There is an increasing body of evidence from surveys to suggest that burnout is not uncommon in the midwifery workforce (Hildingsson et al, 2013; Henriksen and Lukasse, 2016; Fenwick et al, 2018a; Hunter et al, 2019; Stoll and Gallagher, 2019), with potentially better outcomes for midwives working in a caseload model (Newton et al, 2014; Dixon et al, 2017; Dawson et al, 2018; Fenwick et al, 2018b). However, there are conflicting findings on whether age, length of experience or weekly hours influence outcomes, which might be explained by differences in samples or methods of analysis.

The influence of working practices on job satisfaction are commonly captured through the analysis of open-ended survey responses. The ability for midwives to form relationships with women and have time to provide advice and high-quality care has been linked to job satisfaction, whereas working conditions, such as high or unreasonable workloads, working long shifts/hours with no breaks, staff shortages, or a lack of recognition or role support have contributed to job dissatisfaction (Sandall, 1998; Harvie et al, 2019; Cull et al, 2020). However, there is a gap in the evidence on how shift length and other working practices, such as the ability to take rest breaks, finish on time or intershift recovery, may influence outcomes, and no existing survey instrument incorporates these aspects.

Bespoke survey items can be developed to answer specific research questions, but this approach is not without its challenges. The design of a new survey instrument requires careful planning, as response errors can arise when participants attempt to answer questions, increasing the risk of invalid or incomplete data (Collins, 2015; Hofmeyer et al, 2015). Drawing on a model arising from the fields of cognitive psychology and survey evaluation, there are four distinct stages that must be completed for a participant to be able to answer a survey question: comprehension, retrieval of information, judgement and reporting an answer (Groves et al, 2011). If participants do not interpret a question in a way that was intended by the researcher, then conclusions will be flawed, or if different participants interpret the question in different ways, systematic bias could be introduced (Willis, 2005; Collins, 2015).

The retrieval process may depend on whether factual or attitudinal information is required, timescales and frequency of an event (Ryan et al, 2012; Collins, 2015). When participants answer survey questions, they make a judgement based on their understanding of the question, whether they have the information to answer it and whether they are motivated enough to answer accurately (Willis, 2005; Collins, 2015). Response options can affect the way a participant reports an answer (Collins, 2015).

A new survey was created in December 2018; the objectives were to analyse the association between individual characteristics, work-related factors and working practices and their effect on emotional wellbeing outcomes of midwives working in the NHS across the UK. Items for inclusion were informed by the survey's objectives, a review of the literature, national guidance on staff-reported measures related to midwifery safe staffing indicators (National Institute for Health and Care Excellence, 2015) and measures of key items from a preliminary survey of heads of midwifery that explored the working practices of midwives in NHS hospital settings (Dent, 2020).

Single-item measures assessed the outcomes of work-related stress, job satisfaction, being pleased with their standard of care and thoughts about leaving midwifery. Burnout was measured with the Copenhagen Burnout Inventory (Kristensen et al, 2005), which has previously been validated among midwives, so these items were not tested, and neither were individual characteristics. The rationale for including working practices items are shown in Table 1.

Table 1. Rationale for inclusion of working practices items in first draft of survey

| Item | Rationale |

|---|---|

| Shift length | Inconsistent findings in nursing literature |

| Advance release of off-duty | Possible impact on ability to plan personal/social life with any certainty |

| Frequency of finishing shift on time* | All items may be directly or indirectly related to staffing issues (National Institute for Health and Care Excellence, 2015) |

| Inability to take a rest break | *Inconsistencies in NHS trusts documenting these in the first survey (Dent, 2020) |

| Formal methods in place to record missed rest breaks* | |

| Called away from mandatory training session in past year | |

| Length of rest break | Results from first survey (Dent, 2020):

|

| Maximum number of consecutive shifts that can be scheduled | |

| Scheduled to work a day shift within 24 hours of finishing night shift |

Methods

This article presents the process of survey development and the two pre-testing methods that preceded a conventional pilot: cognitive interviews and a discussion group. Cognitive interviews are specifically designed in-depth qualitative methods, structured around a four-stage answer model, to understand how participants might have interpreted a question and how they came to formulate an answer. These processes are then analysed to assess whether the questions were measuring what they were intended to and to what level of accuracy (Presser et al, 2004; Groves et al, 2011). The aim of the interviews was to test question wording and proposed content to support the face and content validity of the new instrument. The discussion group was incorporated as an additional form of review, with the aim to specifically consider the optimal wording of one survey item.

Participants

To be eligible for inclusion, participants needed to be registered with the Nursing and Midwifery Council and currently working as a midwife in an NHS trust, thus reflecting the target population of the finalised survey. Student midwives or midwives who did not work in a clinical role were excluded.

The cognitive interviews were based on a purposive theoretically driven non-probability sample. Country/region of the UK in which the midwife worked was prioritised in the sampling criteria (because of likely differences in working practices). A minimum of two interviews needed to be conducted with midwives working in each of: Northern Ireland, Scotland, Wales and London. As a result of the large geographical area, and to allow flexibility in recruitment, a minimum of four interviews was set for those working in the north, south and east of England. To ensure a balance of opinions, secondary sampling criteria included at least four interviews with midwives with less than 2 years' experience, four with 10 or more years' experience; four in those aged under 35 years and four in those aged 45 years or older.

Participants were recruited via advertisements on two midwifery network social media sites on Facebook. All sampling criteria were achieved (Table 2), with 24 interviews being conducted over three consecutive rounds of testing between July and November 2019.

Table 2. Characteristics of cognitive interview participants

| Region | Experience (years) | Age (years) | Band | Data collection method |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| London | 6 | 30 | 6 | Face-to-face |

| 7 | 34 | 6 | Face-to-face | |

| Southwest England | 13 | 49 | 6 | Face-to-face |

| 11 | 59 | 6 | Telephone | |

| Southeast England | 9 | 33 | 7 | Face-to-face |

| 5 | 55 | 6 | Face-to-face | |

| East England | 8 | 46 | 7 | Face-to-face |

| 1.5 | 38 | 6 | Face-to-face | |

| 22 | 44 | 6 | Telephone | |

| East Midlands | 23 months | 23 | 5 | Face-to-face |

| 35 | 60 | 6 | Face-to-face | |

| Yorshire and The Humber | 3 | 54 | 6 | Telephone |

| 7 | 50 | 6 | Telephone | |

| Northwest England | 20 months | 50 | 5 | Face-to-face |

| 13 | 46 | 6 | Telephone | |

| 24 | 51 | 6 | Telephone | |

| Northeast England | 1.5 | 39 | 5 | Face-to-face |

| 18 | 49 | 6 | Telephone | |

| Scotland | 6 | 39 | 6 | Face-to-face |

| 6 | 47 | 6 | Face-to-face | |

| Wales | 8 | 37 | 6 | Face-to-face |

| 6 | 39 | 6 | Face-to-face | |

| Northern Ireland | 4 | 26 | 6 | Face-to-face |

| 14 | 44 | 7 | Face-to-face |

Note: to protect participants' identities, the ID numbers assigned in Table 3 do not correspond to the order shown here

Midwives responding to the call for participation were asked if they would consent to being a ‘survey champion’, which would involve promoting participation in the finalised online survey by sharing the survey link with other midwives, for example, through social media groups. A total of 44 midwives were recruited as survey champions from various regions of the UK (23 took part in the interviews). For practical reasons, a convenience sample of five midwifery academics were recruited for the discussion group from a university in the east of England via internal email invites, which took place in February 2020. The researcher had a working relationship with these five participants.

Data collection

All midwives taking part in the interviews completed the survey online, administered through the secure online platform ‘online surveys’, either face-to-face or while on the telephone with the interviewer. Interviews were audio recorded and assigned an identification number. Interviews ranged in length from 26–93 minutes, with a mean duration of 47 minutes.

Two main techniques that can be used in cognitive interviews are think-aloud and verbal probing (Willis, 2005; Campanelli, 2008; d'Ardenne, 2015), both of which were used. With think-aloud, the participant talks out loud when reading the question and verbalises thoughts about their answer, while the interviewer makes notes that may indicate any problems with a question (d'Ardenne, 2015). Verbal probing involves asking specific questions related to a question to target specific aspects, such as recall or comprehension (Ryan et al, 2012).

An interview protocol had been developed to structure each individual interview and serve as a data collection instrument (field notes and observations). Midwives were asked to answer a series of survey questions while thinking-aloud and advised in advance where to pause to facilitate standardised probes (included in the protocol), such as ‘how easy or difficult was it to answer this question?’. Spontaneous probes were used as necessary; for example, if a participant changed their original answer: ‘I saw you changed your answer for question X, can you say what you were thinking at the time?’.

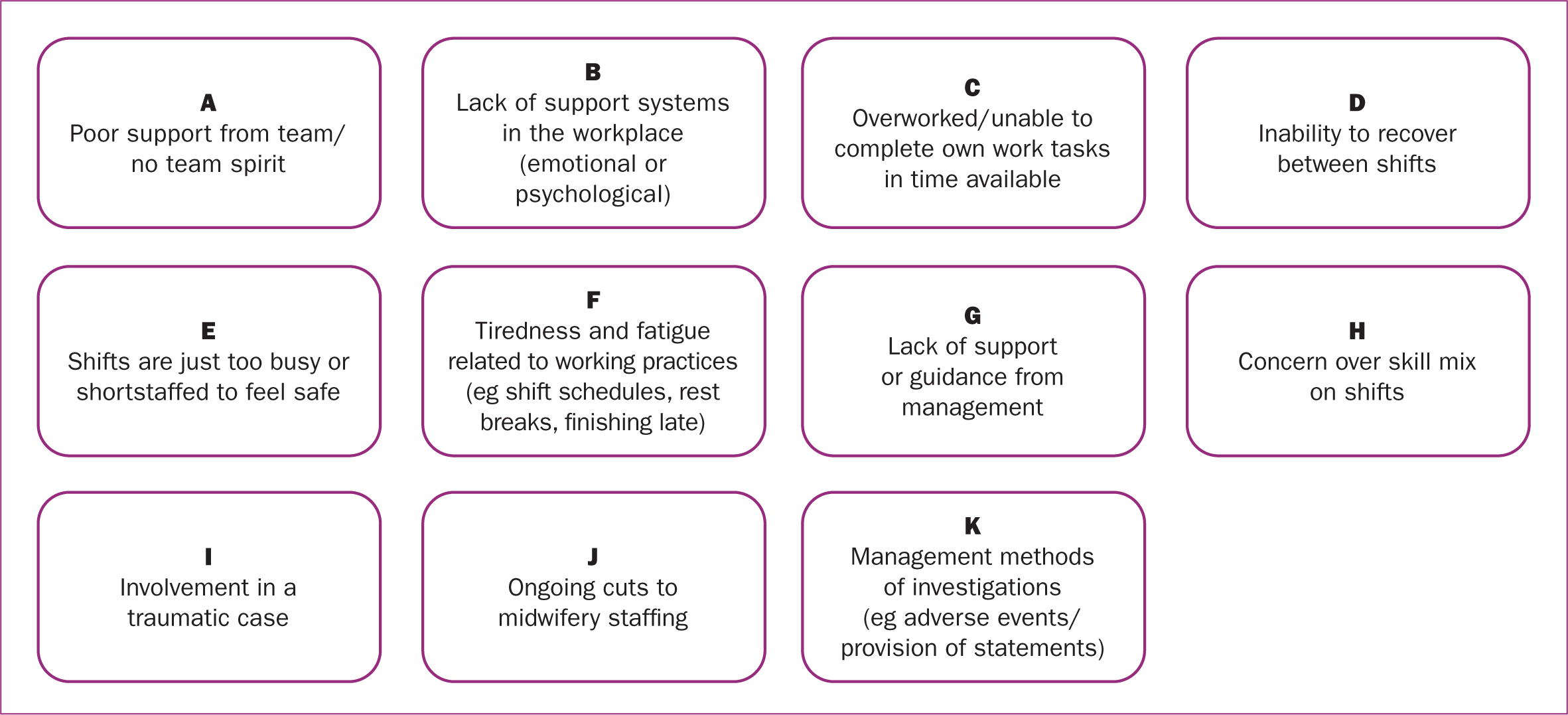

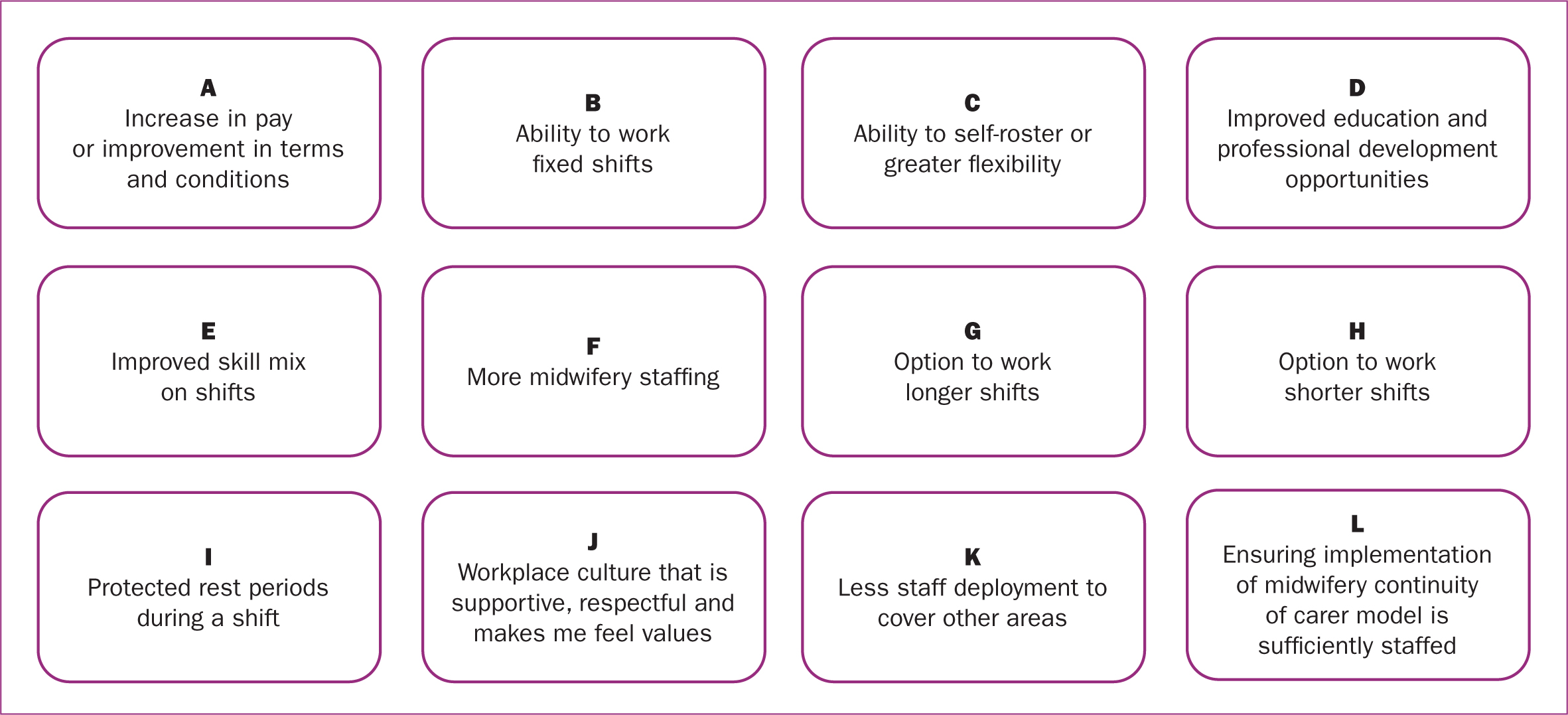

Cognitive testing methods can also include card sorts (Collins, 2015), which are useful visual methods that permit exploration of an individual's unique interpretation of complex concepts (Willis, 2005). Card sorts were used as a systematic means to inform the content of two new multi-response items that would complement the single item outcome measures of work-related stress and job satisfaction. The card sort for work-related stress (Figure 1) was developed as part of the interview process based on responses to spontaneous probes in the first 12 interviews. In subsequent interviews, only those who selected a positive response to work-related stress were asked to complete the card sort. Items for the job satisfaction card sort were prepared in advance, derived from key aspects arising from a review of the literature and used at the end of all interviews (Figure 2). The card sorting process required midwives to decide on the importance of items by placing cards in a ranked order or, if items were not considered important, they could be left out.

Following completion of the interviews, the survey item on shift length continued to create comprehension difficulties. Rather than rely solely on the judgement of the interviewer, a 1-hour, semi-structured discussion group was conducted to specifically consider the optimal wording of this question. The format drew on cognitive interviewing techniques (Willis, 2005; Collins, 2015). Vignettes were used to present hypothetical scenarios that demonstrated the types of comprehension problems found for the question on shift length. No audio recording was made but verbal feedback was documented, with the aim to reach a consensus on the wording.

Data analysis

The primary unit of analysis in the interviews was respondents' interpretations of the individual survey items, and not their survey answer. The full transcription of cognitive interviews is often unnecessary as it is the interviewer notes that provide the main unit of analysis, but, as a novice cognitive interviewer, JD transcribed all interviews verbatim to check the accuracy of interview notes. Interview data were then reduced and organised through two framework matrix methods (d'Ardenne and Collins, 2015), which facilitated descriptive and explanatory analysis on an item-by-item basis, to guide decisions on whether survey items should be removed, modified or retained. Results were analysed after interviews 12, 18 and 24 (final interview). The interview protocol was updated after each review to reflect any changes in question or answer format.

Ethical considerations

Ethical approval was granted by the University of Hertfordshire Health, Science, Engineering and Technology Ethics Committee with Delegated Authority for the cognitive interviews (approval number: HSK/PGR/UH/03668) and the discussion group (approval number: HSK/PGR/UH/04063). Written informed consent was obtained for each method prior to any data collection.

Results

The pre-testing process resulted in several modifications to the original survey items (Table 3). Only one of the work-related items (travel to work time) required modification. Of all the working practices items, the question on shift length appeared to be the most problematic. The potential for response error was noted as a result of midwives working a range of shift lengths to make up weekly hours, working on-calls, differences in day and night shift lengths, working beyond the end of their shift or confusion with the question. Participants in the discussion group agreed that the optimal format of this question would be to split it into separate questions for day and night shifts, remove the reference to rest breaks and to provide an explanatory statement regarding any time spent working beyond the end of the shift. New questions were created to explore mixed shift lengths and issues related to on-call working.

Table 3. Examples of response problems

| Initial wording/revisions | Response problem | Final wording |

|---|---|---|

| 1. What is your estimated time to travel to work on a typical day?Modified after first review | 1. Comprehension and ability to answer: CI007 queries whether the question meant a return journey | What is your estimated time to travel to work (one-way) on a typical day? (For community midwives that go straight to home visits, use travel time from home to any base location) |

| 2. What is your estimated time to travel to work (one-way) on a typical day? | 2. CI016 did not feel she could answer as she works in community and goes straight to visits that vary in distance | |

| 1. What is the total shift length (including any rest break) you are scheduled to work? Modified after first review | 1. Comprehension and ability to answer: question does not account for mixed (shorter) shift lengths to make up weekly hours. Question does not account for midwives who work a variety of shift lengths. Potential for response error if answer includes time working beyond end of shift. Response categories: no option to acknowledge extended working hours for on-call work | How long are your day shifts? (Do not include any time spent working beyond the end of your shift - you will be asked about this later). If you work different shift lengths in the day, select the most common shift length worked.How long are your night shifts? (Do not include any time spent working beyond the end of your shift) |

| 2. What is the total shift length, including any rest break (even if not taken) that you are scheduled to work on a typical shift? If you work different shift lengths, select the most common shift length worked | 2. Ability to answer: question does not account for differences between day and night shift length. CI022 worked 12.5 hour shifts with 1-hour break was unsure whether to answer 11.5 or 12.5 for shift length | |

| New question added after first reviewDo you ever have to work mixed shift lengths (eg shorter shifts of 6 hours) to make up your weekly contracted hours? | Comprehension: CI022 and CI023 thought the answer was yes, but not for making up hours, instead for study days/training or on a ‘when needed’ basis | Do you ever have to work mixed shift lengths (eg shorter shifts to make up weekly hours, because of study days/training or for other reasons)? |

| New question added after first reviewDo you ever have to work on-calls? (Positive answer triggering further question on number of on-calls a week) | Ability to answer: participants who worked on-calls advised on-call period was calculated over a 1-month period. In one unit, midwives used to have to work on-calls because of staffing shortages, but this practice has been stopped as staffing levels have increased | Do you currently have to work on-calls? (Positive answer triggering further question on number of on-calls in a 1-month/4-week period) |

| New conditional response added after first reviewIf you work on-calls, do you consider that your working pattern allows you sufficient recovery time before being back on duty? | No response problems | Question format retained |

| 1. How many unpaid rest breaks are usually scheduled into your shift? | 1. Comprehension: the term ‘unpaid’ appeared to confuse CI007, CI010 and CI011, believing breaks/missed breaks were paid | How many rest breaks are you supposed to have in the most common shift length that you usually work (even if they are cut short if not taken)? Do not include ‘informal’ tea breaks |

| 2. How many unpaid rest breaks are usually scheduled in your shift (even if they are cut short or not taken, how many are you supposed to have)? | 2. Comprehension: the term ‘scheduled’ confused CI013, who believed this to mean a specific timeframe for a break, but was also unsure how to answer when breaks varied according to shift length worked |

The terms ‘unpaid’ and ‘scheduled’ appeared to cause confusion in the question on rest breaks, and so they were removed, with no further problems observed. During the first 12 interviews, midwives provided reasons for missed breaks or not being able to finish on time. In subsequent interviews, two new survey items were added to explore this. Retrieval probes explored how easy or difficult it was to remember finishing on time or the inability to take rest breaks in the past month and past 3 months. All thought it was easy to remember this for the past month, but only half felt confident for a 3-month period, so both questions retained a 1-month recall period. There were no problems identified for the remaining working practices items.

No problems were observed for any of the single-item outcome measures. A general probe explored how easy or difficult it was to answer the questions on job satisfaction and standard of care. Some verbalised difficulty in answering, often reflecting on very satisfying aspects of their jobs alongside frustrations, while answers on their standard of care appeared to be based on the type of care they wanted to give. However, all were able to decide on answers that they felt were appropriate.

The reasons given for work-related stress and job satisfaction, collated from the card sorts (Figures 1 and 2), were retained for inclusion in new survey items, with minor amendments to some of the wording. Based on the feedback, nine further answer options were included for job satisfaction, which included separating opinions on the continuity of care model into two statements to reflect positive and negative views of working in this model.

General probes in the first 12 interviews explored options for expanding the questions on standard of care and thoughts about leaving. All midwives thought this would be useful. Reasons influencing their standard of care were focused on factors that had a perceived detrimental impact. A new multi-response item was created and tested in the final 12 interviews, resulting in a list of 13 reasons.

A total of 21 reasons were collated from those that indicated thoughts of leaving, which conditionally appeared in a new question if a positive answer was given.

Discussion

The cognitive interviews enabled the systematic assessment of the content and quality of the new survey instrument (Collins, 2015; Willis, 2015). The results show the importance of pre-testing survey items from a respondent's perspective, as potential comprehension and response problems became evident during the process. If these issues had not been identified prior to survey administration, it could have led to response errors and potentially misleading conclusions, threatening the validity of the results.

The use of cognitive interviews to evaluate surveys in healthcare research has been well documented (Drennan, 2003; Ryan et al, 2012). In recent years, cognitive interviews have also been used as part of the validation process for survey instruments in midwifery settings (Martin et al, 2014; Stahl et al, 2017; Kalu et al, 2020). Focus groups offer an alternative form of review, although they are more exploratory, and so are useful in the early stages of survey development (Blake, 2015). As a pre-testing method, focus groups can produce different findings to cognitive interviews. For example, comprehension problems are more likely to go undetected, as participants may be unwilling or feel uncomfortable in a group environment, they may not have the opportunity to voice their own interpretations of a question, and responses to probing in focus groups have resulted in more generic opinions and less clearly formulated answers (Blake, 2015; Collins, 2015; Sugovic et al, 2016). Therefore, cognitive interviews were deemed the optimal pre-testing method.

Midwives in the present study had the skills and ability to understand the different interview techniques and were adept in verbalising their thought processes, minimising the chance of the interviewer missing any response problems. By focusing on the perception of the target population, the survey questions were refined to better suit the various ways in which midwives work across the UK and how they might interpret the questions. This is evident in the modifications and addition of items related to working practices. Feedback from the interviews also enabled the expansion of specific question and answer options to explore reasons associated with a range of working practices.

The construct of the single-item outcome measures were all measured as concepts-by-intuition, the operationalisation of which assumes that the meaning is immediately obvious to an individual and that they can express their views to a simple question (Saris and Gallhofer, 2014). The cognitive interviews confirmed midwives' comprehension and judgement of these measures, and appeared to capture accurate accounts of how midwives perceived their ability to do their job to a standard that they were pleased with, even when some found it a hard question to answer. Midwives appeared to base their answer for job satisfaction on an overall assessment of both positive and negative factors. Participants enjoyed the inclusion of card sorts, which built the concepts of work-related stress and job satisfaction. These may not have been identified through the literature review alone.

Limitations

The convenience sample of midwifery academics could be criticised for not being representative of the target population (Fain, 2013). However, this group had knowledge about working practices as they were linked to different NHS hospital sites as part of their job. In addition, the revised format of the question on shift length was tested in the later pilot study.

Cognitive interviews could be criticised for a lack of standardised practice for data analysis (Ryan et al, 2012). However, the systematic approach of the framework matrix method is specifically designed to be transparent and open to scrutiny, as each matrix details the analytic process and interpretations (audit trail), which can help findings gain credibility (Collins, 2015).

While the cognitive interviews were effective in assessing whether participants understood the questions, it is possible that a different sample may have identified other problems (Ryan et al, 2012), or proposed alternative reasons when building the multi-response options. However, the reasons listed were frequently similar among participants, so were thought to provide a good starting point to better understand factors that may contribute to midwives' emotional wellbeing.

Conclusions

The findings show that designing a new questionnaire is a complex process. Cognitive interviews precede and complement a conventional pilot by revealing problems that may not have been anticipated by the researcher. Cognitive pre-testing can be an effective method to confirm the relevance and usability of bespoke survey items and offers opportunities to improve wording and content before administration in the field to reduce potential sources of error, supporting the face and content validity of the survey.

Key points

- Surveys are regularly used within midwifery research to explore factors that may be associated with midwives' emotional wellbeing, yet there is a lack of standardised questionnaires that are specifically designed to explore the effect of working practices on outcomes.

- This research sought to test the face and content validity of a new survey instrument by assessing midwives' comprehension of bespoke survey items related to working practices.

- The findings identified and validated previously unexplored measures that may influence emotional wellbeing outcomes in midwives.

- Inclusion of these measures may enhance understanding of factors that influence emotional wellbeing outcomes in midwives.

CPD reflective questions

- What are the advantages and disadvantages of think-aloud techniques in cognitive interviews?

- What other pre-testing methods might be used to pre-test questionnaires, and at what point might they sit in the survey development process?

- In addition to evaluating survey questions, what other types of documents or information can be tested with cognitive interviews?