The World Health Organization (WHO, 2020) recommends exclusive breastfeeding, which is defined as providing a child with breast milk as the only form of sustenance, for the first 6 months of life. Researchers on breastfeeding have largely distinguished between mothers who intend to exclusively breastfeed and those who do not, reporting that breastfeeding duration is shorter in those who decided to only ‘try’ breastfeeding out of a sense of obligation, when compared to mothers committed to exclusive breastfeeding (Nesbitt et al, 2012). However, intentions to breastfeed are complex and some mothers decide to feed using a combination of breast milk and breast milk substitute. This can lead to shorter breastfeeding duration and a reduced likelihood of meeting breastfeeding goals (Chezem et al, 2003), increased levels of guilt and dissatisfaction with feeding choice in mothers of babies under 26 weeks of age (Komninou et al, 2017) and an increased risk of obesity when the child reaches school age (Rossiter et al, 2015). This illustrates that mixed feeding can have important implications for both mother and child. Cabieses et al (2014) conducted a multi-methods study and found that mothers who intended to mixed feed reported that their intention was influenced by the health benefits of breastfeeding and the convenience of bottle feeding. Further research is required to more fully understand the reasons behind intentions to mixed feed.

The theory of planned behaviour (Ajzen, 1991) proposes that intention predicts behaviour and that intentions are influenced by three contributing factors: attitudes, social norms and perceived behavioural control. Authors of a meta-analysis reported the theory of planned behaviour variables to be significant predictors of breastfeeding intention and that intention was a significant predictor of breastfeeding behaviour (Guo et al, 2016). Interventions based on the theory can successfully increase breastfeeding intentions (Giles et al, 2014), illustrating the value of these constructs for influencing intention. However, the inclusion of additional variables, including postpartum support and perceived breastfeeding difficulty, improves the explanatory power of the theory of planned behaviour (Tengku Ismail et al, 2016) and breastfeeding knowledge has been shown to be the greatest contributor to exclusive breastfeeding behaviour, followed by the theory's variables (Zhang et al, 2018).

Box 1.Case study pen portraitsOlivia was 22 years old and 24 weeks pregnant. During pregnancy, Olivia had been experiencing hyperemesis gravidarum. Olivia expressed that she had been bottlefed as a child.Chloe was 23 years old and 30 weeks pregnant. Chloe came from a big family with all of her siblings already having children. Chloe was on furlough because of the COVID-19 pandemic at the time of the interview and was feeling restricted and keen to get back to work.Lucy was 25 years old and 37 weeks pregnant. Lucy was beginning to find pregnancy uncomfortable and was working long shifts in a physically demanding care worker role. Lucy was looking forward to starting her maternity leave.Alice was 25 years old and 28 weeks pregnant. Alice explained that this was a surprise pregnancy as they had not been trying to conceive. Alice experienced a lot of morning sickness in early pregnancy.

Although there have been improvements in breastfeeding rates, the UK still has some of the lowest breastfeeding rates in the world, with only 33% of babies receiving any breast milk at 6 months and less than 1% receiving any at 12 months (Brown, 2016a). Breastfeeding has become a public health priority (Newman and Williamson, 2018) and in the UK schemes including the NHS ‘Start for Life’ and the Baby Friendly Initiative aim to encourage and facilitate breastfeeding (Brown, 2016b). Gaining an understanding of why women plan to mixed feed is highly important because it will inform the development of interventions to promote breastfeeding. There is evidence that the theory of planned behaviour provides a strong theoretical base for investigating infant feeding intentions. Therefore, in this study, a qualitative approach guided by the theory's constructs (Ajzen, 1991) was used to explore the factors that influenced pregnant women's intentions to mixed feed their first child.

Methods

An in-depth idiographic multiple case study (Eatough and Shaw, 2017) grounded in a ‘subtle realist’ (Hammersley, 1992) epistemology was employed. Case study research involves empirical enquiry to investigate a contemporary phenomenon in depth within its real-life context, with conclusions drawn from several cases being more powerful than those drawn from a single case (Yin, 2009). The purpose of this form of research is to represent reality rather than reproduce it (Hammersley, 1992) and aims for selective representation of a phenomena rather than generalisable reproduction of ‘truths’. Idiographic qualitative research approaches are ideal for building theory grounded within human experience-in-context, in addition to enabling the testing of existing theory, such as the theory of planned behaviour, against new data (Willig, 2019). Idiographic designs are committed to detailed examination of individual cases exploring the how, why and what of phenomena, and therefore neccessitate small samples (Smith and Osborn, 2015).

Sample

The research was carried out with women pregnant with their first child living in the UK, who were over the age of 18 and intended to mixed feed. They were invited to take part in this study to explore mothers' infant feeding intentions and the potential influences on these intentions. The participants were recruited using opportunistic sampling through advertisements on social media platforms and parenting forums. No compensation or payments were made to participants. This study used four case studies in line with recommendations for 4–5 participants in case study research (Creswell, 2013).

Data collection

Data were collected in the first half of 2020 by the third author as part of her MSc dissertation research. One interview was conducted face to face and the remainder online because of COVID-19 restrictions in England. Semi-structured interviews (Flick, 2009) were guided by a schedule based on the theory of planned behaviour. The schedule aimed to elicit thoughts and ideas regarding the factors contributing to feeding intentions using the theory, while allowing flexibility to identify additional factors. Participants were engaged with interviews lasting up to 1 hour.

The research team played an active role in the construction of the analysis. To address this, reflexivity is essential, and the role of the researcher must be acknowledged and demonstrated when reporting qualitative research (Willig, 2008). To address this, the context of the research team was noted. The author who collected the data was not a parent and had not had to make infant feeding decisions. Analysis was conducted by the first two authors. The first author is a mother of two children who were breastfed exclusively for the first 6 months and then breastfed alongside complementary foods for 14 and 18 months respectively. The second author has no children and no personal experience of breastfeeding. The analysts kept a reflexive diary to remain mindful of their own perceptions and experiences of breastfeeding.

Data analysis

Demographic data were used to create pen portraits for each participant (Box 1). Each case was analysed to create idiographic case studies (Eatough and Shaw, 2017) capturing the unique thoughts, experiences, and ideas of each participant. An adapted form of template analysis (Brooks et al, 2014) was used to create a thematic account of each case based on the theory of planned behaviour constructs. A prior theme structure identifying the theory of planned behaviour constructs was used in the first reading, identifying intentions, attitudes, subjective norms and perceived behavioural control. A second reading of each case identified additional factors contributing to feeding intentions. Themes were compared across the sample to produce a thematic narrative. The final themes were developed in an iterative process using constant comparison until the ‘best fit’ for the data was agreed by all authors. Themes are supported by evidence from several participants to ensure trustworthiness (Lincoln and Guba, 1985). The themes, subthemes and definitions for each can be seen in Table 1.

Table 1. Data analysis structure table

| Theme | Definition | Subtheme | Definition |

|---|---|---|---|

| The importance of flexibility | Despite an intention to begin by breastfeeding their child all participants presented themselves as being flexible with this decision | The influence of uncontrollable factors on breastfeeding decisions | While intention to breastfeed was within the mothers' control, a range of uncontrollable factors were perceived to impact on their ability to breastfeed. These included circumstances of the child's birth, the child's preference for how they were fed, the potential challenges that could arise with latching and pain, as well as potential allergies |

| Doing the best for baby | Ensuring the baby was healthy and was the main justification for the need to be flexible with feeding decisions | ||

| Breastfeeding is restrictive | Breastfeeding was portrayed as restrictive for the mother and something that could not be sustained long term. | Desire to get back to normal | Breastfeeding was viewed as restrictive and human-milk substitute portrayed as a means to return to normality |

| Concerns about breastfeeding in public | Participants anticipated a number of negative emotions would result from attempts to breastfeed in public | ||

| Misinformation and unrealistic expectations | A range of attitudinal positions were used for rationalising the transition to human-milk substitute grounded in unrealistic expectations and misinformation | Comparable nutritional value | Human milk and human-milk substitute were presented as having comparable nutritional value |

| Benefits of breastfeeding are time limited | Participants suggested that human milk would only have health and nutritional benefits for the first few days or weeks after birth | ||

| Baby will instinctively know what to do and what they want | There was an assumption that if the child wanted to breastfeed then they would and that this would come naturally with the child capable of choosing their preferred method of feeding |

Ethical considerations

Ethical approval for this research was granted by the Staffordshire University Psychology Ethics Committee on 19 December 2019. All participants provided written informed consent via email. To maintain confidentiality each participant was given a pseudonym and raw data were securely stored, recordings were destroyed following transcription.

Results

All participants were in their 20s, white and with gestation ranging from 24–37 weeks.

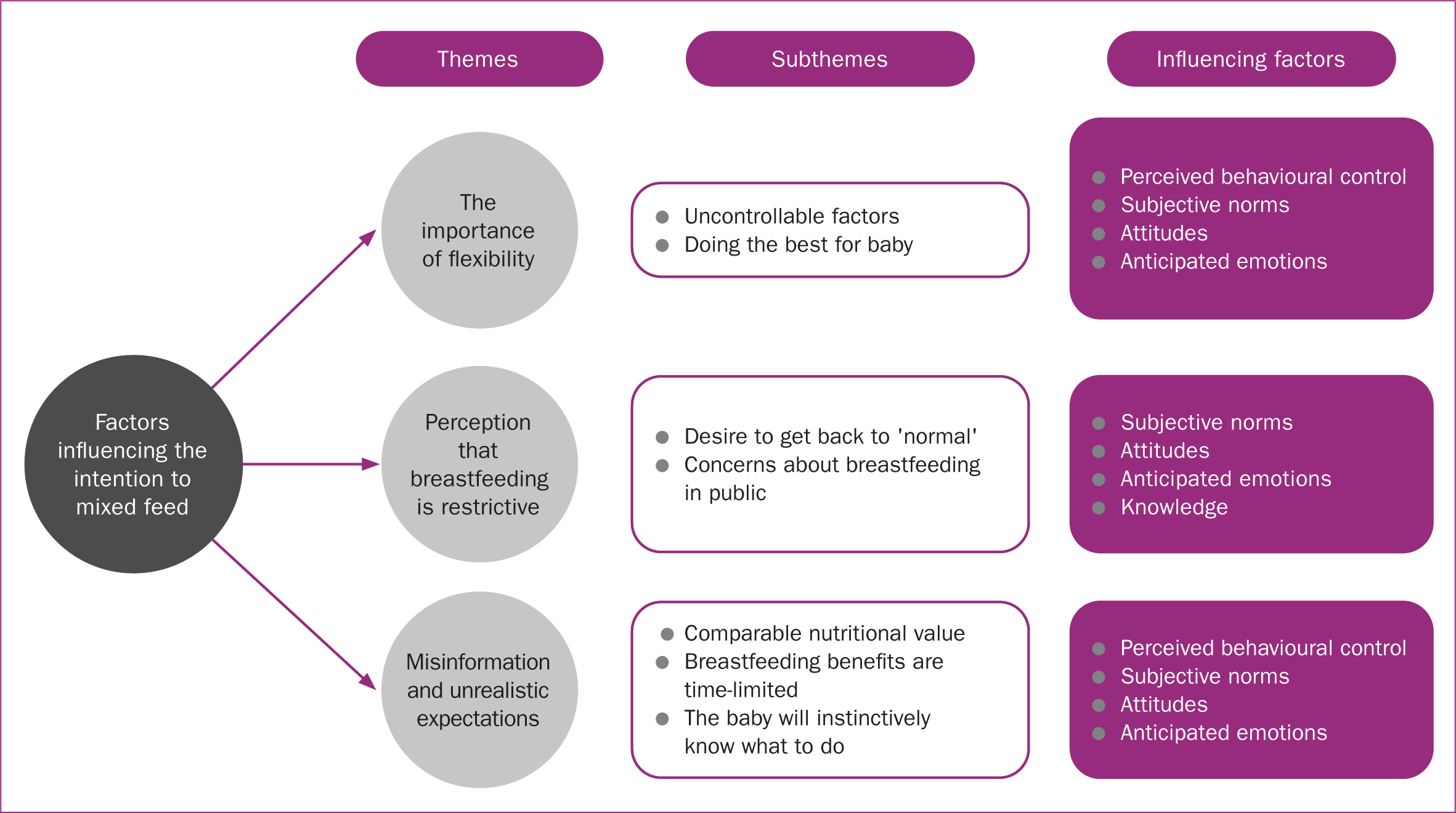

Three main themes underpinned by the theory of planned behaviour constructs were developed. In addition, contributions by two additional constructs not featured in the theory were identified: anticipated emotions and knowledge (see Figure 1).

Figure 1. Diagram of themes, subthemes and influencing theoretical constructs

Figure 1. Diagram of themes, subthemes and influencing theoretical constructs

The importance of flexibility: I'm just going to go with the flow and see how it goes

Despite an intention to begin by breastfeeding their child, all participants presented themselves as being flexible with this decision. This need for flexibility was illustrated within two subthemes, the influence of uncontrollable factors on breastfeeding decisions and the importance of doing the best for baby. Each of these perceptions also served as a form of self-protection in relation to anticipated emotions that could arise if unable to achieve more inflexible breastfeeding goals.

The influence of uncontrollable factors on breastfeeding decisions

While the intention to breastfeed was within the mothers' control, a range of uncontrollable factors were perceived to impact on their ability to breastfeed. These included circumstances of the child's birth, the child's preference for how they were fed, the potential challenges that could arise with latching and pain, as well as potential allergies.

Mixed feeding intentions worked as a form of self-preservation against anticipated emotions relating to guilt and disappointment. For example, Chloe drew upon her knowledge of the emotional impact that not being able to breastfeed had on other mothers, indicating that subjective norms were contributing to a feeling that feeding decisions were out of her control and a need to be flexible.

‘I know some people who are set hearted on breastfeeding and then when the time comes that's not actually possible due to health circumstances…it can be quite disheartening for them.’

(Chloe)

Similarly, Olivia reflected on her own mother's challenges when breastfeeding, highlighting the importance of remaining flexible and the perceived lack of control. Olivia alluded to sources of pressure to breastfeed, with an assumption that these ‘people’ may ask mothers to persevere even when experiencing severe pain. The intention to mixed feed protected Olivia from this pressure and enabled her to make feeding decisions flexibly based on what would be best for her and her child.

‘My mum tried to breastfeed me and…I wouldn't latch properly and when I did she said it was the worst pain ever and that the blood made the milk look like strawberry milkshake…she tried it for three days and she just couldn't do it anymore so I was bottle fed. So I think that…people can be like “oh persevere, persevere” like it will get better…that's a lot when you've just gone through 9 months and then you're having labour and you don't know how things are going to pan out and how you're going to feel.’

(Olivia)

Doing the best for baby

Olivia expressed the attitude that the most important factor was that ‘the baby is healthy’, which was referred to by all participants and worked to justify the importance of being flexible in terms of feeding method.

‘I am flexible, so I do want to breastfeed but if it doesn't work I'm not going to starve my baby. If they won't take to my nipple but they'll have a bottle then obviously I will go with the bottle…My aunt breastfed one [baby] for over a year, then my other aunt had a baby and she didn't breastfeed at all…she was adamant she wasn't going to breastfeed so straight onto bottles, but her babies are fine as well.’

(Olivia)

Alice, extended this attitude by alluding to a ‘fed is best’ narrative, which served to further justify intentions to be flexible, as rigid commitment to breastfeeding could be at the expense of the child not getting the nutrition they needed.

‘I want to breastfeed because I think it is important to have the right method but at the same time…I'm quite flexible. I'm not going to force my child to have breast milk if they doesn't want to. I think the most important thing is that your baby is fed.’

(Alice)

Olivia, Chloe and Lucy also expressed the thought that the nutritional benefits of breastfeeding were time-limited.

Breastfeeding was portrayed as a unique experience. This attitude appeared to be informed partly by subjective norms. For Olivia the experience of her two aunts emphasising that their babies were ‘fine’ regardless of how they were fed served to further validate the acceptability of either feeding method. The importance of flexibility to do what is best for the baby was also emphasised by Lucy, who explained throughout the interview that she knew importance of early breastfeeding both for nutrition and bonding, but also acknowledged that she was likely to switch to an alternative form of feeding after the first 2 months despite this knowledge.

‘For me, breastfeeding would fulfill the bonding aspect of it as well…that is important for me to have, even if it's just for the first month…it's not one size fits all. I'm open to breastfeeding, formula, pumping. I'd be open to trying all of it, so it's important to me that my baby is getting the nutrients it needs but to me, it doesn't matter the method that I use, I'm not fixated, but it's just what's best for my baby.’

(Lucy)

Breastfeeding is restrictive: I don't want to have a baby attached to me for the whole year

The participants did not envisage themselves breastfeeding for any extended period. Their reasons were underpinned by two key perceptions: the belief that breastfeeding was restrictive and that breast milk substitute feeding would enable a quicker return to ‘normality,’ and concerns over breastfeeding in public.

Desire to get back to normal

Breastfeeding was portrayed as restrictive for the mother and something that could not be sustained long term. The value of breast milk substitute to allow others to help was perceived to give the opportunity to spend time away from the baby and establish some ‘normality’. Olivia described breastfeeding as difficult and a struggle that she would need to make sacrifices for and ‘persevere’ with, likely stemming from her perception of her own mother's breastfeeding difficulties.

‘I plan to breastfeed but if it doesn't work and I don't feel like I can carry on persevering and trying then obviously [I'll use] bottle feeding…maybe do a bit of mixed feeding when they're a bit older because I don't want to have a baby attached for me for the whole year…and you can always express and feed from a bottle if you need to pop out if your partner or their mum and dad has them or something like that.’

(Olivia)

Getting back to ‘normal’ was one of the main justifications for using breast milk substitute. Breastfeeding was perceived to be restrictive for both personal life and meeting independently with friends, and there was a perception that breastfeeding would be incompatible with returning to work. This narrative was justified through explaining knowledge that illustrated moving to breast milk substitute would have no detrimental effects. Several of these claims were grounded in misinformation.

‘The reason I don't plan to do it long term is because of the way the baby will depend on me to give it its feeds and stuff like that, because obviously I'll be going back to work anyway, I don't want the baby to only depend on having milk from me, I'd much rather get it into a routine of specific times.’

(Chloe)

Chloe went a step further to stress the risk of isolation and that feeding the baby alone at home could be a threat to mental health if continued long-term. Chloe hinted at anger around a cultural narrative that places the needs of the mother as secondary to those of the infant. Social pressures to breastfeed were at odds with what Chloe viewed as normality. This portrayal of breastfeeding as restrictive and inconvenient while bottle feeding would provide freedom and normality justified the progression to bottle feeding, whenever this might occur.

‘I don't think the health professional and the social media influencers who [say] “ooo it's all for baby”…some people want to have a baby and get back to normal as quickly as possible because… with postnatal depression, you could take into consideration. I feel like just staying at home on your own with a baby can be quite detrimental.’

(Chloe)

Concerns about breastfeeding in public

Anticipated emotions about the discomfort of breastfeeding in public were discussed. This perception was underpinned for Chloe by the assumption that breastfeeding was a barrier to ‘normality’, with it not feeling normal to have people looking at her while feeding in public.

‘I think it's important that you want to live a normal life as possible after having a baby. So you don't want to be thinking “oh that's someone's staring at me”…I just wouldn't feel comfortable getting my boob out in front of everyone on a day out.’

(Chloe)

Lucy was more open to the possibility of feeding in public but still asserted that this may be done ‘hidden’ in her car and repeatedly stated that her initial breastfeeding would take place when she was on maternity leave and at home, hinting that she may be uncomfortable in public.

‘I probably will be at home the first couple of months of my maternity leave. So I think I will breastfeed, because I am very pro-breastfeeding and people doing it in public. Who is to say if I will be comfortable enough in public, but then say I ran to the shop, feeding in the car before I left…I would do that.’

(Lucy)

Olivia also highlighted the perceived acceptability of breastfeeding in public, but only if mothers exercise a certain amount of modesty when doing so. Olivia talked about a sense that some mothers are deliberately exposing themselves when breastfeeding in public. The participants all seemed to be conflicted about their perceptions of whether breastfeeding in public was acceptable.

‘I mean some people…make a point out of it and I see a lot of things on social media where people…[are] not trying to cover up at all. It's not that I don't support it but I don't necessarily agree with it. I wouldn't do it… if you can put a slight blanket over then why wouldn't you?…I definitely want to breastfeed in public, just be more modest about it.’

(Olivia)

Misinformation and unrealistic expectations

The process of breastfeeding was portrayed as natural, simplistic, instant and as providing easy access to milk for the baby. The importance of nutrients, health and building the immune system were also influencing factors in the intention to breastfeed. It was seen as an opportunity to bond with the child in the first few months, with Olivia describing it as ‘a whole new level of closeness’. Despite this acknowledgement, a range of attitudinal positions were used for rationalising the transition to breast milk substitute.

Many of the attitudes that informed the intention to mixed feed stemmed from misinformation and unrealistic expectations, including the belief that the nutritional value of breast milk substitute and breast milk is comparable, that the benefits of breastfeeding are time-limited and that babies instinctively know how to breastfeed and indicate whether they prefer this.

Breast milk substitute and breast milk have comparable nutritional value

Breast milk substitute and breast milk were presented as having comparable nutritional value by Olivia, Lucy and Alice. Olivia explained how formula feeding was ‘just as good’ as breast milk and drew upon the discourse of science to strengthen her comparison, with the implication being that because breast milk substitute is ‘scientifically made’ then it is evidently going to be of high quality. In doing this, Olivia justified her decision to mixed feed and decision to approach the feeding of her baby in a flexible manner.

‘But it's not like if I can't do it, like physically can't do it, then obviously it doesn't matter. Bottled formula will do, it might not be best but it will do the same. It mimics what we have, it will have all the vitamins and stuff in them in it needs… it's scientifically made, the formula, so if you can't breastfeed then I don't really think they are going to be losing out on a lot, so it's not really something I'm worried about.’

(Olivia)

Benefits of breastfeeding are time limited

For Olivia, Chloe and Lucy the benefits of breastfeeding were constructed as largely time limited. By breastfeeding early on, they would be doing the best for their baby. This was the time when nutrients were needed to build the immune system and it was important to establish a bond. As the child got older, the transition to breast milk substitute would be just as good for their child as continuing to breastfeed. Chloe alluded to the need for flexibility by comparing her own perspective to that of mothers who had more inflexible breastfeeding intentions. Chloe also stressed the importance of knowledge and the role this played in her initial aim to breastfeed for the first few months. Her account also illustrated some uncertainty, with the suggestion that with ‘more information’, Chloe's intention may be different, and she may intend to breastfeed beyond her initial goals.

‘There are a lot of people that are completely full breastfeeding and it's the only thing that they'll stick by…so maybe if I had a bit more information then I'd probably try it for longer but obviously because I've heard about the fact that the first feed is most important, I feel that's persuaded me to do it for the first two or three months.’

(Chloe)

The baby will instinctively know what to do and what they want

There was an assumption that if the child wanted to breastfeed then they would, and that this would come naturally. Olivia reinforced this view of breastfeeding as natural by drawing comparisons with animal instincts to feed after birth. Olivia's account illustrated an attitude that breastfeeding is the natural way to feed.

‘I just want to try breastfeeding because it's the most natural way…its natural, we've all done that, animals do it, it's just how it is. It's our own source, so why not use it?’

(Olivia)

For Alice, it was also important to consider whether both herself and the baby would like breastfeeding, indicating an assumption that the newborn may be able to consciously form a preference for the bottle and reject her breast. Alice's account also highlighted a unique consideration about whether she would enjoy breastfeeding herself. Alice acknowledged that breastfeeding is not all about the child, but consideration of the mother's comfort is also an important factor.

‘You can't predict the future…I don't know what my baby's going to like, I don't know what I'm going to like…if I don't like breastfeeding [and] my baby likes it, I think that's another decision…I think I would end up stopping because…as much as you know my baby is important…but I am as well. You've got to be happy with what's going on because then your baby will be happy as well.’

(Alice)

Discussion

In this study, the factors contributing to pregnant women's intentions to mixed-feed their baby after birth and the contribution of the theory of planned behaviour (Ajzen, 1991) to these intentions were explored.

The importance of remaining flexible in feeding decisions was justified by the participants in relation to protection from anticipated emotions. These concerns were not unfounded; those who intend to breastfeed but are unable to meet their goals are at heightened risk of guilt, frustration and anger (Brown, 2018). These emotions may stem from internalised shame, with implications for help seeking and a mother's mental health (Thomson et al, 2015). This fear of negative emotions indicates a problematic culture in which mothers are shamed if they do and shamed if they do not breastfeed (Thomson et al, 2015). The model of goal-directed behaviour (Perugini and Bagozzi, 2001) has been shown to explain additional variance to the theory of planned behaviour for diet and exercise, and proposes that anticipated emotions relating to the appraisal of goal achievement play a role in the development of desires to engage in behaviours. This requires further exploration in the prediction of infant feeding intentions.

The anticipation of negative emotions from not meeting strict breastfeeding goals may also be influenced by infant feeding knowledge. Breastfeeding knowledge has been shown to be the strongest predictor of exclusive breastfeeding, followed by the theory of planned behaviour variables (Zhang et al, 2018). All participants rationalised mixed feeding using some form of misinformation or unrealistic expectation about breastfeeding. The correction of infant feeding misconceptions and enhancement of breastfeeding knowledge is therefore an essential first step towards increasing breastfeeding rates.

In the UK, the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE, 2006; 2008) guidelines advocate for breastfeeding information to be provided by healthcare professionals during antenatal and postnatal care. However, vicarious experiences and personal relationships were valued above healthcare professional advice in this sample. The perception of other people's views on feeding methods has been illustrated to be an important determinant of the initiation and continuation of breastfeeding, particularly views of partners (Swanson and Power, 2005; Yang et al, 2018) and own mothers (Swanson and Power, 2005). The current NICE focus on the provision of information by healthcare professionals alone may not effectively inform women about breastfeeding benefits. Guidelines should include more consideration of how peer supporters and family networks can be involved in enhancing breastfeeding knowledge and the provision of support.

Perceptions of the time-limited benefits of breastfeeding highlight that mothers are aware of the value of colostrum. These initial feeds can help to boost the child's immune system (Andreas et al, 2015), However, it is longer term breastfeeding that will have the greatest benefits for both mother and child (Brown, 2019a). It is concerning that mothers use this knowledge as a rationale for introducing breast milk substitute against WHO (2020) recommendations and illustrates that the methods by which knowledge is conveyed and understood requires further investigation. This time-limited value was also stressed by the participants as a justification for progression to breast milk substitute, to get ‘back to normal’ in their lives postpartum. This vision of normality may be explained by vicarious experience of breast milk substitute feeding that has been shown to influence the behaviour of first-time mothers resulting in a decreased likelihood of breastfeeding (Bartle and Harvey, 2017). Portraying breastfeeding as a restrictive inconvenience and bottle feeding as a return to ‘normality’ has important implications for women's intentions for how they will feed their baby and is routed in bottle feeding culture.

Bottle feeding culture also explains the anxiety expressed by the participants around breastfeeding in public. The invisibility of breastfeeding means that when problems with pain, latch or supply are encountered, the lack of support options results in mothers who may perceive their bodies as ‘failing’ (Brown, 2019b) and have a significantly increased risk of postnatal depression (Brown et al, 2016), which can occur when breastfeeding expectations do not align with experiences (Borra et al, 2014). Fears are likely to be grounded in a cultural narrative that includes medial portrayals of breastfeeding in public as exhibitionist and breastfeeding at home as the most appropriate way to feed an infant (Grant, 2016). This illustrates a need to challenge these cultural narratives to enable more women to feel comfortable and confident about the choice to breastfeed their infant whenever and wherever they need to.

The flexibility of mixed feeding may also be protective from negative mental health impacts for the small proportion of women physically unable to breastfeed. It would be valuable to explore the function of these perceptions and whether these views are protective in terms of mental health for mothers with the intention to mixed feed who are later unable to breastfeed. Arguments for breast milk or breast milk substitute feeding were primarily related to nutrition and this may explain the potentially protective nature of intent to mixed feed, as those women who intend to exclusively breastfeed are often doing so for a broader range of reasons than nutrition alone. Therefore, the psychological impact of not meeting these goals could weigh more heavily (Brown, 2019b).

Breastfeeding was portrayed as a natural endeavour that the child would be able to do with little support. Some of the participants drew comparisons with animal instincts to feed after birth. However, this discourse of breastfeeding being ‘easy’ and ‘natural’ and assuming that the baby will simply know what to do, just as a baby animal would, is a potentially dangerous assumption. It overlooks the need for realistic guidance and support to help women feel empowered to overcome breastfeeding challenges and to continue breastfeeding, rather than assuming breastfeeding is not going to work and moving to breast milk substitute if a challenge is encountered.

Challenges with breastfeeding were assumed to reflect a child's preference against breastfeeding, and this was used as a rationale for the need to be flexible. This performed a protective role enabling avoidance of negative emotions associated with not meeting breastfeeding goals that may not fit with their child's preference. This assumption may mean these mothers intending to mixed feed are less likely to educate themselves around breastfeeding challenges and as a result be less prepared to seek support. There is evidence to suggest that women with unrealistic expectations about breastfeeding are more likely to wean early (Hegney et al, 2008). This may help to explain why women who choose to mixed feed are more likely to cease breastfeeding by 9 weeks postpartum (DiGirolamo et al, 2005).

Limitations

To enhance trustworthiness of the results, the author who collected the data and those who analysed it took a reflexive approach and were thorough and transparent in the methods used. However, this was a self-selecting sample and all participants were young, white, first-time mothers. More research is needed with broader populations and the current findings should not be applied across cultures. Long-term experiences exploring whether actual behaviour was in line with intentions should also be explored.

Conclusions

Feeding intentions contribute to feeding behaviours, but there are various factors that bear influence. Women need access to accurate and clear information and to be informed and supported by professionals, peers, families, and broader communities. Cultural narratives must be challenged to enable mothers to feel in control of feeding decisions and without the need to justify feeding activities to protect themselves from anticipated negative emotions.

Key points

- Although a mother's intention to mixed feed their child is associated with reduced breastfeeding duration, little research has specifically explored women's intention to mixed feed.

- Women's intentions to mixed feed were driven by their beliefs around the importance of feeding flexibility, the perception of breastfeeding as restrictive and the presence of misinformation and unrealistic expectations.

- The findings develop psychological theory through the confirmation of the value of the theory of planned behaviour constructs for understanding mixed feeding intentions. In addition, the work makes a unique contribution through the identification of two additional contributing constructs: anticipated emotions and knowledge.

CPD reflective questions

- How would you support a mother to make an informed decision about feeding her baby?

- What support could you provide to a mother who was uncertain about her feeding intentions?

- How can you encourage flexibility in thinking around a mother's feeding intentions?

- How might guilt and pressure play a part in determining whether or not a mother breastfeeds?