There is copious evidence regarding the experiences of asylum-seeking women accessing maternity care in the UK (Briscoe and Lavender, 2009; Feldman, 2013; Lephard and Haith-Cooper, 2016; McKnight et al, 2019), but this is not the case regarding the experiences of midwives themselves. In 2021, the UK received 485 480 asylum applications (Home Office, 2021). When compared to other European countries, this is a relatively low number; however, media and political discourse often present the volume of asylum seekers as a ‘crisis’ or ‘threat’ (Hill, 2022). This can negatively alter public perceptions towards asylum seekers and increase the discrimination they face.

In many ways, midwives are practicing in a time of crisis. It has been reported that for every 30 newly qualified midwives, 29 leave the profession (Royal College of Midwives (RCM), 2018). Management systems are alleged to be bullying and hierarchical (Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists (RCOG), 2018), and midwives are burnt out and unsatisfied with the quality of care they are able to deliver (RCM, 2021). In-keeping with welcome developments in policy to reduce racial inequalities in maternal outcomes (RCOG, 2020a; RCM, 2020a), this systematic review aimed to provide insight into the experiences of midwives when caring for asylum seekers.

There were two main research questions to address:

- What are midwives’ experiences when caring for asylum-seeking women accessing maternity services?

- What could be learned from these experiences to improve care outcomes for women seeking asylum?

Dehumanisation of black women's bodies

It is important to recognise the intersectional discrimination facing asylum-seeking women in regards to their ethnicity. Of those applying for asylum in 2021, the predominant nationalities were Iranian, Eritrean, Albanian, Iraqi and Syrian (United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees, 2021). These are all minority ethnic groups in the UK, and some of these women will be black or Asian.

In the UK, being black or Asian is an additional risk factor for poor outcomes in pregnancy, including maternal and neonatal death (Knight et al, 2019). Of the 217 UK women who died between 2016 and 2018 as a result of causes associated with their pregnancy, five were asylum seekers or refugees (Knight et al, 2019), which equates to 2.3%. In the UK, asylum seekers and refugees comprise only 0.26% of the population (United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees, 2021). Therefore, it is clear that asylum-seeking women from minority ethnic groups experience multiple disadvantages and are at a higher risk of maternal death when compared to white women who hold British citizenship.

The historical treatment of black women contextualises a legacy of inequality and exploitation, particularly in regards to obstetrics (Owens and Fett, 2019; Horn, 2020). The UK's colonial history of racial exploitation may influence how individuals engage with care in the present. For example, the idea that black people do not feel pain (Owens and Fett, 2019) may subconsciously impact how midwives assess pain in black women.

Asylum-seeking women in the UK

Asylum seekers often describe feeling that they occupy liminal spaces while waiting to be granted refugee status (Pangas et al, 2018). Current legislation arguably perpetuates the economic, social and cultural marginalisation of asylum seekers in the UK (Balaam et al, 2016). Asylum-seeking women experience multiple barriers when accessing maternity care because of language barriers, fear of being charged for care, dispersal mid-pregnancy and concern over information-sharing between the Home Office and health services (Haith-Cooper and McCarthy, 2015; Puthussery, 2016; McKnight et al, 2019; Frank et al, 2021; Arrowsmith et al, 2022). The literature highlights how asylum-seeking women may be psychologically vulnerable as a result of a history of sexual violence or post-traumatic stress disorder (Feldman, 2013; Phillimore, 2015).

Some literature reports that midwives are perceived positively by women seeking asylum (McKnight et al, 2019; Frank et al, 2021; Arrowsmith et al, 2022). Conversely, some women experience stereotyping, hostility, explicit racial abuse and indifference (Asif et al, 2015; Phillimore, 2015; Balaam et al, 2016; McKnight et al, 2019).

This systematic review considered the experiences of midwives providing care to asylum-seeking women, to reflect on why outcomes are poor and how care can be improved.

Methods

A literature search was performed in April 2021. This included searching the Directory of Open Access Journals, Scopus, JSTOR, CINAHL Complete, ScienceDirect and MEDLINE. Google and Google Scholar were also used to identify any relevant unpublished studies. The search terms used were: ‘asylum seekers’ OR ‘refugees’ AND ‘midwives experiences’ OR ‘attitudes’ OR ‘feelings’ AND ‘UK or United Kingdom’.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

The inclusion criteria were initially UK-based research papers about the experiences of healthcare professionals providing maternity care to asylum-seeking women. However, this search was expanded and two articles from outside the UK were included because of a lack of available literature on this topic. As there was a significant lack of literature available, articles published between the broad timeframe of 2000–2022 were included. Two articles were included that detailed the experiences of student midwives, rather than qualified healthcare professionals. Any articles that did not discuss a research project or that did not explicitly focus on healthcare professionals’ perspectives were excluded.

It became clear that the terms ‘asylum-seeker’, ‘refugee’ and ‘migrant’ are often used interchangeably. Therefore, the latter terms were included in further searches, to ensure papers concerning the correct population were identified.

Selection of literature

Historically, quantitative research has been regarded more highly than qualitative, as a result of the belief that numerical data analysis is analytically more robust, with less potential for researcher bias (Loder et al, 2016). As qualitative research is only recently gaining precedence among decision-makers for healthcare policy and practice, it was pertinent for this selection process of qualitative papers to be robust.

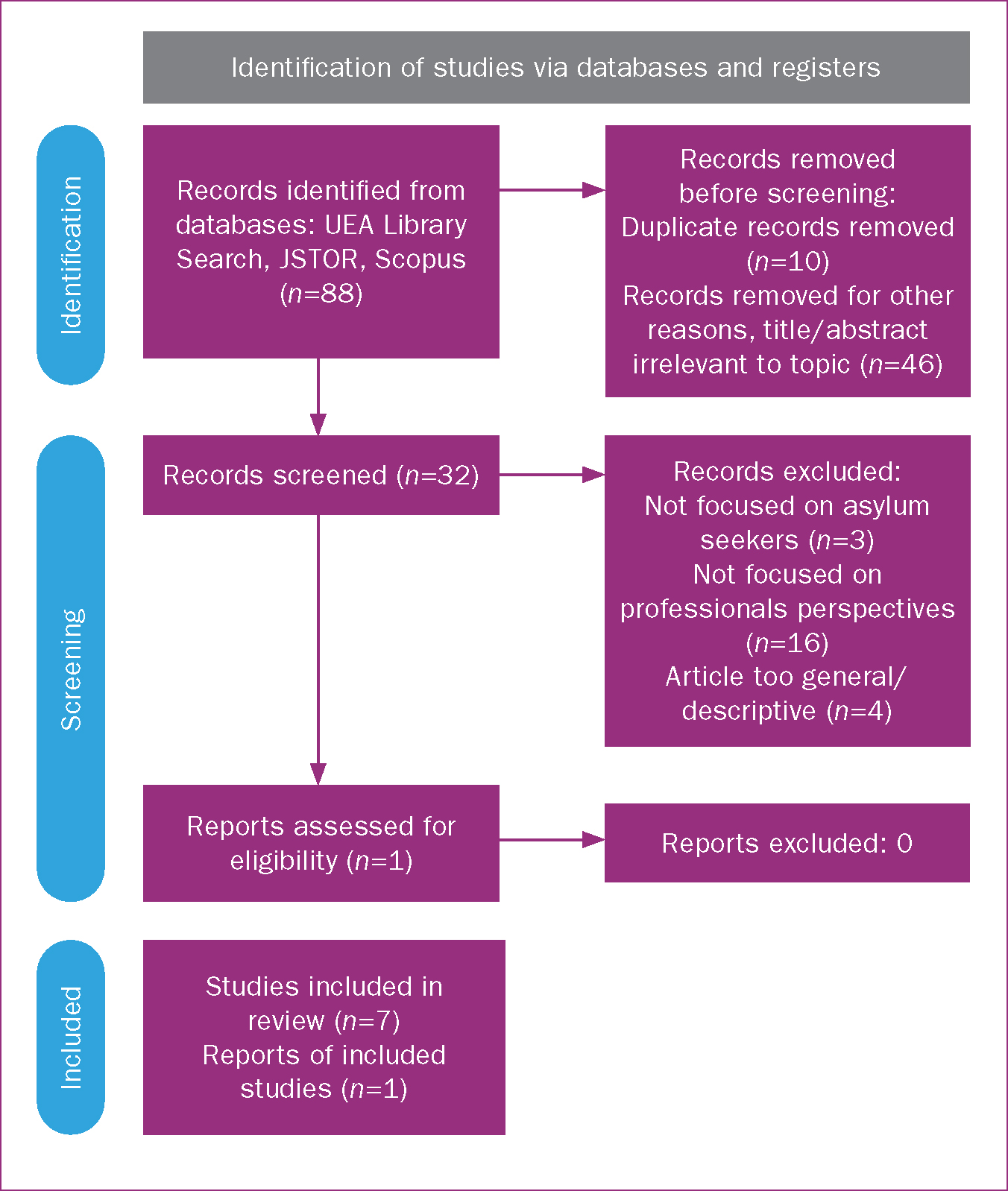

The preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses flow diagram (Figure 1) was used to structure the literature screening process, and the Critical Appraisal Skills Programme qualitative article checklist was used to assess the quality of articles included in the review. The flow diagram is often used in biomedical systematic reviews and gave transparency to the selection process. Although this review is underpinned by sociological theory, as well as medical theoretical frameworks, organising the research in a similar manner to reviews featured in the Cochrane database was felt to enhance rigour. Although both methods of literature selection and screening are user-dependent and possess limitations, both are endorsed by the Cochrane Qualitative and Implementation Methods Group (Long et al, 2020) and were deemed suitable.

Eight studies were identified for inclusion in the review. Table 1 shows details of the studies.

Table 1. Study characteristics

| Authors and date | Location and sample | Research design | Identified themes |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Cross-Sudworth et al (2015) | West Midlands, UK 213 midwives | Retrospective total population semi-structured postal questionnaire |

|

| 2. Harper-Bulman and McCourt (2010) | West London, UK Unknown number of midwives | Semi-structured interviews and focus groups |

|

| 3. Kurth et al (2010) | Basel, Switzerland 10 healthcare providers, including midwives | Semi-structured interviews with health care providers |

|

| 4. Bennett and Scammell (2014) | One NHS Trust, Northern England 10 midwives | Semi-structured interviews |

|

| 5. Haith-Cooper and Bradshaw (2013a) | University of Bradford, UK 11 student midwives | Two focus groups, three individual interviews |

|

| 6. Haith-Cooper and Bradshaw (2013b) | Continued analysis of data from above study | Critical discourse analysis of secondary data |

|

| 7. Tobin and Murphy-Lawless (2014) | Dublin, Ireland 10 midwives | In-depth unstructured interviews |

|

| 8. Gaudion and Allotey (2008) | Hillingdon, UK Unknown number of midwives | Focus group discussions and semi-structured interviews |

|

Thematic analysis

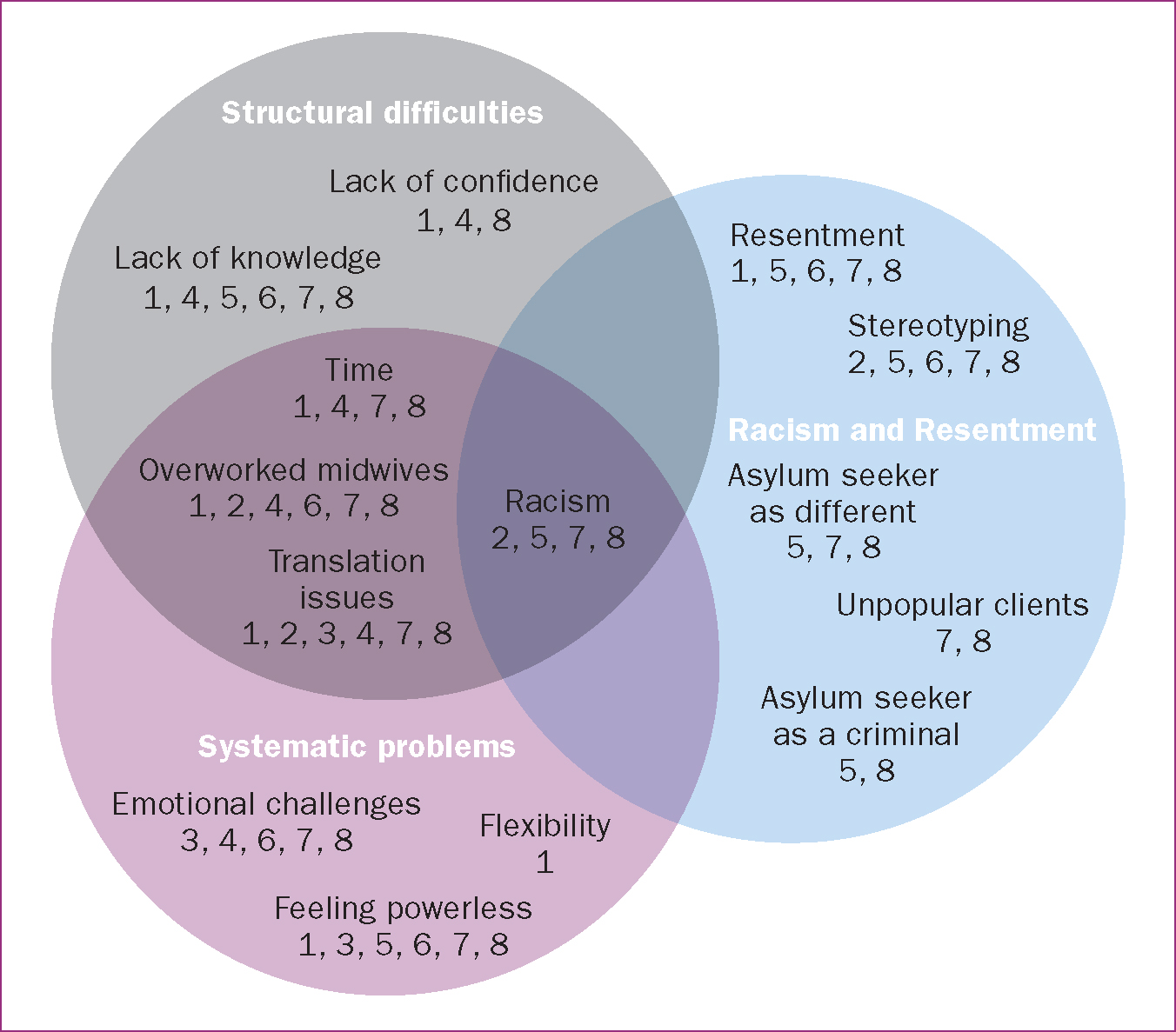

All eight studies were analysed for thematic similarities. Themes were identified through comprehensive screening of the papers and agreed upon by the author and an academic supervisor to limit bias. The themes were: resentment and racism, structural difficulties and systematic problems (Figure 2).

Quality appraisal

Setting

Two of the identified studies were conducted outside of the UK,Tobin and Murphy-Lawless (2014) in Ireland and Kurth et al (2010) in Switzerland. Although this review focused on the experiences of midwives in the UK, these papers were included because of their specific study design, which accurately fit the inclusion criteria.

Relationship between researcher and participant

For all included studies bar Cross-Sudworth et al (2015), the racial identities of, and consequential relationships between, researcher and participant were not considered. Research has shown that participants in ethnically homogenous focus groups were more likely to make potentially controversial comments relating to ethnic differences (Greenwood et al, 2014). This is relevant because if a white midwife is being interviewed by a researcher of a different ethnicity on asylum-seeking issues, the midwife may be reticent to share their true perceptions for fear of being deemed racist. However, a white midwife being interviewed by a white researcher may have been more inclined to use ‘us vs them’ terminology.

Dynamics within a focus group

Studies that featured focus group discussions (Gaudion and Allotey, 2008; Harper-Bulman and McCourt, 2010) did not consider the interpersonal dynamics between participants. These papers underestimated how focus groups themselves constitute a unique social context (Kitzinger, 1994). Of these studies, no consideration was given to the degrees of seniority among midwives and students in the groups and how this could impact the discussion. This could have led to self-censoring (Bloor et al, 2001; Carey and Asbury, 2012).

Participant demographics

Five papers focused exclusively on the experiences of health professionals or students (Haith-Cooper and Bradshaw, 2013a, b; Bennett and Scammell, 2014; Tobin and Murphy-Lawless, 2014; Cross-Sudworth et al, 2015), and three also considered broader debates regarding the experiences of asylum-seeking women themselves (Gaudion and Allotey, 2008; Harper-Bulman and McCourt, 2010; Kurth et al, 2010). The papers that analysed asylum seekers focused conceptually on the experiences of asylum-seeking women themselves, rather than health professionals (Gaudion and Allotey, 2008; Harper-Bulman and McCourt, 2010).

Two papers focused on the perceptions of student midwives (Haith-Cooper and Bradshaw, 2013a, b). The papers were part of a set following a doctoral study to develop a theoretical framework to aid understanding of the issues asylum-seeking women faced in pregnancy. These papers captured the students’ perceptions prior to formal education on this topic; this is significant, as many registered, practising midwives may have received a similar degree of limited instruction during their pre-registration education and may share comparable beliefs.

The number of health professionals interviewed in each study varied. Most studies (Kurth et al, 2010; Haith-Cooper and Bradshaw, 2013a, b; Bennett and Scammell, 2014; Tobin and Murphy-Lawless, 2014) interviewed between 10 and 11 health professionals. In one study (Harper-Bulman and McCourt, 2010), the number of those interviewed was unknown. Where focus groups were used, the number of participants was also unclear (Gaudion and Allotey, 2008; Harper-Bulman and McCourt, 2010). The study with the largest population analysed survey responses from 213 midwives (Cross-Sudworth et al, 2015). A total of approximately 303 midwives and student midwives were represented by this systematic review, which is a relatively small sample and influences the generalisability of results.

Results and discussion

The thematic narratives were divided into three cateogries and then compared to the current realities of working as a midwife in the UK. These categories are listed below, with related subcategories also described.

Racism and resentment

Resentment

It was reported that ‘the combined impact of ignorance, fear and increased workload sometimes resulted in frustration and resentment’ (Tobin and Murphy-Lawless, 2014). Some midwives described feelings of ‘concern and frustration in trying to do “the right thing” for women’ (Cross-Sudworth et al, 2015).

‘[Asylum-seeking] women often perceived the frustration and resentment … this compromised the midwife's ability to develop a relationship with them’

(Tobin and Murphy-Lawless, 2014).

Some midwives were described by researchers as having a ‘frank expression of hostility’ (Gaudion and Allotey, 2008) towards asylum-seeking women, mirroring current UK Home Office policy (Weller et al, 2019). Student midwives also demonstrated explicit resentment towards this demographic.

‘We're only a small island, so there's got to be rules and there's got to be cut-offs as to who can come… there isn't an infinite amount of housing for everybody to go around.’

Haith-Cooper and Bradshaw, 2013a

The UK media commonly presents an image of the country as a container, bursting with the pressure of housing asylum-seeking families (Pruitt, 2019), which is reflected here. These are clear examples of how attitudes can be shaped by emotive media discourse and policy.

Dishonesty

Asylum seekers were perceived as liars. Women were not believed when reporting they could not understand English, with some midwives trying to prove their perceived dishonesty. Where asylum-seeking women are not believed, the risk of health complaints being dismissed increases, and outcomes may be poor (Henderson et al, 2013).

‘[Asylum-seeking women] made up a reason so that they can stay in this country because there are … more employment prospects.’

Haith-Cooper and Bradshaw, 2013a

‘I test them by saying something inflammatory just to see if they understand.’

‘They claim they do not speak English.’

Midwives did not always treat asylum-seeking women with compassion, and there was a lack of patience for asylum-seeking women who did not understand the system.

‘I'd say “well, do you not realise the importance of antenatal care?"…I would get a bit annoyed, but I would be the same if there was an Irish woman … because … you just don't know if they're high risk and they are HIV-positive … and I suppose I'm being a little bit racist or whatever.’

Tobin and Murphy-Lawless, 2014

The asylum-seeker as criminal

Media discourse is capable of effectively shaping the views of a society (Machin and Mayr, 2012; O'Regan and Riordan, 2018). It is possible that media discourse, which conflates asylum seekers with criminal activity (O'Regan and Riordan, 2018; Tong and Zuo, 2019), may influence the opinions of midwives. Throughout the interviews analysed in this systematic review, asylum seekers were often associated with criminal behaviour. The paper focusing on student midwives highlighted the same issue:

‘She was from Zimbabwe or one of those places … obviously here illegally … it creates more work.’

‘Go to court … question illegal immigrants and asylum seekers. And there's a judge there and they have a barrister … put the case against them’

(Haith-Cooper and Bradshaw, 2013a).

Conservative beliefs and avoidance of change are often involved in justifying inequality (Van de Vyver et al, 2016).This review will go on to explore how these ideological beliefs are more likely to be adopted when midwives are under pressure.

Stereotyping

The healthcare system does not always give adequate consideration to the historical context in which care is provided. It can be emotionally jarring to consider the UK's colonial past, but it is pertinent to understanding the discrimination that women from minority ethnic groups face.

Gaudion and Allotey (2008) focused on a maternity unit located close to Heathrow Airport. The researcher reported a noticeable tension between ‘the issue of people's immigration status and the need to work with them regardless’ (Gaudion and Allotey, 2008), which was compounded by broad assumptions regarding individuals’ rights to be in the UK.

‘We get all these illegals from Heathrow.’

This echoes the troubling notion of current citizen-on-citizen immigration checks, as enforced by the Immigration Acts of 2014 and 2016, with midwives now asking women about their immigration status at booking. Describing a midwife's need to ‘work with them regardless’ (Gaudion and Allotey, 2008) suggests that the midwife may feel unwilling to care for someone with an uncertain immigration status. This exposes preconceptions that a midwife may hold regarding who is or is not deserving of NHS care. The asylum-seeking women on the receiving end of this ‘caring relationship’ could face multiple disadvantages.

Stereotypes are present in all of an individual's actions, judgements and behaviour, even if they do not consciously agree with them (Abrams, 2010). Individuals who are sensitive to differences in status between social groups may try to sustain a positive in-group identity. Out-group members (those who are perceived to be different) may pose an ascertained cultural or economic threat to the social majority's position of power (Abrams, 2010).

It has been suggested that people working in stressful environments who are required to make decisions quickly are more likely to rely on implicit bias towards out-groups (Muoni, 2012; Stepanikova, 2012). The time pressures, noise and inadequate staffing of a maternity ward may increase the need for quick decision-making (Ford and Kruglanski, 1995; Kruglanski et al, 2006), thereby resulting in intense pressure on midwives that could lead to an exacerbation of subconscious discriminatory attitudes.

It is critical to consider how stereotypes are created. Midwives are subject to media and political news discourse that often uses collective pronouns, such as ‘us’ and ‘them’, which may fuel the public perception of asylum seekers as ‘other’ (Kirkwood et al, 2013). One way in which the media alienates asylum seekers is through the use of water-based metaphors, with examples including a ‘first wave’ (Drury, 2015) of people or a ‘flood’ (Brown, 2015) or ‘surge’ (Drury, 2016) of migrants. This encourages the reader to perceive asylum seekers as objects of force, rather than people. Depersonalisation discourages the reader from experiencing empathy and compassion towards the objectified (Pruitt, 2019).

Statements in academic papers such as ‘the child in utero of an immigrant is a future UK citizen, and optimising maternity care is a dimension of securing the future health of the nation’ (Higginbottom et al, 2019) perpetuate the idea that care is only important and valid when it is given to one of ‘us’ (a future UK citizen). The pregnant woman is not granted value, and the justification to provide care is for the good of a future member of UK society. The ‘othering’ of asylum-seeking individuals will undoubtedly impact how professionals care for these women, even at a very subconscious level.

The UK's political stance towards asylum seekers may directly impact people's perceptions. The Home Office is currently enforcing a ‘hostile environment’ policy as a means of discouraging people from entering and remaining in the UK and preventing irregular migrants from accessing everyday essentials (Yeo, 2018). It is understandable that midwives may align their beliefs with the UK press, particularly when political parties falsely claim that addressing immigration issues would secure significantly more funding for the NHS (Reid, 2019).

Structural difficulties

The reviewed papers illustrated how midwives are underresourced, understaffed and facing increasing pressure at work (Gaudion and Allotey, 2008; Bennett and Scammell, 2014; Tobin and Murphy-Lawless, 2014; Cross-Sudworth et al, 2015). This negatively impacts their ability to provide adequate care.

Translation services

In the majority of papers, a language barrier was seen as a significant barrier to providing adequate care (Gaudion and Allotey, 2008; Harper-Bulman and McCourt, 2010; Kurth et al, 2010; Bennett and Scammell, 2014; Tobin and Murphy-Lawless, 2014; Cross-Sudworth et al, 2015). However, on deeper analysis, the challenge was not the language barrier itself but the ability to use translation services.

The impact of the language barrier on a healthcare professional was given great emphasis, with midwives expressing ‘frustration at the increased time and perceived extra workload this caused them’ (Tobin and Murphy-Lawless, 2014). Using an interpreter was often a last resort.

‘We look to see whether there is anyone who works in the hospital who knows this particular language.’

‘The interpreting policy is to try and find a member of staff first; this may not be just within maternity services … it could be anyone—someone from the lab, for example.’

‘Due to amounts of applications, [we are] now informed not to book interpreters—[it is] too costly for GPs.’

A reluctance to use translation services for asylum-seeking women in maternity services is a common research finding that is not isolated to this systematic review (Asif et al, 2015; Haith-Cooper and McCarthy, 2015; Feldman, 2016; Higginbottom et al, 2019; McKnight et al, 2019; Fair et al, 2020). This is an example of the multiple marginalisations that women seeking asylum must face. Interestingly, there is little academic literature regarding the structural causes underlying the underuse of translation services.

The NHS is facing financial difficulties, and translation services are costly for local clinical commissioning groups (Robertson et al, 2017). The CEO of 2020 Health (2012) was quoted by the BBC at the time saying ‘urgent action must be taken by trusts to stem the flow of translation costs’ (BBC News, 2012). The water metaphor used by the media is echoed here in public policy, implying that the system is almost uncontrollably haemorrhaging money on services for those unable to speak English.

Hospitals are under fiscal pressure to limit and carefully prioritise spending on all aspects of care. This imposes the need for frugality on staff, who are urged to play their part. When reflecting on why translation services are so underfunded, it is interesting to consider the racial and ethnic identities of those in positions of power who are responsible for funding decisions. Racially and ethnically diverse populations are grossly underrepresented in managerial positions within the NHS (NHS England, 2020). These populations are more likely to have limited English fluency or to have family whose English fluency is limited (Gov.uk, 2018). Some managers without such lived experience may have less empathy or consideration for the need for translation services.

Among some professionals, there is a belief that the ‘right’ to live in the UK is balanced against certain obligations, such as the ‘right’ to receive healthcare being balanced against the duty to learn English (Adams, 2007). This perception does not consider the psychological and structural difficulties that influence an individual's ability to learn English (Salvo, 2017), as well as the dramatic funding cuts imposed on English language education services for asylum seekers over the last 10 years (Refugee Action, 2019). It is interesting to consider the potential implications of NHS managers being predominately white British and what the resulting inequality of care provision might be in regards to budgeting for translation or language education services.

Being overworked

The review highlighted that midwives were often overworked. Asylum-seeking women had complex additional needs, which required more of the midwife's time (Gaudion and Allotey, 2008; Haith-Cooper and Bradshaw, 2013b; Bennett and Scammell, 2014; Cross-Sudworth et al, 2015). Midwives felt ‘rushed’ and lacked ‘time to deal with complex issues’ (Cross-Sudworth et al, 2015). They appreciated the need for more time, to ‘enable a more thorough and satisfying consultation for woman and midwife’ (Cross-Sudworth et al, 2015).

‘[Asylum seekers] can double appointment time with language problems, but [there is] no extra time allocated.’

‘[The midwives] are going to have to get interpreters and that's going to take a long time and, because it does, it doubles the time that [they] spend with a woman, which I think puts stress on members of staff … but, you know, it has to be done, that's the job.’

Midwives were not allocated time to provide additional care. Some midwives avoiding expressing interest in care for asylum-seeking populations in case they ‘became known as the one who knows and ended up carrying the burden’ (Gaudion and Allotey, 2008). Overall, there were frequent mentions of excessive workload, with ‘escalating demand for services in excess of the ability for staff to keep pace’ (Gaudion and Allotey, 2008). Midwives were reluctant to ask about issues such as domestic violence because they would then be expected to ‘have the time to listen’ and because they ‘may have to do something’ (Gaudion and Allotey, 2008).

The findings of this review are supported by literature detailing the extreme pressures facing midwives (Pezaro et al, 2016). Maternity services are described as ‘running on goodwill’, reliant on midwives working through their breaks and well beyond their expected hours to provide safe care for women (RCM, 2016a). The staffing pressures and workload demands facing midwives on a routine shift mean the additional needs of an asylum-seeking woman can tip the balance:

‘Women who presented in labour or with complications and were not registered for care at the hospital were a particular source of concern and frustration.’

Tobin and Murphy-Lawless, 2014

The social circumstances of asylum-seeking women added to the workload of midwives and created logistical problems within the maternity unit, such as bed blocking.

‘Asylum seekers present a particular challenge because they have nowhere to live or clothes for the baby, and they effectively block a bed, which is costly and a poor use of services.’

Some midwives were ‘generally exhausted and frustrated with the role expanding into social care’ (Cross-Sudworth et al, 2015) and felt that this aspect of care was not their role. It was not possible to allocate the time to negotiate additional social care plans.

‘A senior midwife explained that there just wasn't time to ring around the community when there were more pressing clinical issues that required attention.’

Physical fatigue contributes to compassion fatigue, in which one is exposed to the suffering of others to such an extent that they develop an inability to empathise or feel compassion (Reed, 2021). Burnout is characterised by emotional exhaustion, depersonalisation and undermined personal achievement (Maslach and Jackson, 1981). Midwives who are burnt out can experience emotional detachment from women and become increasingly cynical. As a result, patient care is negatively impacted (Kinman et al, 2020). This emotional detachment and cynicism can be seen in the interviews with midwives included in this systematic review. To conclude that midwives can simply be racist and unkind is reductionist of the broader picture in which a midwife is trying to provide care. When staffing is poor and midwives are burnt out, it is easy to see how standards of care may slip. The psychological need to make decisions quickly means that midwives may rely upon unconscious biases when making decisions if they are fatigued. It is plausible that patients who do not pose a threat of litigation, such as asylum seekers, may become less of a priority.

Systematic failings

Lack of knowledge

Many midwives lacked an understanding of how the asylum system worked and were not confident with issues of asylum (Kurth et al, 2010; Haith-Cooper and Bradshaw, 2013a, b; Bennett and Scammell, 2014; Tobin and Murphy-Lawless, 2014). This literature review highlighted a lack of education and training for midwives who were caring for asylum seekers and the related care pathways.

Student midwives had very little knowledge of asylum seekers’ entitlement to services and were shocked when they learnt how little it was.

‘How are they supposed to support them, family and a child with that amount of money?’

Haith-Cooper and Bradshaw, 2013a

In addition, there was an apathetic attitude demonstrated surrounding cultural awareness and knowledge, in which it was assumed that a midwife could never fully understand all cultural backgrounds, with the expectation that one ‘learns on the job’.

‘You can't know the cultures of everybody. She's [the woman seeking asylum] arrived from Sudan, [but] could be somebody from somewhere completely different. You learn as you go along, I think.’

Haith-Cooper and Bradshaw, 2013a

Many midwives ‘expressed [the] need for the wider multi-disciplinary team to have access to training’ (Bennett and Scammell, 2014). There was broad uncertainty regarding the asylum trajectory.

‘People brought in by immigration services from the airport.[are] dismissed as health tourists’

A lack of ability to differentiate between immigration categories was not uncommon (Gaudion and Allotey, 2008; Haith-Cooper and Bradshaw, 2013a, b), with multiple examples in the literature of midwives lacking awareness of the reasons for asylum.

‘What are they doing here?’

Tobin and Murphy-Lawless, 2014

Poor knowledge led to a lack of confidence.

‘I am quite overwhelmed at times as to how complex these ladies’ lives are and how much input they need, and how many different organisations are needed to meet their various needs.’

The lack of training and institutional support contributed to ‘feelings of powerlessness on the part of the midwives themselves’ (Tobin and Murphy-Lawless, 2014), relating to the theme of midwives feeling exploited and overwhelmed. This was exacerbated by hospital trusts, which were ‘unsupportive and take the view of “just get in and do the job’” (Cross-Sudworth et al, 2015).

Structurally, this is a failing of the education system in which midwives are trained and updated during their career. Asylum-seeking women may face additional disadvantages when they are cared for by professionals who have limited knowledge regarding their needs.

The stress of caring

Some health professionals were overwhelmed by the complex issues facing asylum-seeking women.

‘Many were unprepared for the impact that working with traumatised women would have on them.’

Tobin and Murphy-Lawless, 2014

In some regards, this had a positive impact. It increased empathy and compassion for the women and ‘helped midwives to see the women as real people with real lives, and as women just like them’ (Tobin and Murphy-Lawless, 2014). However, for some midwives, the emotional challenges were difficult.

‘The midwives did not have anywhere to take their pain.’

Tobin and Murphy-Lawless, 2014

This is not an issue that is unique to the care of asylum-seeking women. Midwives often suffer vicarious trauma as a result of their experiences at work and do not have the necessary support systems to debrief and manage these emotional difficulties (RCM, 2016a).

Limitations

This review is limited by its scope. A relatively small number of midwives’ views are represented by the literature selected; therefore, the findings cannot be used to generalise about the attitudes and experiences of all midwives.

In addition, this systematic review considered the issues affecting asylum seekers as a broad, homogenous group. Future work on specific groups of asylum seekers, such as those on the Syrian, Afghan or Ukrainian resettlement schemes, would add greater insight into the specific attitudes of midwives towards people seeking asylum from particular regions.

Key points

- The midwives whose experiences are represented by this review lacked the time to provide adequate care for women seeking asylum.

- Some midwives held racist and stereotypical views towards women seeking asylum.

- Asylum-seeking women are at higher risk of maternal morbidity and mortality. More research is needed into their relationship with midwives and how this influences care outcomes.

CPD reflective questions

- To what extent is the midwifery staffing crisis responsible for poor outcomes among vulnerable women?

- How can maternity services be better designed to meet the needs of asylum-seeking women?

- How does media messaging and the influence of political policy influence the way midwives engage with women seeking asylum?

Conclusions

This systematic review explored health professionals’ perceptions and experiences providing maternity care for asylum-seeking women. Eight papers were systematically reviewed and three key themes were found. To the best of the authors’ knowledge, this systematic review is the only piece of work addressing this issue.

Although the papers reviewed were generally of limited quality, there were some key messages. Midwives lack the time to care appropriately for asylum-seeking women. A lack of time and resources may negatively impact midwives’ attitudes towards asylum-seeking women. Additionally, stereotypical perceptions are held by every individual and can be reinforced by media and political discourse. In order to be truly self-reflective of one's own personal bias, individuals need time and support to critically appraise their own beliefs.

There is significantly more research to be conducted in this area. As part of the welcome shift towards a maternity service that is more culturally aware, it is critical to reflect upon the racial and political context in which care is provided. It appears that maternity services in the UK are not designed and arranged to provide adequate care for asylum-seeking women, who face disparities in maternity outcomes. Midwives are grossly overworked and may be unable to provide an adequate standard of care for this demographic. For the system to improve, midwives need to be allocated more time not only to care for asylum-seeking women, but also, crucially, to enable them to reflect upon their own personal bias.