Numerous policy documents from the Department of Health (2009a; 2009b; 2011; 2012a; 2012b; 2013) recognise that breastfeeding is associated with overwhelming health benefits and large potential cost savings. It has been identified as a national priority and a key area of focus for the NHS and local partners. UNICEF UK published a report in 2012 stating that, if the number of babies in the UK receiving any breast milk at all rose by just 1%, this alone could potentially reduce 10 000 hospital admissions annually for babies owing to gastroenteritis and respiratory illness, and save approximately £40 million a year for the NHS (Renfrew et al, 2012). It also stated that this could potentially lead to a small increase in IQ which, across the entire population, could result in gains of more than £278 million in economic productivity annually.

Despite this, breastfeeding rates in England and Wales remain lower than in many other European countries (NHS England, 2015). For the last few years, a significant amount of time, energy and resources has been devoted to increasing breastfeeding rates across the UK; however, the most recent statistics remain somewhat depressing. In July 2015, NHS England (2015) published its findings for Quarter 4 2014/15, which showed that prevalence rates of breastfeeding at 6–8 weeks were lower for the preceding year than they were in 2011/12 (43.8% vs 47.2%).

Reasons for low breastfeeding rates in the UK are complex; however, it is well documented that women who have a caesarean birth are less likely to breastfeed successfully (Pérez-Ríos et al, 2008; Zanardo et al, 2010; Prior et al, 2012) and in the UK caesarean sections now account for around 26% of all births (Health and Social Care Information Centre, 2015). It has also been shown that many women do not breastfeed for longer than a few days, especially if formula milk or additional drinks are introduced in the early days following birth (McAndrew et al, 2012).

‘Kangaroo care’ (skin-to-skin contact between mother and baby at birth) has been studied extensively for many years and has been shown to have a positive effect on many different health outcomes for both preterm and term babies (Conde-Agudelo et al, 2011; Moore et al, 2012). A Cochrane review (Moore et al, 2012) involving 34 studies and 2177 participants found that early skin-to-skin contact results in better breastfeeding outcomes, cardio-respiratory stability and decreased infant crying for term babies. Other studies have found benefits such as improved bonding between mother and baby (Ferber and Makhoul, 2004), maintenance of thermoregulation (Overfield et al, 2005) and blood glucose levels (Hewitt et al, 2005), and a reduction in stress levels in the baby following the birth (Ferber and Makhoul, 2004). The Baby Friendly Initiative developed by the World Health Organization and UNICEF (2012) recommends that all mothers should be encouraged to have immediate skin-to-skin contact with their babies at birth, until at least after the first feed and for as long as they wish afterwards.

Despite the evidence that early skin-to-skin contact can improve breastfeeding outcomes, it is generally not facilitated in the operating theatre. A Swedish study concluded that although midwives considered skin-to-skin contact to be important, they often experienced many obstacles in providing such care, such as lack of knowledge among parents and professionals and organisational difficulties such as collaboration with other professionals (Zwedberg et al, 2015). It is also important to note that although skin-to-skin contact is the gold standard recommended for all babies because of its benefits, there have been instances where healthy newborn babies have needed to be resuscitated because of apnoea or hypotonia while having skin-to-skin, and in some (very rare) cases, have even died (Pejovic and Herlenius, 2013). Although skin-to-skin contact after a caesarean section is still strongly recommended, caution is advised because of the increased risk of respiratory problems after birth (National Institute for Health and Care Excellence, 2011) and the prone position on the mother (Fleming, 2012). It is therefore vital this is performed with appropriate observation of the baby and correct positioning of the mother while in the operating theatre (Colson, 2014).

A recent review (Stevens et al, 2014) identified nine small studies that have investigated skin-to-skin contact immediately after caesarean section, or within 1 hour after birth, and the combined evidence of the review suggests that this may increase breastfeeding initiation and reduce formula supplementation in hospital. However, the studies included were small and the authors suggested more research was needed.

Local data for 500 women in the previous year who had a caesarean section and who initiated breastfeeding from birth, showed that 25% of women had already stopped breastfeeding or were introducing formula-feeding by 48 hours; however, there was only a further 4% reduction in breastfeeding by 10 days. This supports the finding reported in the Infant Feeding Survey 2010 (McAndrew et al, 2012) that the first 48 hours after birth is likely to be a crucial time for establishing breastfeeding, and has the potential to improve breastfeeding rates at later time periods, such as 10 days and possibly even 6 weeks.

Aim

The purpose of this study was to investigate the effects of immediate skin-to-skin contact in the operating theatre following caesarean birth on breastfeeding rates at 48 hours. The study follows on from a previous study investigating kangaroo care for preterm and small babies, performed at the same hospital, which found significant increases in breastfeeding rates (Gregson and Blacker, 2011).

Method

A randomised controlled study was set up to test the following null hypothesis:

‘There is no significant difference in breastfeeding rates at 48 hours when women perform skin-to-skin contact with their newborn baby in the operating theatre immediately after caesarean birth, when compared to normal care (skin-to-skin care performed after the operation)’.

Sample

The trial sample size was calculated using a joint statistical and pragmatic assessment, based on the number of women that could be recruited within an acceptable timescale and the size of the effect that could be measured. Sample size calculations were also influenced by findings of a prospective cohort study performed 2 years previously at the same hospital, which demonstrated a 17% increase in breastfeeding rates at 48 hours when women (irrespective of mode of delivery) were encouraged to perform as much skin-to-skin contact as possible in the first few days following birth. It was acknowledged that this group may have been especially motivated to breastfeed as the babies in this study were either premature (34–37 weeks' gestation) or rather small (<2nd centile for gestational age), therefore the final sample size was based on showing a 12% difference between the two groups for exclusive breastfeeding rates at 48 hours following delivery. With a 5% significance level and 80% power, it was estimated that 183 women per group would be required for the study, a total of 366 women.

Participants

The study took place at a district general hospital in south-east England between 25 February 2013 and 21 October 2014. Approval for the study was obtained from the local research ethics committee. All women having an elective caesarean section were eligible to be included in the study if they met the following criteria: singleton pregnancy at term (between 37 and 42 completed weeks of pregnancy), providing they wished to breastfeed their baby at birth. Exclusion criteria were women who expressed a wish to artificially feed their baby, women who had an unstable clinical condition at birth (e.g. massive postpartum haemorrhage), or if the baby was known to have a major congenital abnormality.

Eligible women were given an information leaflet and an opportunity to discuss the study at the routine pre-surgery assessment held approximately 1 week before surgery. On admission to hospital on the day of the surgery, those willing to participate in the study were asked to provide written consent.

Randomisation

After recruitment, participants were randomly allocated to one of two groups: immediate skin-to-skin contact in the operating theatre following birth, or delaying skin-to-skin contact until the operation was completed. The allocation of treatment was generated using a computer random schedule at the start of the study and assignment was concealed by placement in consecutively numbered, opaque, sealed envelopes drawn in consecutive order. The investigators were blind to allocation, but blinding of the participant and the midwife or nurse providing care was not possible due to the differences in treatment. Nulliparous and multiparous women were stratified to ensure equal numbers in each group as this was thought to be a factor that could potentially affect feeding outcomes.

Measures

The primary outcome was breastfeeding rates at 48 hours. Secondary outcomes were feeding methods at 10 days and 6 weeks following birth, admission to neonatal unit, length of time for which skin-to-skin contact was performed for the first episode after birth and during the first 24 hours, and women's experiences. The correlation of length of time for skin-to-skin with feeding outcomes was measured at 48 hours and at 6 weeks.

Intervention

Participants in the study group received a KangaWrap Kardi (a simple garment to help facilitate skin-to-skin) to wear underneath the operation gown, prior to admission to theatre. The garment had been designed and developed during the course of a previous study, to help women confined to bed (e.g. following a caesarean section) to perform skin-to-skin contact with their baby (Gregson and Blacker, 2011).

At birth, the baby was placed skin-to-skin prone on the mother's chest and the participant was encouraged to keep the baby skin-to-skin as much as possible during the first 48 hours.

Training sessions were held with staff in the operating theatre to ensure they were comfortable with tying the KangaWrap Kardi, positioning of the mother with one pillow during the operation and also to clarify that the midwife was responsible for observing the baby while in the operating theatre so that any deterioration in the baby's condition would be observed and acted on immediately.

Participants in the control arm of the study received ‘normal care’ as follows: following the birth the baby, it was placed in its mother's or father's arms and parents were encouraged to have at least 1 hour skin-to-skin contact. For ethical reasons, participants were then free to do as much skin-to-skin as desired, as it would not have been appropriate to terminate this after the usual period of 1 hour. For this reason the length of skin-to-skin contact time in the first 24 hours was measured to assess compliance with the control intervention.

All participants were asked to respond to a set of questions at 10 days to determine how well they were recovering from the caesarean birth, coping with their newborn baby and enjoying being a parent. They were asked to rate their answers on a Likert scale of four points: strongly disagree with the statement, disagree, agree or strongly agree. They were also asked for general comments around their experience.

Data collection

Data were collected from the participants' hospital records and patient questionnaires, and entered onto an Excel spreadsheet by the researchers.

Data analysis

The study group and control groups were compared for factors that could potentially affect feeding outcomes including parity, age, ethnicity, body mass index (BMI), gestational age, birth weight, presence of meconium and Apgar scores.

The experimental hypothesis was tested using statistical procedures available in SPSS for Windows. All tests were two-tailed with a significance level of P <0.05 accepted as statistically significant with 95% confidence intervals (two-tailed) presented alongside summary measures throughout. Parametric and nonparametric statistical tests were applied as appropriate.

The association between the skin-to-skin time in the first 24 hours and the feeding method at 48 hours was analysed by using Fisher's test. This method was preferred to the Chi-square test due to the small numbers in some categories. Owing to the small number of women in one of the skin-to-skin categories, the number of categories was reduced from four to three for the analyses.

Results

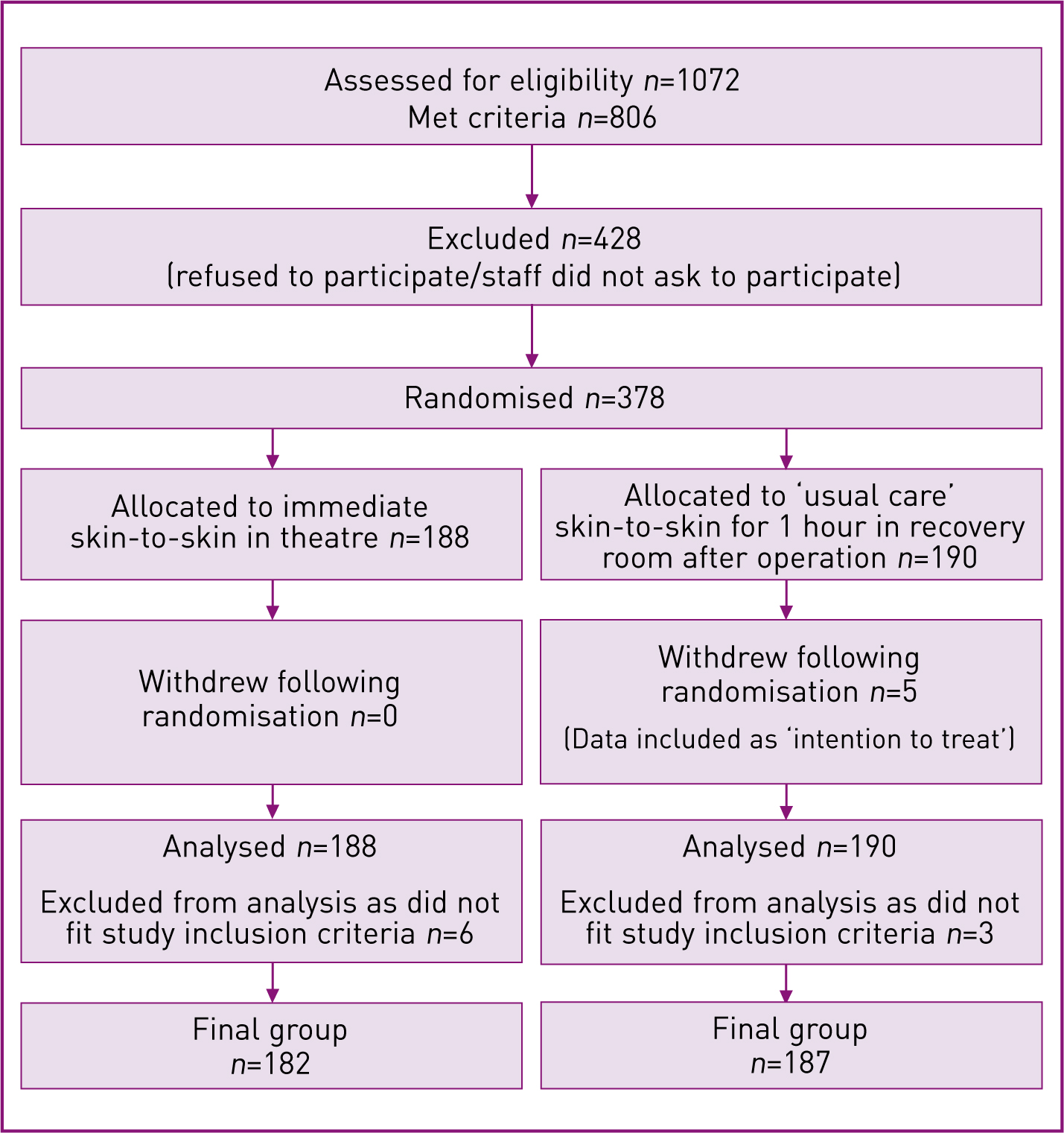

A total of 378 women were recruited, of whom 188 were allocated to the study group and 190 to control (Figure 1). Nine participants were excluded from analysis following randomisation (six from the study group and three from the control group) for the following reasons: one had a stillbirth, one baby was taken into care, one decided to bottle-feed, two sustained a major haemorrhage and subsequent intensive therapy unit admission, and four were of a gestational age less than 37 completed weeks of pregnancy and thus did not meet the criteria for entry to the study.

Five participants declared that they had ‘withdrawn from the study’ because they were not allocated to the study group; however, data for this group were available for most outcomes except length of time for first episode of skin-to-skin and for first 24 hours and particpants' experience, and were therefore included as ‘intention to treat’.

Maternal demographic details were compared across study and control groups, to ensure there were no significant differences between the groups that might affect results (Table 1). There were no important differences seen.

| Study group (n=182) | Control group (n=187) | |

|---|---|---|

| Parity | ||

| Nulliparous | 40 (22%) | 49 (26%) |

| Multiparous | 142 (78%) | 138 (74%) |

| Age | ||

| Mean (standard deviation) | 34.0 (4.9) | 33.2 (5.1) |

| BMI | ||

| Mean (standard deviation) | 25.4 (4.8) | 25.6 (5.3) |

| Gestational age (days) | ||

| Mean (standard deviation) | 275 (6) | 274 (6) |

| Sex | ||

| Boy | 96 (53%) | 91 (49%) |

| Girl | 86 (47%) | 96 (51%) |

| Birth weight (grams) | ||

| Mean (standard deviation) | 3469 (475) | 3469 (475) |

| Apgar score at 5 minutes | ||

| Median | 10 (9,10) | 10 (9,10) |

| Presence of meconium | ||

| No | 176 (97%) | 183 (98%) |

| Yes | 4 (2%) | 4 (2%) |

| Not recorded | 2 (1%) | |

Data for both groups were analysed for the primary outcome, which was breastfeeding rates at 48 hours after birth (Table 2). There was a 5% difference seen between groups for exclusive breastfeeding at this time; however, this was not statistically significant. There was also a 3% difference between groups for exclusive breastfeeding at 10 days, rising to 7% for 6-week figures; again, this was not statistically significant.

| Feeding method | Study group | Control group | P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Feeding at 48 hours | n=182 | n=187 | 0.25 |

| Breast | 161 (88%) | 156 (83%) | |

| Artificial | 8 (4%) | 8 (4%) | |

| Mixed | 13 (7%) | 23 (12%) | |

| Feeding at 10 days | n=182 | n=186 | 0.74 |

| Breast | 126 (69%) | 122 (66%) | |

| Artificial | 23 (13%) | 25 (13%) | |

| Mixed | 33 (18%) | 39 (21%) | |

| Feeding at 6 weeks | n=175 | n=181 | 0.44 |

| Breast | 93 (53%) | 84 (46%) | |

| Artificial | 49 (28%) | 57 (31%) | |

| Mixed | 33 (19%) | 40 (22%) |

There was no significant difference between groups regarding admission to the neonatal unit (Table 3). Two babies collapsed unexpectedly while having skin-to-skin contact following birth. One was noticed to be a poor colour around 10 minutes after birth and was immediately given intermittent positive pressure ventilations with a bag and mask, with no further problems. The second baby was noted to have stopped breathing on arrival at the postnatal ward. This baby was resuscitated, transferred to the neonatal intensive care unit and subsequently diagnosed with meningitis. The baby made a full recovery and was discharged home 10 days later.

| Study group n=182 | Control group n=187 | % difference 95% CI | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Neonatal admission | 8 (4%) | 4 (2%) | 2% (–1%, 6%) | 0.22 |

CI–confidence interval

Data relating to the length of time participants performed skin-to-skin contact with their baby immediately after birth and for the first 24 hours were available for 297 participants (144 study group and 153 control). This showed that 87% of the control group had performed skin-to-skin contact for more than 2 hours after birth, whereas they had been expected to do so for 1 hour or less. It also showed that similar numbers of the control group and study group had performed more than 4 hours of skin-to-skin contact in the first 24 hours (93% vs 94%) (Table 4). This suggested that a major ‘contamination’ of the control group had occurred; as a result, although there was a trend towards improved outcomes in the experimental group, this did not reach statistical significance.

| Study group | Control group | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Length of first episode of skin-to-skin | n=144 | n=153 | 0.12 |

| 30 minutes | 4 (3%) | 8 (5%) | |

| 1 hour | 12 (8%) | 13 (8%) | |

| 2 hours | 20 (14%) | 30 (20%) | |

| 3+ hours | 108 (75%) | 102 (67%) | |

| Skin-to-skin length of time in 24 hours | n=146 | n=152 | 0.34 |

| <4 hours | 11 (8%) | 11 (7%) | |

| 4–8 hours | 43 (29%) | 45 (30%) | |

| 8–12 hours | 42 (29%) | 59 (39%) | |

| >12 hours | 50 (34%) | 37 (24%) |

Following the observed ‘contamination’ of the control group, the data for both groups were combined and then tested to determine whether there was a correlation between the length of time skin-to-skin was performed and whether the baby was still receiving breast milk at 48 hours (Table 5). A longer skin-to-skin contact was associated with a significantly lower occurrence of artificial feeding at 48 hours and at 6 weeks.

| Skin-to-skin length of time in 24 hours | Breastfeeding/mixed feeding n (%) | Artificial feeding n (%) | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| All participants at 48 hours n=299 | <8 hours | 103 (94%) | 7 (6%) | 0.04 |

| 8–12 hours | 99 (97%) | 3 (3%) | ||

| >12 hours | 87 (100%) | 0 (0%) | ||

| All participants at 6 weeks n=293 | <8 hours | 62 (58%) | 45 (42%) | 0.003 |

| 8–12 hours | 36 (36%) | 63 (64%) | ||

| >12 hours | 49 (56%) | 38 (44%) |

Of participants who had performed more than 12 hours of skin-to-skin contact during the first 24 hours, 100% were still giving their baby breast milk at 48 hours. The correlation of time spent having skin-to-skin in the first 24 hours following birth and 6-week feeding data was not so consistent. Women with the least and most skin-to-skin time (< 8 hours and > 12 hours) had a higher rate of breastfeeding, with the occurrence lower in the middle 8–12-hour group.

At 10 days, participants were asked to respond to a set of statements to determine how they were coping with breastfeeding, how confident they were with performing skin-to-skin contact and how much they were enjoying being a parent. (Table 6). They were also asked to rate how well they were recovering from the caesarean birth and how settled the baby was. There was a trend towards a more favourable response in the study group for all the statements; however, statistical significance was only reached in the statement around how settled the baby was. A significantly higher number of participants in the study group felt that their baby was more settled than in the control group.

| Study group | Control group | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| It is easy to breastfeed after caesarean section | n=137 | n=154 | 0.08 |

| Disagree strongly | 20 (15%) | 30 (19%) | |

| Disagree | 24 (18%) | 25 (16%) | |

| Agree | 33 (24%) | 50 (32%) | |

| Agree strongly | 60 (44%) | 49 (32%) | |

| I feel confident and am enjoying performing skin-to-skin contact with my baby | n=140 | n=156 | 0.28 |

| Disagree strongly | 1 (1%) | 2 (1%) | |

| Disagree | 0 (0%) | 1 (1%) | |

| Agree | 17 (12%) | 24 (15%) | |

| Agree strongly | 122 (87%) | 129 (83%) | |

| I am recovering well from the operation | n=140 | n=156 | 0.50 |

| Disagree strongly | 3 (2%) | 2 (1%) | |

| Disagree | 3 (2%) | 5 (3%) | |

| Agree | 37 (26%) | 47 (30%) | |

| Agree strongly | 97 (69%) | 102 (65%) | |

| My baby is settled | n=141 | n=156 | 0.009 |

| Disagree strongly | 1 (1%) | 4 (3%) | |

| Disagree | 3 (2%) | 12 (8%) | |

| Agree | 50 (35%) | 64 (41%) | |

| Agree strongly | 87 (62%) | 76 (49%) | |

| I am enjoying being a new parent | n=141 | n=156 | 0.10 |

| Disagree strongly | 0 (0%) | 1 (1%) | |

| Disagree | 5 (4%) | 6 (4%) | |

| Agree | 27 (19%) | 42 (27%) | |

| Agree strongly | 109 (77%) | 107 (69%) |

Discussion

The main purpose of this study was to determine whether skin-to-skin contact in the operating theatre and afterwards would impact on breastfeeding rates at 48 hours. Although the difference seen was not of statistical significance, it could be argued that any such increase in breastfeeding rates is of immense clinical significance, especially in light of the UNICEF UK report stating that an increase as small as 1% would have such major benefits for the UK population and health economy (Renfrew et al, 2012). The increase in breastfeeding seen at 48 hours was also reflected in rates reported at 10 days and 6 weeks, when it rose further, to 7%. The increase seen would appear to be remarkable, especially considering that women who give birth by caesarean section are known to experience more problems with breastfeeding (Renfrew et al, 2012).

The major ‘contamination’ of the control group may also have had a significant impact on feeding outcomes, by reducing the differences seen between both groups. Results in Table 4 demonstrate that most participants in the control group performed much longer periods of skin-to-skin contact with their babies than expected. Usual care prior to the commencement of the study was for women to have around 1 hour of skin-to-skin with their baby in the recovery room and, anecdotally, it was often less than this—especially as staff placed a higher emphasis on recording of observations and rapid transfer to the postnatal ward once the woman's condition was stable. In this study, the data (where available) for all participants (study and control group combined) showed that 93% had skin-to-skin contact for more than 4 hours, and as many as 63% for more than 8 hours, which is likely to have been instrumental in reducing the difference in breastfeeding rates between study and control groups.

The correlation seen in this study between the length of time that skin-to-skin contact was performed in the first 24 hours and the baby still receiving breast milk at 48 hours, provides some evidence that the length of time that women perform skin-to-skin contact during this period may be an important factor for increasing breastfeeding rates. Although the correlation was not so consistent for the 6-week feeding outcomes, it would appear to merit further research.

Although the design of this study could be criticised for the contamination that occurred in the control group, it also demonstrates the power of a research project for effecting change, especially if participants perceive the intervention to be positive for their baby. Most of the participants were keen to perform skin-to-skin contact and virtually all the participants in the control group were disappointed not to be selected for the study group, hence their decision to perform as much skin-to-skin as possible anyway as soon as the operation was finished. Questions around participants' experience with skin-to-skin contact also identify that it was associated with a pleasant experience for the majority. The trend towards more positive answers in the study group indicates that the time in theatre immediately after the birth may be of particular importance for parents feeling that their baby was more settled 10 days after the birth.

In times of ongoing constraints on public spending, it is crucial that resources are focused on things that make a difference to women's breastfeeding outcomes. This study demonstrates that skin-to-skin contact can be introduced into the operating theatre with relative ease, provided adequate training and supervision of staff is carried out. It is also interesting to note that virtually all parents were keen to have skin-to-skin in the operating theatre after reading a simple information leaflet about the study.

Conclusion

For women having an elective caesarean section, skin-to-skin contact (kangaroo care) in the operating theatre, immediately after birth, is associated with a non-significant trend towards an increase in breastfeeding rates at 48 hours, 10 days and 6 weeks. There is a significant correlation between the length of time that skin-to-skin is performed in the first 24 hours by women who have had an elective caesarean section and whether the baby is still receiving breast milk at 48 hours. Further research is recommended.

Skin-to-skin contact between mother and baby can safely and easily be introduced into the operating theatre environment, for women having an elective caesarean section, once staff have received adequate training and there is clear guidance around roles and responsibilities. Close observation of the baby must be performed during this period.

Women enjoy having skin-to-skin with their baby in the operating theatre and appeared to have found the experience beneficial in helping them become a new parent.