The wellbeing of health professionals can be linked with the quality and safety of healthcare services (Hall et al, 2016; Royal College of Physicians, 2016). Midwives in particular can experience a range of work-related psychological distress and are more likely than other health professionals to report feeling pressured at work (Pezaro et al, 2015; National Maternity Review, 2016). The significance of this issue has been recognised, as workforce research is now listed as one of the most prominent global research priorities for the international midwifery community (Soltani et al, 2016).

In light of this, any work-related psychological distress that may be affecting the quality and safety of maternity care must be explored and addressed. Psychological distress can be defined as a unique, discomforting, emotional state experienced by an individual in response to a specific stressor or demand, which results in harm, either temporary or permanent, to the person (Ridner, 2004). In the case of defining work-related psychological distress, we propose that the ‘specific stressor’ would therefore need to be work-related. A recent report from the National Childbirth Trust (NCT) has explored women's experiences of maternity services and recommended that staff burnout be prevented and addressed (Plotkin, 2017). However, women's experiences of work-related psychological distress in midwifery populations specifically has yet to be explored as a research problem in need of an evidence-based solution.

Patient and public involvement

It has been well established that co-designing research with patients and the public benefits the project, the service user and the organisations involved (Steen et al, 2011; Bradwell and Marr, 2017). This is because the patient is the key stakeholder in their own care, and their contribution to the quality and safety of services in research is widely recognised (Vincent and Coulter, 2002). Patient and public involvement (PPI) can provide a qualitative description of context, experiential knowledge and insightful contributions to the research agenda (Boote et al, 2002; Staley, 2015).

Traditionally, the involvement of patients and the public in research has been reported inconsistently within the literature (Mockford et al, 2012; Brett et al, 2014). It has been suggested that such poor reporting can result in a weaker understanding of the evidence base, making it more challenging to implement the findings of studies in terms of best PPI practice (Brett et al, 2017). Consequently, new Guidance for Reporting Involvement of Patients and the Public (GRIPP2) reporting checklists for PPI in research have been developed to enhance the quality, transparency, and consistency of the PPI evidence base (Staniszewska et al, 2017). This has resulted in more recent publications using GRIPP2 reporting checklists to report how their PPI activities have contributed to the design of new research in healthcare more consistently and accurately (Andrews et al, 2015; Morgan et al, 2016).

Similarly, this article uses the long GRIPP2 reporting checklist to report how PPI activities have been used to co-design a research proposal with new mothers as members of a project steering group. We used the definition of PPI as proposed by INVOLVE:

‘Research carried out “with” or “by” members of the public rather than “to”, “about” or “for” them’

In line with Steen et al (2011), we defined co-design as ‘creative cooperation during the process of designing research’—in this case a research proposal. The research proposal in question outlined plans to develop and evaluate an online intervention to primarily support midwives experiencing work-related psychological distress (Pezaro, 2016). The complete evidence and theory-based design of this intervention drew on the revised transactional model of occupational stress and coping presented by Goh et al (2010), and has been published in full elsewhere (Pezaro, 2018). The aim of this research proposal, guided by the Medical Research Council's framework for developing and evaluating complex interventions (Craig et al, 2008), is to address the research problem of work-related psychological distress in midwifery populations. PPI activities therefore also looked to explore the perspectives of new mothers in relation to this topic. To the authors' knowledge, this is the first publication to report these unique areas of enquiry concomitantly.

Principally, this PPI was instigated in light of the fact that the voices of new mothers have yet to be explored or incorporated into such future research planning. Consequently, the aims of this PPI were:

In order to meet these aims, the PPI questions associated with these activities were:

Methods

Design

These PPI activities took a co-design approach, focusing on qualitative data to explore new mothers' perceptions of barriers to receiving high-quality maternity care, the psychological wellbeing of midwifery populations and a research proposal outlining the development and evaluation of an online intervention to support midwives in work-related psychological distress. The GRIPP2 long form was used to support the reporting of this work (Staniszewska et al, 2017). In line with recommendations, PPI activities were conducted at the earliest conceptual phases of developing a research proposal before submitting a funding application, as a preliminary activity to inform the direction of planned future research (INVOLVE and NIHR, 2012; Buck et al, 2014). Ethical approval was obtained for this PPI work before it took place.

Participants

New mothers, including pregnant women with experience of using the maternity services in the UK within the 12 months before this PPI, were eligible to participate. In this case, non-English-speaking mothers were excluded from participation. A self-selecting sample was recruited via Twitter, academic blogs, ‘The academic midwife’ Facebook page, and mother and baby groups. Participants received refreshments and £20 for their time.

Procedure

All PPI activities were undertaken during a 2-hour face-to-face discussion group in a local community centre and were led by the first author. Firstly, the role of PPI was introduced, and participants were invited to become members of the project steering group, should the research proposal be successful in securing research funding. Subsequently, all provided their informed consent to participate in the data collection aspect of this PPI session. This informed consent was required to share the voices of these new mothers more widely through publication.

Next, participants were then introduced to and asked to reflect on a lay summary of proposed research, which outlined the development and evaluation of an online intervention designed to support midwives in work-related psychological distress, as is standard in PPI (Morgan et al, 2016). A background to the proposed research was also provided, to place the proposal in context with the phenomenon under study. Participants were then invited to complete a feedback form. This feedback form prompted written responses in relation to the appearance and significance of psychological distress in midwifery populations; the potential consequences of work-related psychological distress in maternity services; the value of psychological support in the maternity workplace; and the development and evaluation of a confidential, anonymous online intervention to support midwives in work-related psychological distress. Participants were also invited to write down their reflections as discussions evolved. These methods were chosen as free-writing can enable participants to consider new meanings and internal dialogues reflexively in relation to the topic under discussion (Elizabeth, 2008). Discussions were digitally recorded and transcribed verbatim. Field notes were also taken throughout.

At the end of this PPI session, the first author recapped the perspectives expressed by participants, in order to clarify the accuracy of interpretation. This permitted participants to revise and clarify any contributions made. The names of any individual midwives and/or maternity services were omitted from the analysis of results.

Data analysis

All qualitative data were analysed together in Microsoft Excel software using the five-stage framework analysis (Ward et al, 2013). This type of analysis was chosen as it is a deductive form of thematic analysis designed to answer PPI questions pragmatically. All data and generated themes were given equal weighting.

The final framework was developed by identifying recurrent and important themes that corresponded with new mothers' perceptions of maternity services, the phenomenon of work-related psychological distress in midwifery populations, and the proposed research plan to support them via an online intervention. To enhance the rigour and trustworthiness, the process of developing and refining these themes was peer reviewed by co-authors (Fernald and Duclos, 2005). Furthermore, a reflexive process of writing, peer review and discussion was employed throughout (Greene, 2014).

New mothers saw poor workplace practices, poor communication, service constraints and inconsistencies as barriers to them receiving high-quality care

Findings

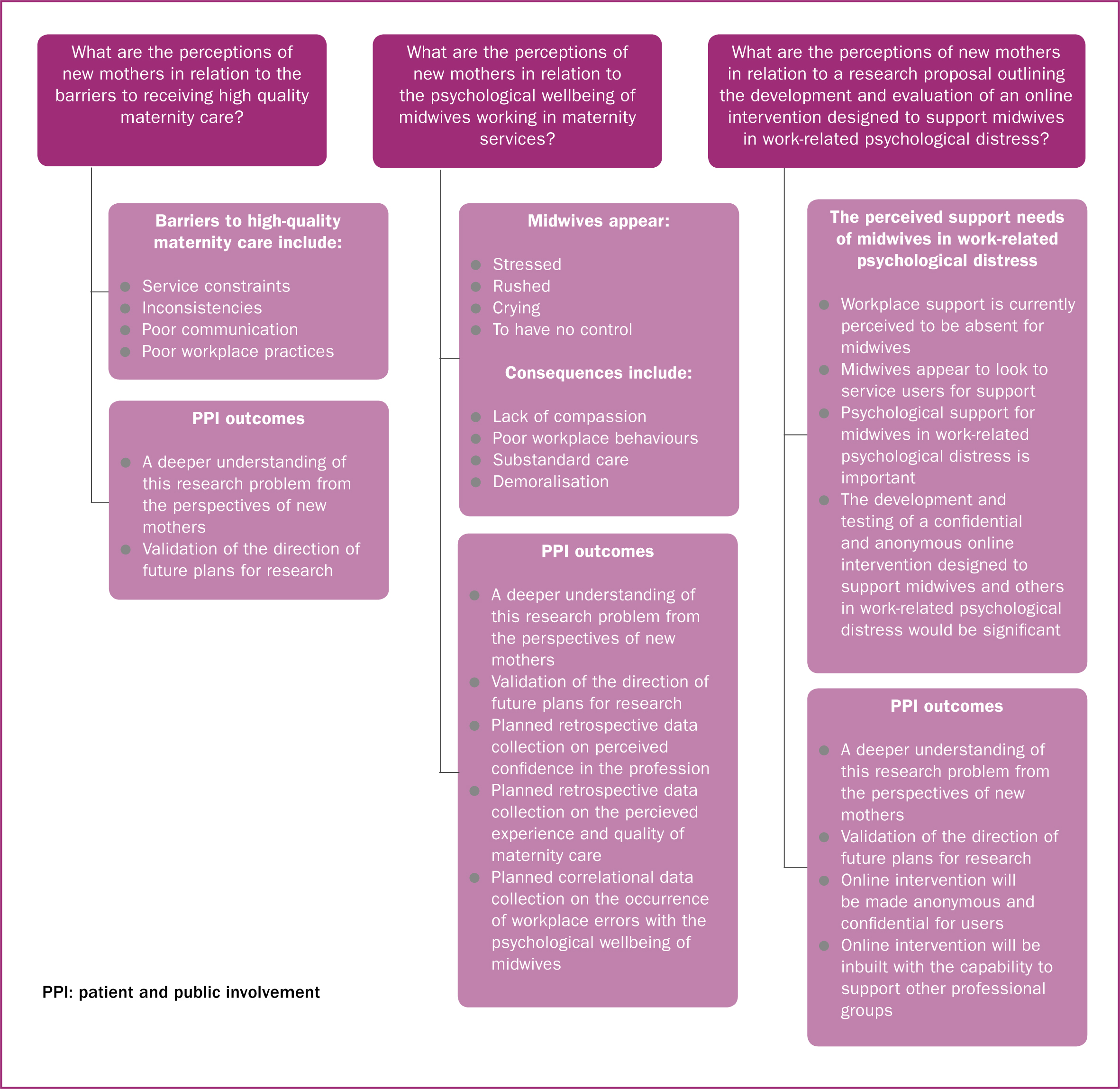

A total of 10 new mothers who met the inclusion criteria were recruited for this PPI. No demographic information was requested as these were PPI activities; however, some participants disclosed that they had received a variety of antenatal, intrapartum and postnatal care from maternity services based within the London, South East and East Midlands areas of England. Figure 1 provides an overview of all results.

Four themes and 16 subthemes were identified regarding the perceptions of new mothers, in line with the framework analysis approach (Ward et al, 2013). Theme one summarises new mothers' perceptions of barriers to receiving high-quality care in maternity services; theme two presents new mothers' perceptions in relation to the psychological wellbeing of midwives working in English maternity services; theme three collates the perceived consequences of work-related psychological distress in midwifery populations; and theme four reports on the support needs of midwives in work-related psychological distress from the perspective of new mothers. In line with best practice, these results are reported in a way which maximises the number of voices heard (NIHR, 2015; Moss et al, 2017).

In summary, these new mothers saw poor workplace practices, poor communication, and service constraints and inconsistencies as barriers to them receiving high-quality care. They also observed that midwives appeared stressed and rushed on occasion, and seemed to have no control. Three participants had also seen midwives cry or become emotional. These new mothers perceived the consequences of work-related psychological distress in midwifery populations to be a lack of compassion, poor workplace behaviours, substandard care and demoralisation. Furthermore, midwives appeared to look to service users for support in some cases, as there was a perceived lack of staff support in place. Nevertheless, this group of new mothers believed that psychological support was important for midwives in the workplace, and that the development of a confidential and anonymous online intervention to support midwives in work-related psychological distress would be significant.

Perceived barriers to receiving high quality care in maternity services

Participants reflected on their experiences with maternity services, and began to share what they perceived to be barriers to receiving high-quality maternity care. These barriers included service constraints, inconsistency, poor communication and poor workplace practices.

‘Midwives are not able to do the job they want to do’

Here, participants largely reflected on their experience of staff shortages, and how this made it more challenging for midwives to provide high quality care. While it was recognised that midwives wanted to deliver high quality care, the working nature of maternity services made this seemingly impossible to achieve.

‘Midwives are clearly overworked, there is a huge shortage of them in hospitals leading to units being closed for short periods of time.’ (Feedback form)

‘I never felt that the midwives involved were to blame and felt bad for them at the time as they were clearly too busy to do what they needed for each patient, but the lack of staffing/resources was very apparent, and I do feel it affected my care and outcome in very significant ways.’ (Written contribution)

‘I had no consistency’

Opposing experiences in maternity care were described throughout the maternity services. Some new mothers also reported a lack of continuity in both their carer and maternity care. It was also suggested that midwives seemed less ‘stressed’ while working away from the labour ward setting.

‘I had no consistency, I saw a different face every time.’

‘Midwives share their own opinion—there is no collective voice.’

‘I never knew her name’

Poor communication was recognised by these participants as a barrier to high-quality maternity care, and was reported to occur between staff, and between staff and service users.

‘It seems to be that there is a lack of sharing best practice; getting together as midwives collectively and speaking about different approaches, research, new understandings, new techniques—just what works … just seems that everyone is working in their own little silos … especially the community midwives.’

‘I did note a lack of communication.’ (Feedback form)

‘There is poor management’

Some participants reported that midwives seemed to be poorly managed. There was also seemingly a lack of teamwork. For these new mothers, such poor workplace practices were perceived to obstruct the delivery of high-quality care.

‘I did note a lack of comradery [sic] between areas.’ (Feedback form)

‘More support across the teams needed.’ (Written participant contribution)

New mothers' perceptions of the psychological wellbeing of midwives in maternity services

While reflecting on midwives' psychological wellbeing in the maternity workplace, participants began to report a variety of incidents where midwives openly appeared to experience work-related psychological distress. Participants often described this as the midwife seeming ‘stressed’ or ‘rushed’, yet some also alleged that midwives were seen to ‘keep calm and carry on’. Midwives were also sometimes seen to appear crying, or to have no control. Only a minority of data analysed from qualitative survey responses reported that some individual midwives did not appear to experience any work-related psychological distress at all.

‘The midwife was clearly stressed’

Participants described how midwives appeared to be ‘stressed’ while caring for them; however, some new mothers expressed how midwives carried on caring for them regardless.

‘They hid it well—occasionally cracked.’ (Feedback form)

‘The midwife was clearly stressed.’

‘The midwife always seemed to be rushing’

Here, participants described midwives appearing to be ‘rushed’. This was often described as midwives ‘cramming’ in work rather than being able to spend adequate time providing quality maternity care.

‘She didn't have enough time, she didn't have enough to go through things properly, it was all a bit rushed and a bit sort of whizzed through.’

‘The midwife always seemed to be rushing between places and didn't really know who was supposed to be coming.’

‘Midwives cry’

Within this subtheme, midwives were seen crying or becoming emotional in the workplace. These displays of emotion were attributed to various experiences of work-related psychological distress.

‘Midwives can get emotional due to stress.’ (Researcher notes taken from discussion)

‘She said … “labour ward is closed, there is not enough staff … I am with a woman who is 6cm and I can't leave her for more than a couple of minutes”… and then she got emotional.’

‘No one was in control’

Not only did participants express that at times, midwives appeared to have no control over clinical situations in maternity services, they also perceived midwives to have no control over some of the decisions taken in the maternity workplace.

‘She just lost control of the situation.’

‘In my labour experience, the midwife was under lots of stress from the workload, other midwives and how the situation was developing. This led to her losing control of the situation.’ (Feedback form)

Perceived consequences of work-related psychological distress in midwifery populations

While exploring their own insights in relation to midwives' psychological wellbeing, participants reflected on what they perceived to be the consequences of work-related psychological distress in midwifery populations. Here, participants largely referred to a perceived lack of compassion, poor workplace behaviours, substandard care and demoralisation within the maternity services.

‘My midwife was not sympathetic’

Participants described how midwives displayed a lack of compassion towards both service users and each other. From the perspective of new mothers, these displays of compassion fatigue were regarded as a consequence of work-related psychological distress.

‘The midwife was clearly stressed, she was really impatient with me.’

‘Stressed midwife was quite impatient and mean.’ (Feedback form)

‘There is a lack of kindness shown between staff’

Here, participants described how they had witnessed incivilities between midwifery staff, including undermining and bullying behaviours. Some midwives were also seen to openly blame others and behave competitively in the workplace. There was also a lack of kindness noted between midwifery staff.

‘They both spent a lot of time visiting me … telling me how they do it better than the other midwife.’

‘I can see the senior midwives coming in to perform the procedures which she was failing to do, rolling their eyes.’

‘Midwives were making mistakes due to stress’

Both specific and non specific episodes of substandard care were observed by participants. Here, work-related psychological distress was linked to increased levels of pain and delays in pain medications. Mistakes were also attributed to high levels of work-related psychological distress. Specific mistakes included medication errors and breeches in confidentiality.

‘She wasn't keeping up with checking the baby's heart rate, which had been made clear in front of us by a senior midwife.’ (Feedback form)

‘Forgetting basic things e.g. tea and medication.’ (Written participant contribution)

‘…Instantly makes you lose confidence.’

Here, participants described how midwives appeared to be unsupported by others within their profession. Moreover, participants also described how they began to lose faith in the midwife providing their care, if the midwife appeared to be experiencing work-related psychological distress.

‘Inexperienced midwives have no support—lose confidence—they need their hands holding.’ (Participant notes from discussion)

‘This led [to] me not trusting her again.’ (Feedback form)

The perceived support needs of midwives experiencing work-related psychological distress

Participants reported how support seemed to be absent for midwives in the workplace. In some cases, participants also described how midwives experiencing work-related psychological stress appeared to seek support from service users. Participants also reflected on the importance of psychological support and the significance of an online intervention designed to support midwives in work-related psychological distress.

‘There is clearly nowhere for midwives to go’

It was evident to some participants that midwives did not have access to psychological support in the workplace. Participants expressed both concern that there was seemingly nowhere for midwives to seek help safely, and that the provision of any structured support for midwives was seemingly absent.

‘There clearly wasn't anyone for her to go to comfortably.’

‘She didn't have any support from anyone.’

‘Midwife shared she was struggling’

In some cases, midwives appeared to seek psychological support from those in their care. Some participants reported how this involved the midwife openly complaining of work-related psychological distress. Others reported how midwives actively sought comfort from them during the course of their maternity care.

‘They need to be supported from within; they can't be reliant on the birthing mothers to hold their hands and pat them on the back.’

‘The midwife let me know how stressed she was.’ (Written participant response)

‘It is important that we support their mental and physical health as much as they support ours’

Participants highlighted unanimously how important support would be for midwives experiencing work-related psychological distress. Participants also noted how such support could be expanded to care for a range of health professionals. There was also recognition of how the quality of maternity care may have been improved had midwives been having a ‘good day’ in the workplace.

‘If she was having a good day I would have felt calmer in the situation and probably wouldn't have needed an epidural.’ (Feedback form)

‘NHS workers have such important job and can be very emotionally taxing.’ (Feedback form)

‘Midwives should be able to gain help without their workplace knowing.’

Having reviewed a lay summary of proposed research to develop and evaluate an online intervention to support midwives in work-related psychological distress, the group was keen to see this research progress. While some participants noted that they themselves might prefer to seek face-to-face support, they also recognised that midwives might need access to flexible, anonymous and confidential support online. Overall, the proposed development and evaluation of the online intervention was unanimously endorsed by this group of new mothers.

‘PTSD [post-traumatic stress disorder] must affect a lot of midwives.’ (Feedback form)

‘Hours could make it difficult to seek counselling but can access online support at all times.’ (Feedback form)

PPI outcomes

The findings of these PPI activities have led to seven outcomes. Firstly, these findings provide a deeper understanding of this problem from the perspectives of new mothers, validating the direction of research. Additionally, as this group of new mothers linked the appearance of work-related psychological distress in midwifery populations with reduced confidence in the midwife, ongoing research will now plan to assess any future changes in these perceptions through post-intervention qualitative research. Similarly, as some participants linked the appearance of work-related psychological distress in midwifery populations with reduced quality of care and poorer experiences, future research will also now reassess these perceptions in a post-intervention study.

Furthermore, this group of new mothers attributed a range of mistakes to the appearance of work-related psychological distress in midwifery populations. Consequently, ongoing research will now correlate workplace errors with midwives' psychological wellbeing. This group of new mothers also endorsed the provision of anonymity and confidentiality for users of the proposed online intervention, and so this will be incorporated into prototypes of the intervention. Lastly, future prototypes of the intervention will also be built with the capability to support other professional groups, as participants suggested that this may be useful for future evaluations, implementation and distribution.

Discussion

The overarching aims of these PPI activities were met by examining new mothers' perspectives of work-related psychological distress in maternity services, and the development and evaluation of an online intervention designed to support midwives. This PPI also established that work-related psychological distress in midwifery populations could negatively affect new mothers' experiences of maternity care. In relation to the research plan shared with this group of new mothers, participants gave their full support to the proposal, and recognised the need for midwives to have access to flexible, anonymous and confidential support online. These particular findings mirror other research, where workers described how flexible, anonymous, online mental health support in the workplace would facilitate increased rates of engagement (Carolan and De Visser, 2018).

While the research team were aware of some of the more sensitive issues raised in our findings beforehand, understanding has been expanded by some inimitable findings, particularly in relation to trust and confidence in the midwifery profession. As well as addressing the three PPI questions presented here, the findings also led to seven PPI outcomes, which established a clear contribution to a larger research project. These more specifically related to the particulars of intervention development and new long-term plans for retrospective data collection. These outcomes in relation to data collection particularly exceeded initial expectations and brought new insights to the research team who can now plan beyond the scope of the original research proposed.

The findings of this PPI corroborate previous research that has established that midwives can sometimes attempt to mask the negative effects of work-related psychological distress (Pezaro et al, 2016). However, a unique finding of this work was that midwives could also sometimes seek support from service users. Here, findings echoed those of other studies, where the consequences of work-related psychological distress were also found to include a lack of compassion (Sorenson et al, 2016), poor workplace behaviours (Lombardo and Eyre, 2011), reduced quality of care (Krämer et al, 2016) and workplace errors (Hall et al, 2016). These findings also reflect those in Better Births (National Maternity Review, 2016), which also established links between poor teamwork, poor professional cultures, poor communication, inconsistency, low morale, poor management, a lack of support and poor maternity care. Following on from Better Births, a new A-EQUIP model of supervision will incorporate restorative clinical supervision for midwives in the workplace (Petit and Stephen, 2015), although the effect of the model is yet to be evaluated.

Influences on future studies

The broader qualitative findings presented here offer a strong rationale for the development and evaluation of the proposed intervention, given the effect that work-related psychological distress seemingly has on the quality of maternity care. This impact is demonstrated by one particular instance where a participant suggests that she ‘probably wouldn't have needed an epidural’ had her midwife been having a good day. As such, future research could usefully explore the depth of this relationship between the quality of maternity care and the psychological wellbeing of midwives.

While studies have highlighted staff shortages (Palmer and Brackwell, 2014), the paucity of evidence-based support available to midwives (Pezaro et al, 2017) and the reality of work-related psychological distress in midwifery populations (Coldridge and Davies 2017), this PPI explored how new mothers perceived the these issues when receiving maternity care. Findings demonstrated that new mothers would be supportive of a confidential and anonymous online intervention to support midwives in work-related psychological distress. This is particularly interesting to note, as previous research has highlighted how some professionals may be reluctant to allow the inevitable amnesty which anonymity and confidentiality would permit for midwives seeking support (Pezaro and Clyne, 2016). As such, there is now an opportunity to develop, test and evaluate a confidential, anonymous, evidence-based online intervention to support midwives experiencing work-related psychological distress in line with proposed research plans, and with the validation of maternity service users.

Research considerations

As this PPI was qualitative in nature, the research team initially considered employing the Consolidated Criteria for Reporting Qualitative Research (COREQ) (Tong et al, 2007). However, the needs, aims and scope of PPI are not the same as for qualitative research alone. For researchers, there is also a dichotomy between simply describing the perceptions of a PPI group within a larger study and publishing these as standalone findings that add new and valuable knowledge to the field. However, it is important to share PPI activity in order to comprehend ‘how it works’ (Staley, 2015), and to appreciate the contributions of PPI groups, in order to understand what value they add in shaping future research. In this case, the valuable perceptions of new mothers have been used to inform future research planning and the development of a confidential and anonymous online intervention for midwives, to be evaluated via an initial feasibility study and potentially, a future adequately powered trial. Crucially, this PPI has also been reported so as to maximise the number of perspectives heard.

PPI was particularly valuable to this research, as it enlightened the research team to the profundity of the problem from service users' perspectives. As such, these insights can now be embedded throughout the entire future research programme. Overall, the amelioration of work-related psychological distress in midwifery populations is perceived to be required by this group of new mothers for the benefit of midwives, maternity care and maternity services. Both national and international strategies and frameworks relating to healthcare services tend to focus on putting the care and safety of patients first (Mallari et al, 2016), yet these findings suggest that to deliver the best care to new mothers effectively, the care of the midwife must equally be prioritised. Future research could also usefully replicate this PPI as a qualitative study with mothers from other countries and across a range of healthcare settings to assess the transferability of these findings.

Strengths and limitations

Overall, the aim to include the perspectives of new mothers in future research worked well and was carried out in accordance with the principles of successful PPI involvement in NHS research (Boote et al, 2006). The involvement of new mothers in the development of this research proposal was useful and meaningful. Therefore, as guided by the long GRIPP2 checklist (Staniszewska et al, 2017), the definition of PPI used here was deemed to be appropriate, without the need for any changes. However, in inviting new mothers to contribute, the researcher was challenged with trying to engage participants in meaningful and uninterrupted conversations with infants present. As such, noise levels compromised some audio recordings, leading the researcher to rely on field notes taken during the group discussion at times.

At this early stage of planning future research, this PPI group may have benefitted from more comprehensive research training to support their decision-making processes in this context. PPI in this case concerned the voice of new mothers being heard in relation to a unique research problem. This has meant that new research plans will be shaped in line with new mothers' priorities. Additionally, this PPI also means that the research, midwifery and healthcare communities are now better placed to improve maternity services in relation to the perspectives of new mothers.

Two authors (SP and EB) are registered academic midwives. GP is a British Psychology Society Chartered Psychologist, methodologist, and a researcher in co-creation and patient involvement. In using their multidisciplinary backgrounds, the authors were able to strengthen the academic discussions in this work; however, potential biases may have arisen from personal experiences of psychological distress in the midwifery workplace and a desire to pursue this line of research.

While this PPI has provided unique insights into the perspectives of new mothers, it was limited by the recruitment of a small homogenous sample, from which it is challenging to draw generalisable conclusions. Participants were encouraged to discuss the phenomenon under study to answer precise questions, where they may not otherwise have done so. However, a key strength of this PPI is that it has been able to give a voice to new mothers and include this in future research. These voices have also given the research team a far greater understanding of the phenomenon under study. This may be a far more significant problem for maternity services than initially thought, considering some of the findings, such as midwives seeking solace in service users. Such discoveries may not have been realised had midwives or potential users of the proposed online intervention been invited to join in PPI activities instead.

There is an important distinction to be made between the perspectives of the public and the perspectives of health and social care professionals (INVOLVE and NIHR, 2012). As midwives are not considered to be patients under this guidance, they were not included in these particular PPI activities. Yet while it may be new mothers who may benefit from a better supported workforce, it is midwives who could directly gain from increased support. Arguably therefore, health professionals should not necessarily be excluded from PPI activities simply because they treat patients, especially when they are the direct beneficiary of an intervention. In developing an online intervention to support midwives experiencing work-related psychological distress, the midwife could also usefully be considered to be either a patient or a member of the public, in line with more recent guidance (Greenhalgh, 2017). Nevertheless, this dichotomy lends itself to further academic discussion.

Conclusion

These are the first PPI activities to explore new mothers' perspectives of the barriers to high-quality maternity care, the psychological wellbeing of midwives, and the provision and evaluation of online support for midwives experiencing work-related psychological distress, concomitantly. New mothers were given a voice to ensure that their perspectives were heard and incorporated into future research, and seven PPI outcomes have been identified, which provide a deeper understanding of the research problem from the perspective of new mothers.

There has been great value in the research team gaining greater knowledge of the effect that work-related psychological distress in midwifery has on new mothers, before conducting further research in this area. The experience of childbirth should be a positive one, yet for these new mothers, this was obstructed by midwives experiencing work-related psychological distress. The challenge will be to address this problem through research, and to examine whether the perceptions of new mothers change in light of an effectively supported workforce. Future research should develop and evaluate an online intervention to support midwives experiencing work-related psychological distress, considering these findings. Should the results of this research represent broader perspectives, both national and international strategies and frameworks to improve maternity care could usefully prioritise the support needs of midwives and the needs of maternity service users in equal measure.