Induction of labour is a relatively common procedure worldwide, which is used for approximately 20% of pregnancies (NICE 2008). For over 50 years, prostaglandins have been the pharmaceutical method of choice to stimulate labour (Ayaz et al, 2013). Prostaglandins are used to artificially ripen the cervix, thus increasing the chance of labour occurring (Kalkat et al, 2008). The Propess® (a slow-release pessary) method of induction involves a pessary being inserted for 24 hours with the Prostin vaginal gel induction, involves 6 hourly administrations with repeat doses as required and directed by the induction of labour clinical guideline (NICE, 2008). Approximately two thirds of inductions will only require prostaglandins with no further interventions. There is no specific discussion of oxytocin usage following induction in this guideline or other international guidance documents. Following induction of labour, 15% will have an instrumental delivery with around 22% requiring a caesarean section (NICE, 2008). None of the national clinical guidelines report oxytocin augmentation rates specific to different preparations and doses of prostaglandins.

The Challenge

In May 2015, there was a European shortage of dinoprostone 1mg gel (Prostin) with no stock available locally from the end of June. Prior to May 2015, induction of labour with dinoprostone gel was the norm in Ireland with dinoprostone 10mg pessary (Propess®) used only occasionally in some Dublin maternity units, despite its routine use in the UK for several years. In the absence of the 1mg gel preparation and an unfavourable cervix, the only alternative would be to perform an elective caesarean section (CS). The induction rate locally was 30% so the CS method was not a valid option from a woman's choice perspective, especially considering mortality and morbidity risks posed when there were other options available to induce labour. Following an emergency Directorate meeting, the dinoprostone 10mg (Propess®) pessary was identified as an alternative method to induce labour and therefore sourced for use. A Dublin hospital, which used Propess® for induction of labour occasionally, shared its guideline. This was adapted locally and the use of Propess® for induction of labour was implemented into practice in June 2015.

After the first month of using Propess®, it was verbally noted within the unit that the induction process appeared to take longer with the Propess® pessary than with Prostin. However, it was also perceived that there were more vaginal deliveries using the Propess®. As a result of these beliefs, it was decided to conduct an audit to compare these two methods of induction.

Aims

To audit dinoprostone inductions, the criteria standard in the National Institute for Health Care Excellence (NICE) Clinical Guideline 70 Induction of Labour (2008) was used which recommends research into the effectiveness and safety of different dinoprostone regimes. This was identified as the overall aim of the audit. The guideline recommends two means of inducing labour. Method One involves Prostin gel being administered 6 hours apart with a maximum of 2 doses in 24 hours. Method Two uses one pessary in 24 hours i.e. Propess®. If after 24 hours labour has not been achieved, a further attempt at inducing labour may be undertaken or a caesarean section is performed (NICE, 2008).

Objectives of the audit

Methodology

To perform this audit, an overview of the literature was undertaken. This identified several studies which had been carried out previously, from which audit tools had been devised, tested and validated to collect the information. This tool was brought to the Directorate for approval by the midwifery manager, who identified the need to audit this new local practice. A consultant obstetrician agreed to be the clinical lead with an obstetric registrar and obstetric senior house officer assisting with the data collection. A pilot of three charts was performed. Approval from the hospital clinical audit team was sought and granted.

A retrospective analysis of the pregnancy records of all inductions of labour locally, comparing the use of dinoprostone gel (Prostin) versus dinoprostone slow release pessary (Propess®), was undertaken. Inclusion criteria meant women had to be at a minimum of 37 weeks' gestation, with a cephalic presentation, singleton pregnancy, requiring induction involving the administration of dinoprostone. No women who had previous caesarean sections or uterine scars were included in the audit.

A systematic review of the case notes from May 2015 to October 2015 was performed to obtain the information. A total of 70 women met the criteria and all were included in the review. This was to facilitate a snapshot overview of the local practice. By including all of these inductions, the auditors believed it would reduce bias. During this time frame, 30 women were induced using Propess® and 40 using Prostin.

Limitations

This was a retrospective study with no randomisation to the different groups so like with like was not controlled in order to perform a true assessment. The audit was performed over a six-month period so only involved the women induced during these dates. This could limit the data and if another six months had been audited, different results may have been obtained. However, as this audit was undertaken to obtain baseline data relevant to this new method of inducing labour locally, different dates to compare findings were not available. The hospital computerised system used to identify the inductions of labour during the time period is dependent on the midwives entering correct data about whether the labour was spontaneous or induced so some inductions of labour may not have been captured during the audit.

Results

A total of 70 medical records were audited by the audit team. The audit pro forma was completed for each chart with 40 women being induced using Prostin gel and 30 being induced using Propess®. The clinical audit support team input the data and generated results. These results were then analysed and reported by the midwifery manager on the audit team.

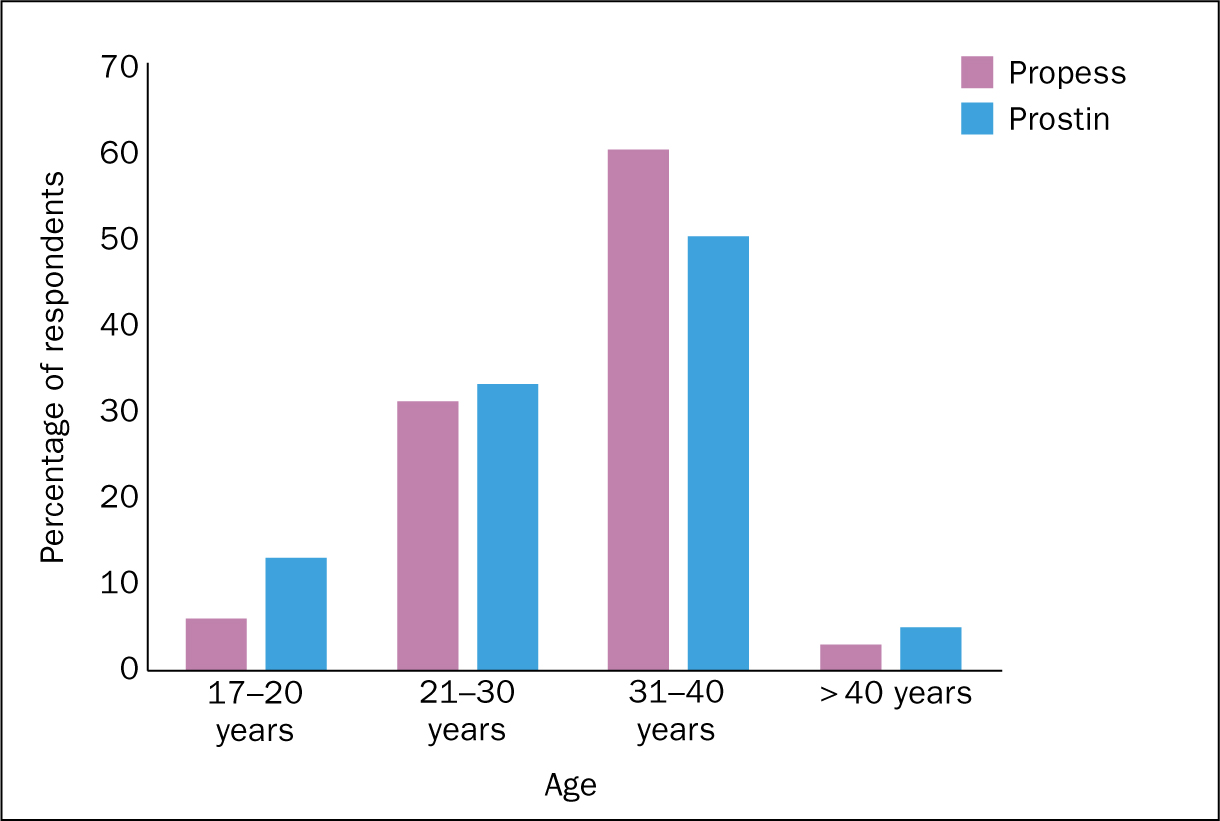

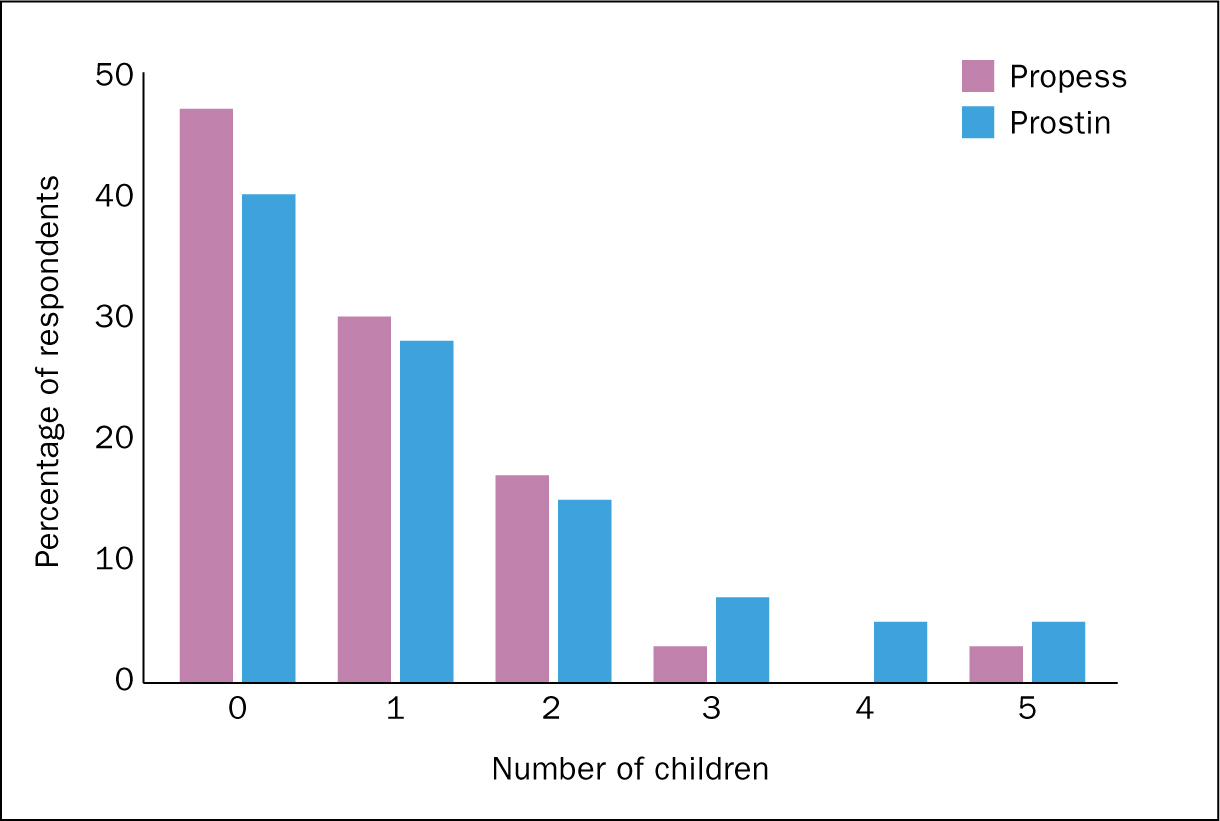

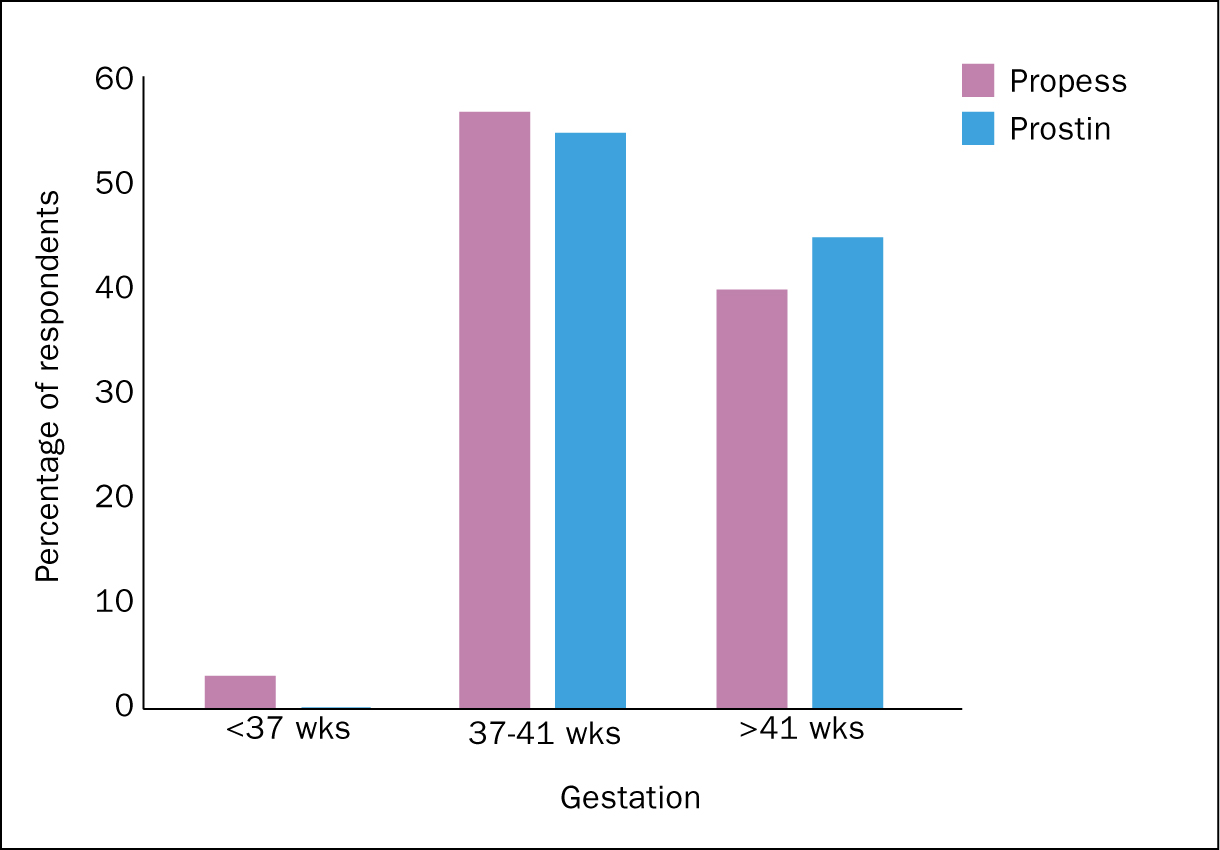

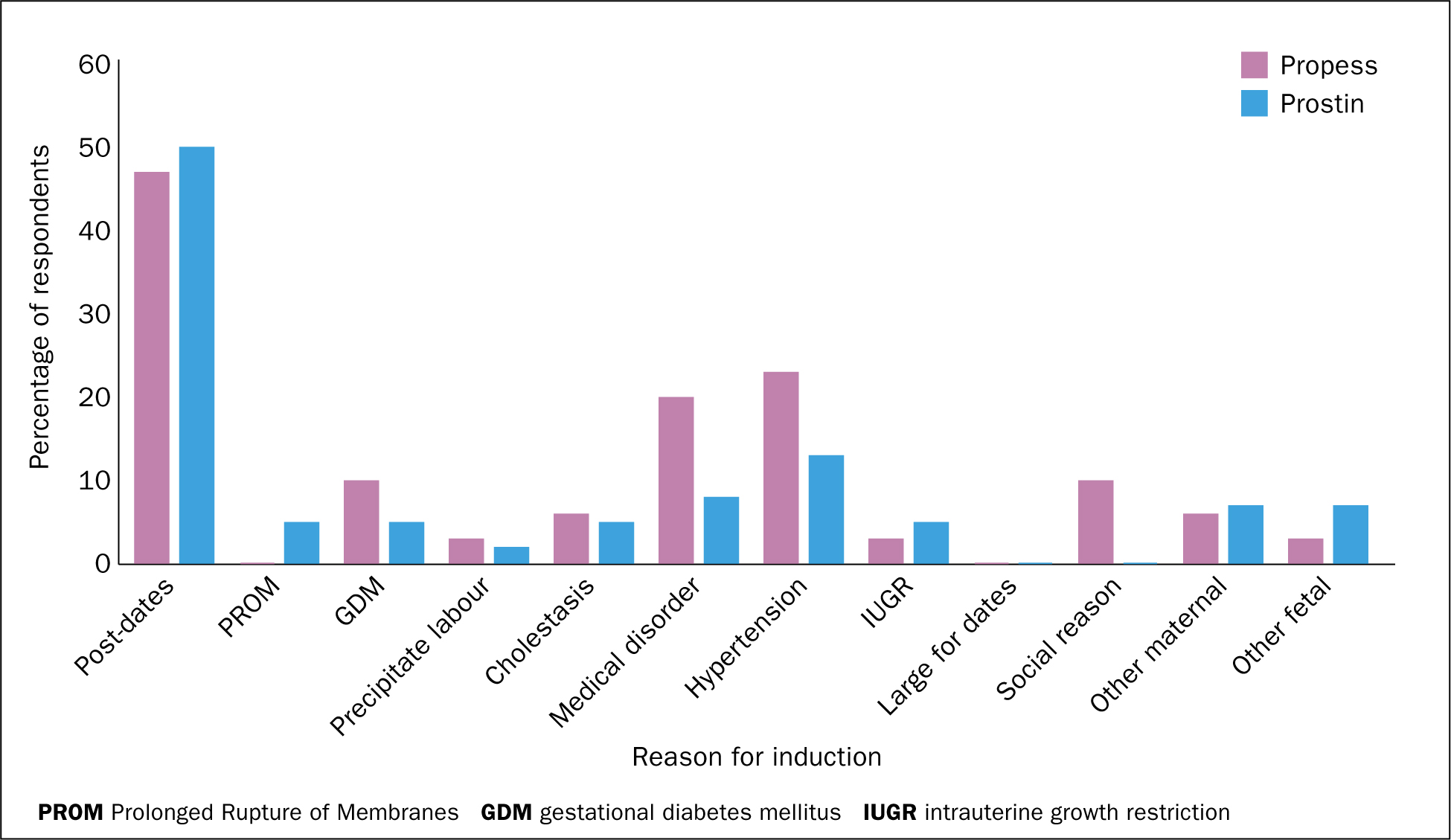

Patient demographics

Age, parity and gestation were identified as being similar between the Propess® and the Prostin group. The reason for being induced was comparable between the two groups and also similar to international studies (Kalkat et al, 2008; Tirlapur et al, 2010; Ayaz et al, 2013; Leduc et al ,2013; Malik et al, 2013 and Chen et al, 2014). As a result, it was felt by the team that comparison between the two groups would prove not only useful locally but could be benchmarked against other studies (Figure 1 and Figure 2).

There were a 7% higher number of primigravidae in the Propess® group which may affect the overall results. Some could have been excluded to ensure both groups had similar numbers. However, to reduce bias and to comply with the inclusion criteria, none of these were excluded from the audit (Figure 3 and Figure 4).

Medical disorders included all medical issues except hypertension. Hypertensive disorders were separated from the medical disorder category in order to capture rates of induction for preexisting hypertension, pregnancy induced hypertension and pre-eclampsia. Both of these groups accounted for approximately a quarter of induction reasons.

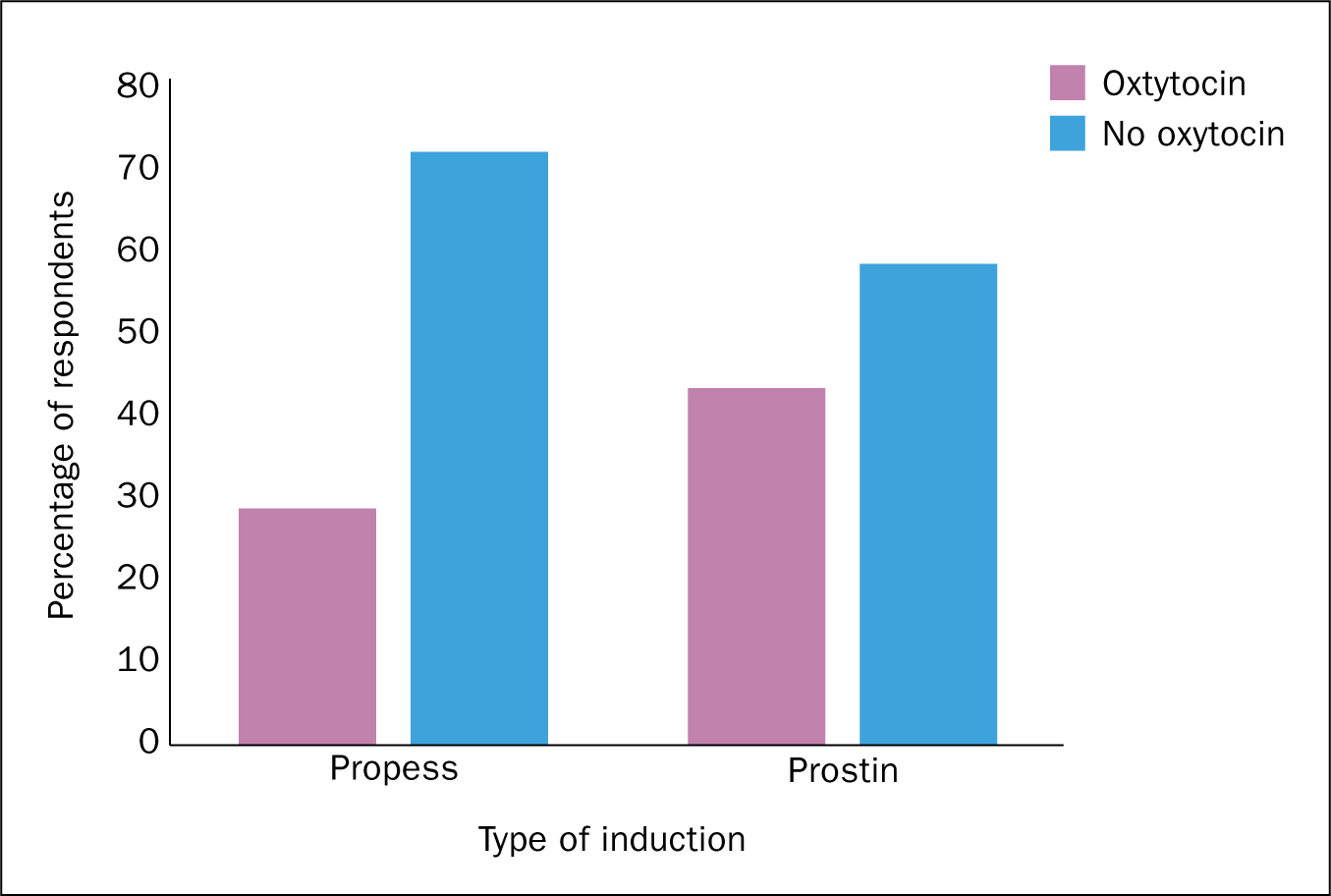

Augmentation following induction of labour

Following the administration of dinoprostone, 70% of the Propess® group had their labour augmented with an artificial rupture of membranes. The oxytocin augmentation rate for the Propess® group was 28.5%, with 71.5% of this group, establishing labour (Figure 5). Oxytocin use requires continuous fetal monitoring leading to reduced mobility for the woman and may result in overall dissatisfaction of the birthing experience. Oxytocin may also stimulate intense contractions with a risk of uterine hyper stimulation, fetal hypoxia and fetal distress (El-Shawarby and Connell, 2006).

Of the Prostin group, 35% of the Prostin inductions needed more than one cycle of the gel, with 14% requiring 3 or more doses. There was a 60% artificial rupture of membrane rate with 43% of the Prostin group requiring oxytocin augmentation of their labour.

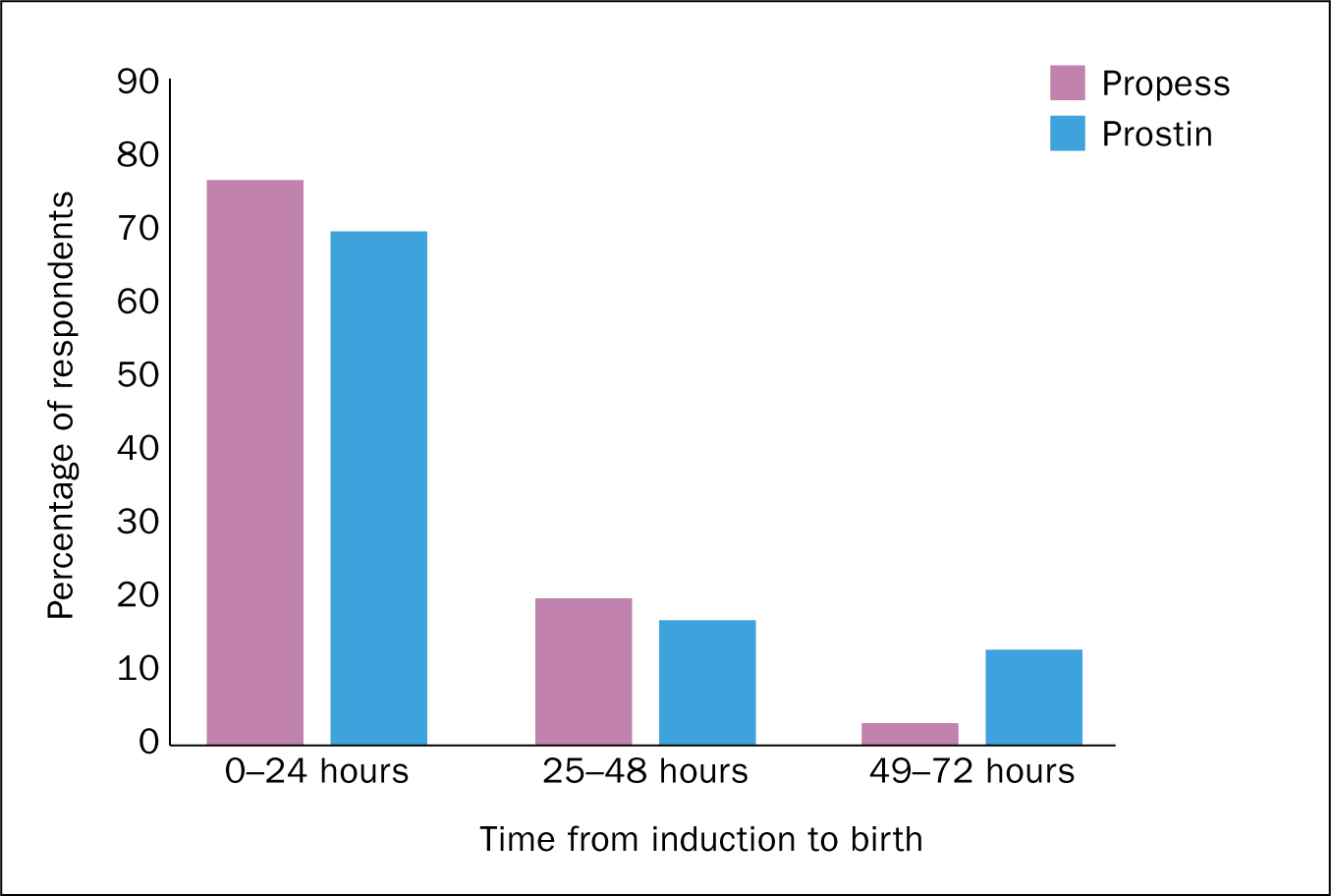

Induction to time of birth interval

Following the administration of dinoprostone, 19 women had a labour which exceeded 24 hours. This was composed of 23% in the Propess® group and 30% in the Prostin group (Figure 6).

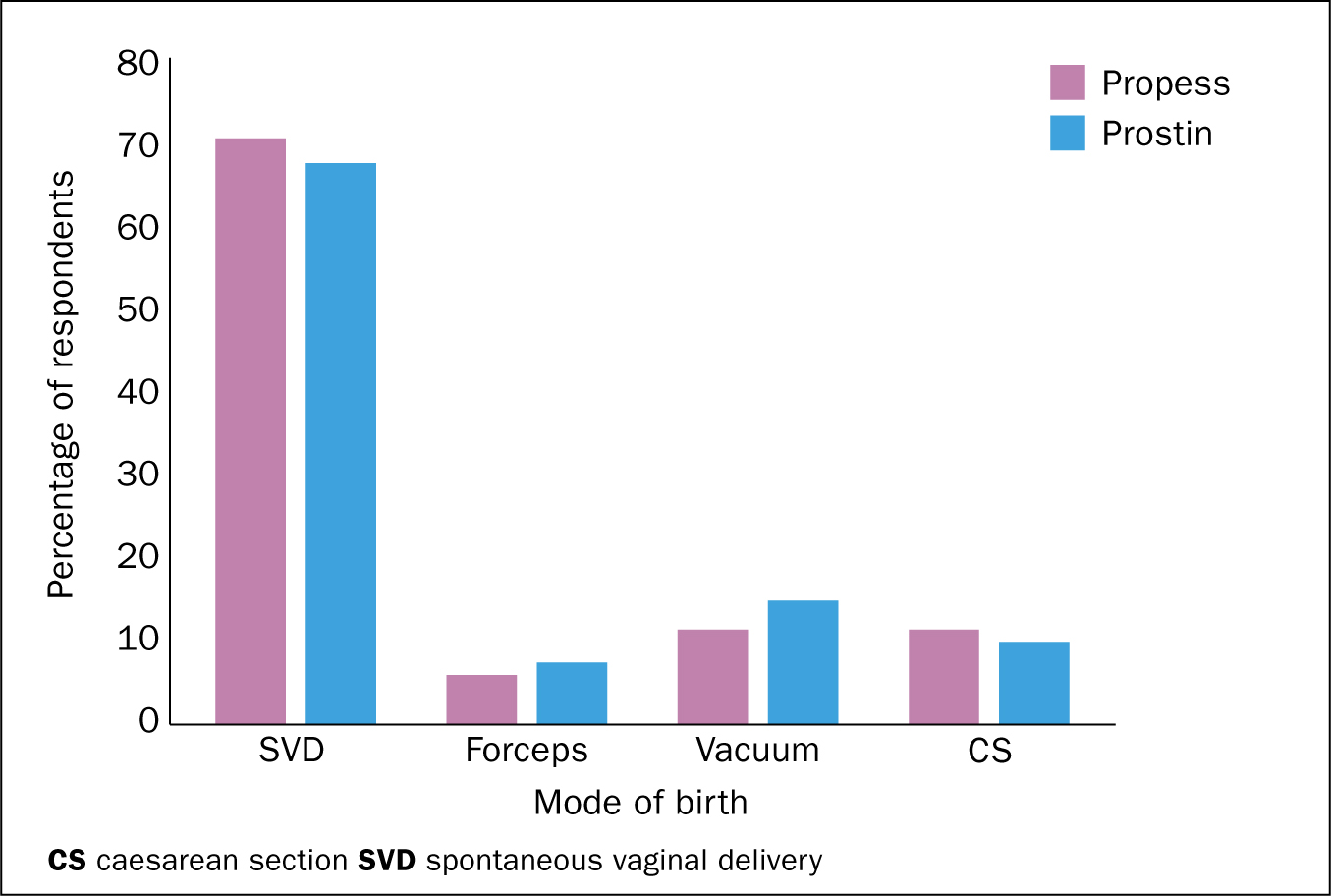

Mode of birth

The Propess® group had an 88.5% vaginal birth rate with 71% of these being spontaneous and 17.5% being instrumental. There was an 11.5% caesarean section rate for the Propess® group — 4% of this group needed Prostin gel as well. All of them had vaginal births. These women were excluded from the audit results (Figure 7).

The Prostin group had a 90% vaginal birth rate with 68% of these being spontaneous and 22% being instrumental. There was a 10% caesarean section rate for the Prostin group.

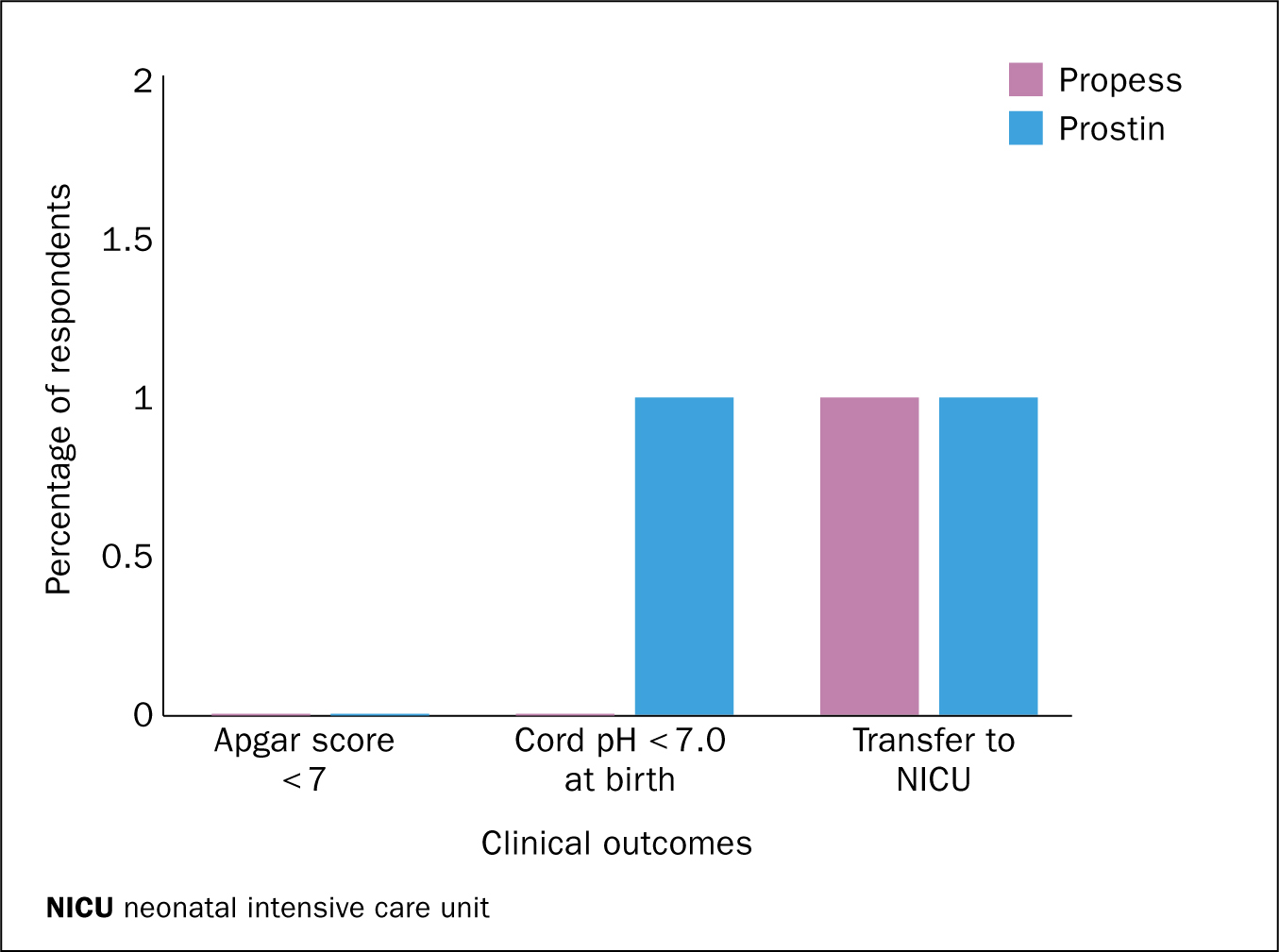

Clinical outcomes following induction

There were no notable differences in the dinoprostone groups based on clinical outcomes of babies (Figure 8).

Discussion

Augmentation following induction of labour

The local findings of 28.5% of the Propess® group requiring oxytocin augmentation is comparable to the findings of Kalkat et al (2008), where a significantly lower oxytocin augmentation rate with Propess® was noted. This local finding was significantly lower than Malik et al (2013) findings of a 54% oxytocin augmentation rate following induction. By reducing the use of oxytocin, the risk of hyper stimulation of the uterus, fetal distress and birth asphyxia as well as uterine rupture complications are reduced (WHO 2014). Oxytocin usage also requires close monitoring with one to one care cited as best practice (WHO 2014), therefore having staff costing implications. It also hinders the woman's mobility, intensifies contractions and can result in frustration and reports of dissatisfaction with the overall birthing experience (El-Shawarby and Connell 2006).

Induction to time of birth interval

Locally, 77% of the women birthed in less than 24 hours with 20% taking over 24 hours but less than 48 hours with 3% birthing between 48 and 72 hours following the administration of Propess®. Kalkat et al (2008) found that 63% of their Propess® group birthed in less than 24 hours. Tirlapur et al (2010) found that their Propess® group took up to 88 hours to birth, whilst Malik et al (2013) found their women birthed within 48 hours of Propess® administration. Chen et al (2014) identified a shorter induction to birth time with Propess® inductions.

Locally, 70% of the women birthed within 24 hours, with 17% taking 24-48 hours and 13% birthing between 48 and 72 hours following the administration of Prostin. Kalkat et al (2008) found that 67% of their Prostin group birthed within 24 hours whilst Tirlapur et al (2010) also discovered that the majority of their Prostin women delivered within 24 hours.

The Propess® finding was interesting, as the staff locally had believed that the women took longer than 24 hours to birth if induced with Propess®. If this had been demonstrated, it would have been used as a reason to discontinue Propess® inductions. Instead it was shown that the Prostin group had a longer induction to birth time interval. None of the studies found similar induction to time of birth intervals. This could be due to local practices or may simply be down to human nature and variations in labour times where findings could never be replicated due to the different study population.

Mode of Birth

Locally the Propess® group had a 71% spontaneous birth rate and an overall vaginal birth rate of 88.5%, with Prostin inductions resulting in a 68% spontaneous birth rate and an overall vaginal birth rate of 90%. Kalkat et al (2008) compared Propess® and Prostin inductions. They found that the number of vaginal births by 24 hours was similar. However, they noted that the Propess® group took longer to establish in labour but had a lower oxytocin augmentation rate (Kalkat et al, 2008). These findings, especially the lower oxytocin use, were replicated in this audit.

Locally the caesarean section (CS) rate was 11.5% for women who were induced using Process® and 10% in those induced with Prostin. Tekin et al (2015) showed that Propess® reduced this rate even though it took longer to establish into labour.

Clinical Outcomes

Kalkat et al (2008) found no difference in neonatal outcomes between Propess® and Prostin. These findings were also demonstrated locally with one baby from each group being admitted unexpectedly to NICU. No babies had Apgar's less than seven at birth with one baby from the Prostin group having a cord pH less than seven at birth.

Conclusions

The figure of 88.5% for vaginal births in the Propess® group along with the low augmentation figures of 28.5% would indicate that this is a safe, reliable method of induction. It could have the potential to not only reduce CS rates but also decrease the morbidity and risks associated with oxytocin use. This safe and cost-effective finding was also identified by Malik et al (2013).

Prostin was found to be safe, reliable and cost effective with 90% having a vaginal birth. However, repeat doses were required and 43% needed augmented labour.

From the audit findings there needs to be consideration on the use of Propess® for all inductions. This is not just as a cost-effective method of induction resulting in a high vaginal birth rate. It is also secondary to the reduction in oxytocin augmentation and the extra monitoring and care in labour and potential problems that arise from its use.

There is a need to further audit induction of labour in 2017 to compare findings with the 2015 audit and to include client experience as well.

Implications for practice

Half way through the audit, Prostin 1mg became available again from the supplier. Other units within the hospital group, had not experienced the interruption in supply so the local unit was the only one using Propess®. A directive was received from the hospital group to cease the use of Propess® locally. However, due to the preliminary audit findings, its continued use was permitted. Following the completion of the audit and the dissemination of the findings to the group, one other unit has commenced using Propess® with two other units currently adapting the local guideline in order to introduce it into their units as a means to induce labour.