in England alone in 2020 (NHS Digital, 2020), so the role of encouraging healthy eating is largely left to midwives. This important midwifery role is acknowledged by the WHO (2016) and NICE (2017) and yet, UK midwives reported having no training on nutrition and healthy eating (McCann et al, 2018) and a lack of skills, confidence and knowledge in this area (Mulliner et al, 1995; Abayomi et al, 2020).

In contrast, pregnant women in Brazil have very limited access to midwifery care, with only one undergraduate programme for the population of 208 million people (WHO, 2017). However, undergraduate training includes comprehensive nutrition input, with an emphasis on translating theory into practical application. This means midwives are better prepared to support pregnant women in nutrition and healthy eating. Furthermore, nutrition experts design and deliver the nutrition content of course curricula for healthcare professionals.

Midwives in Brazil are confident talking to women about nutrition and weight gain during pregnancy. They weigh women regularly during antenatal care and plot their weight on Atalah's curve. They are then confident when they need to intervene with appropriate advice, should weight gain be inadequate or excessive. However, because of the severe shortage of midwives in Brazil, their influence on improvements to antenatal care has yet to be formally recognised or documented. Midwives in Brazil report that they do make a difference to the services where they are employed and that improvements in quality of care can be noticed (Narchi et al, 2017).

Conclusions

Optimal nutrition prior to and during pregnancy is essential for fetal and maternal health, while optimal gestational weight gain strongly influences birth weight and protects against non-communicable diseases. Midwives have a key role in interpreting and communicating key nutritional messages to pregnant women in their care, at a time when they are highly motivated to make changes. In the UK, midwives report a lack of training regarding nutrition, leading to poor skills and confidence in advising pregnant women about healthy eating and weight gain. In Brazil, there are more qualified nutritionists in the population and their expertise influences the training of other health professionals, including midwives. Brazilian midwives undertake in-depth education about nutrition throughout their undergraduate course, which is designed and delivered by a nutritionist. Moreover, there is an emphasis on translating nutritional messages into practice, ensuring that qualified midwives have the knowledge and skills they need to support pregnant women.

The Brazilian government is keen to increase the number of qualified midwives in the country, ensuring much needed improvements in maternal morbidity and mortality. Conversely, UK midwives could improve their practice, if the approach to nutrition education during training was made more similar to that of Brazil.

The UK could improve population access to dietitians/nutritionists by expanding education provision nationally. UK midwives would likely benefit from bespoke training regarding pregnancy-specific nutrition and healthy gestational weight gain, as part of their undergraduate/postgraduate training. UK dietitians and nutritionists could be more involved in the design and delivery of nutrition education to healthcare professionals, including midwives. Improved collaboration between dietitians/nutritionists and midwives, that encouraged sharing best practice, would help to ensure that pregnant women can access optimal care and advice about nutrition and gestational weight gain during antenatal care.