An audit was undertaken to explore supervisors of midwives' (SoMs') experience of supervision across a local supervising authority (LSA). Supervision forms part of the professional regulation for midwives, with supervision laid down in statute since the Midwife's Act of 1902 (Jones and Jenkins, 2004; Nursing and Midwifery Council (NMC), 2012). The English National Board for Nursing, Midwifery and Health Visiting (ENB, 1999) defined the role of the SoM as safeguarding the public and enhancing the quality of care for mothers and their families when they use the maternity services. The Nursing and Midwifery Council (NMC, 2004), expanded on this definition, describing SoMs as enabling high quality maternity care through supporting, guiding and empowering midwives, by providing sound professional advice. Above all, SoMs have a regulatory role in protecting the public by promoting best practise, preventing poor practise, and intervening when a midwife's practise falls beneath expectations as written in the Midwives rules and standards (NMC, 2006a).

Midwifery has one of the best systems of professional support and regulation (Warwick, 2009). However, SoMs must make their case locally within their employing organisations as to their effectiveness, in order to justify further funding for the role (Warwick, 2009; Perkins, 2013). They need to respond to a rapidly changing world, with expectations of the SoMs' role continuing to increase (NMC, 2012).

Recruitment of supervisors of midwives

Historically, there have been challenges with recruiting SoMs and retaining them once they are in the role (Kirby, 2013; NMC 2013; Rogers and Yearley 2013). There is evidence of SoMs retiring due to the aging midwifery population, SoMs taking leave of absence from the role or leaving the role completely (Kirby, 2013; NMC 2013). The challenges with recruitment and high attrition rates have made it difficult for employers to achieve the NMC recommended ratio of one SoM to 15 midwives (NMC, 2012; NMC, 2013; Kirby, 2013). The lack of protected time from substantive posts for midwives to undertake the role, affects recruitment and retention of SoMs (Mead and Kirby, 2006; Rogers and Yearley, 2013).

Valuing supervision of midwives

The failure of some employing organisations to value the role of the SoMs results in variations in organisational engagement with supervision, and remuneration for the role (Mead and Kirby, 2006; NMC, 2013; Warwick, 2009). SoMs describe competing demands for their time when discussing challenges of being a SoM, making it difficult for them to commit to the role (Phipps, 2012; NMC, 2013; Rogers and Yearley, 2013).

Mead and Kirby's (2006) evaluation of the time spent by midwives on supervisory activities', is the only research study found in the literature attempting to quantify the amount of time SoMs spend on supervisory activities. They conclude that SoMs need at least 1 day a week, on average, to effectively undertake their role. However, on reviewing the LSA annual report and the NMC report into supervision 7 years on, most SoMs are only getting 7.5 hours a month (1 day), despite the increasing demands on the SoM role (NMC, 2013; Kirby, 2013). Insufficient time allocation results in SoMs performing those tasks that must be done, such as completion of annual reviews, intention to practise (ITP) forms and supervisory investigations, leaving other aspects of the role to reactive supervision. This, in turn, leads to midwives viewing supervision as punitive, because the only time a midwife sees a supervisor is at annual review or when things go wrong (Ralston, 2005; Henshaw et al, 2013; Perkins, 2013).

This audit explored how SoM are managing their role in practice, and the factors that influence this.

Methods

The audit questionnaire was developed using an online survey site. The aim of the audit was to explore SoMs' preparation for their role, once they are appointed, ascertaining whether there is a standardised approach to the amount of protected time that SoMs are allocated throughout the LSA region for their preceptorship period, and SoMs lived experience of their role in practice. Through the audit findings, the author aimed to assess if the majority of SoMs in the LSA are now receiving a structured preceptorship period, as the preparation of SoMs programmes have improved (Dercy and Kirkham, 2006), and the phenomenology of supervision. Due to the wide geographical area in which SoMs work, a link to the audit questionnaire was sent to all SoMs in the local LSA via the LSA Midwifery Officers (LSAMO). There are 193 SoMs working in 17 Trusts, (Kirby, 2013). A covering letter was sent with each audit questionnaire explaining the reasons for the audit and clarifying issues of confidentiality and anonymity for participants. The questionnaire was designed to gather both quantitative and qualitative data for the audit. Winstaneley (2010) discussed the increased validity of using both qualitative and quantitative methods of data collection within a single questionnaire, and the increased knowledge and understanding of SoMs' experiences as a result of using both methods, (Proctor et al, 2010). This article will focus on the quantitative findings of the audit.

The audit examined:

The questions in the audit were benchmarked against the LSA standards for the statutory supervision of midwives, and the NMC rules and standards (LSA, 2005; NMC, 2012).

Audit questions examined how SoMs were fulfilling their role as documented in the LSA standards for the supervision of midwives. SoMs' preparation for their role once they were appointed was questioned, examining whether there is a standardised approach to the amount of protected preceptorship time that SoMs are allocated throughout the LSA. The audit elicited supervisors lived experience of the time allocated for them to undertake their role. SoMs' role as leaders and innovators in midwifery was analysed through seeking information about SoMs' participation in midwives continuing professional development, record-keeping audits and their interface with women requesting care outside guidelines.

Information on the SoMs' substantive role was requested as part of the audit, in order to explore whether the SoM's position within her employing organisation affected her experience of supervision. The audit ended with qualitative questions of factors that SoMs feel empower them in their work, and factors that limit their ability to perform their role as stated in the LSA standards for the supervision of midwives (LSA, 2005). A pilot of the questionnaire was undertaken as no tested tool was available to assess the information required for the audit.

There were 47 responses of the 193 SoMs within the LSA—a response rate of 24.3%. Therefore, the results of the audit are not generalisable due to low response rates. However, the themes identified in the results may support the work that the LSAs are doing to increase recruitment and retention in the SoMs' role.

Ethical approval

Ethical approval for the audit was sought and granted by the University of Hertfordshire Health and Human Sciences ECDA. The LSAMO was informed and permission sought for the audit within the LSA. Permission was granted.

Results

Excel spreadsheets were used to aid calculation of response rates. Each audit response form was anonymous and had a numerical value allocated to it on completion by the survey site. This numerical number was then used to process each respondent's answers. Analysis was undertaken in the order that the audit questions were presented.

SoM preparation for the role following appointment

The first section of the audit explored the length of time SoMs responding to the audit have been in their role, and their socialisation into the role, once they complete the preparation of SoM course (Table 1). The majority of SoMs responding to the audit had been in the role for more than 5 years 57.4% (n=27).

| Length of time as a SOM (years) | Number of SOMs in group (%) | SOMs in each group with preceptor (%) |

|---|---|---|

| >5 | 57.4 | 29.6 |

| 2–5 | 23.4 | 0 |

| 1–2 | 14.9 | 23.4 |

| <I | 4.3 | 100.0 |

Of the SoMs who completed the audit, 70.2% (n=33) had a named preceptor allocated to them by their team when they joined as a newly appointed SoM. The relative increase in the level of preceptorship in the SoM subgroups who have been in the role for less than 2 years may illustrate a change in the support that newly appointed SoMs are receiving and the benefits of preceptorship packages now in use across the LSA (Kirby, 2013). It would be beneficial to target this group of SoMs in a future audit to see if there is real change in the support of newly appointed SoMs as a result of the use of preceptorship packages.

There was a variation in the amount of supernumerary time that newly appointed SoMs had on commencing the role (Table 2)—38.2% of respondents had neither preceptor nor supernumerary time on appointment as a newly qualified SoM.

| Time | No time | 1–3 months | 3–6 months | Unsure |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | 20 | 18 | 4 | 5 |

| % | 42.6 | 38.3 | 8.5 | 10.6 |

Protected time to undertake supervision

The audit explored the SoMs role as leaders in clinical practice, by reviewing the amount of time they were allocated within their employing organisations to undertake supervision. SoMs were asked how much time they were allocated in a 4 week period. The majority, 65.9% (31/47), were allocated 7.5 hours in the 4 week period, with 14.8% (n=7), having 8–15 hours, and 6.8% (n=3), having more than 16 hours designated supervision time. The group with more than 16 hours protected time included a full-time SoM. Two of the SoMs responding to the audit stated that they had less than 7 hours of protected time. Three SoMs, who are in a management role, explained that they had no protected time at all, and undertook supervision around their other work.

Leadership

The leadership role of the SoM was examined using questions that explored specific activities in which SoM would engage with midwives, increasing their visibility in practice. One of these areas was record keeping, because regular audit of midwives records facilitates recognition of poor practise, so that it can be addressed with the midwife (Jones and Edwards, 2003). SoMs were asked about their role in ensuring high standards of record keeping (NMC, 2006b). Of the 47 participants, 23 (48.9%) had participated in a record keeping audit on one to two occasions in their Trust within the preceding year, other than at annual review. Fourteen SoMs (29.7%) had undertaken a record keeping audit on more than five occasions and two SoMs (4.2%) on three to four occasions. Eight SoMs (17%) had never participated in a record keeping audit.

The SoMs role in the organisation and delivery of mandatory update sessions for midwives was explored, with SoMs being asked to elaborate reasons for not participating in this aspect of their role if they had never facilitated these sessions. Overall, 70.2% (33/47), of the SoMs who responded stated that they had participated in the sessions at a frequency ranging from once to more than five times in the preceding year. Fourteen of the SoMs (29.7%) had never participated in any sessions, and the majority of these gave the reason for their non-participation as these sessions were arranged and presented by the practice development midwife.

The SoMs' role in enabling a woman-focused maternity service was briefly explored by requesting information on the number of occasions SoMs supported women requesting care outside their Trust guidelines. Of these, 42.5% (20/47) stated that they did this infrequently (less than once a month), with 36.1% (17/47) of SoMs supporting women at least once a month, and only 10 participants stated that they support women more frequently than once a month.

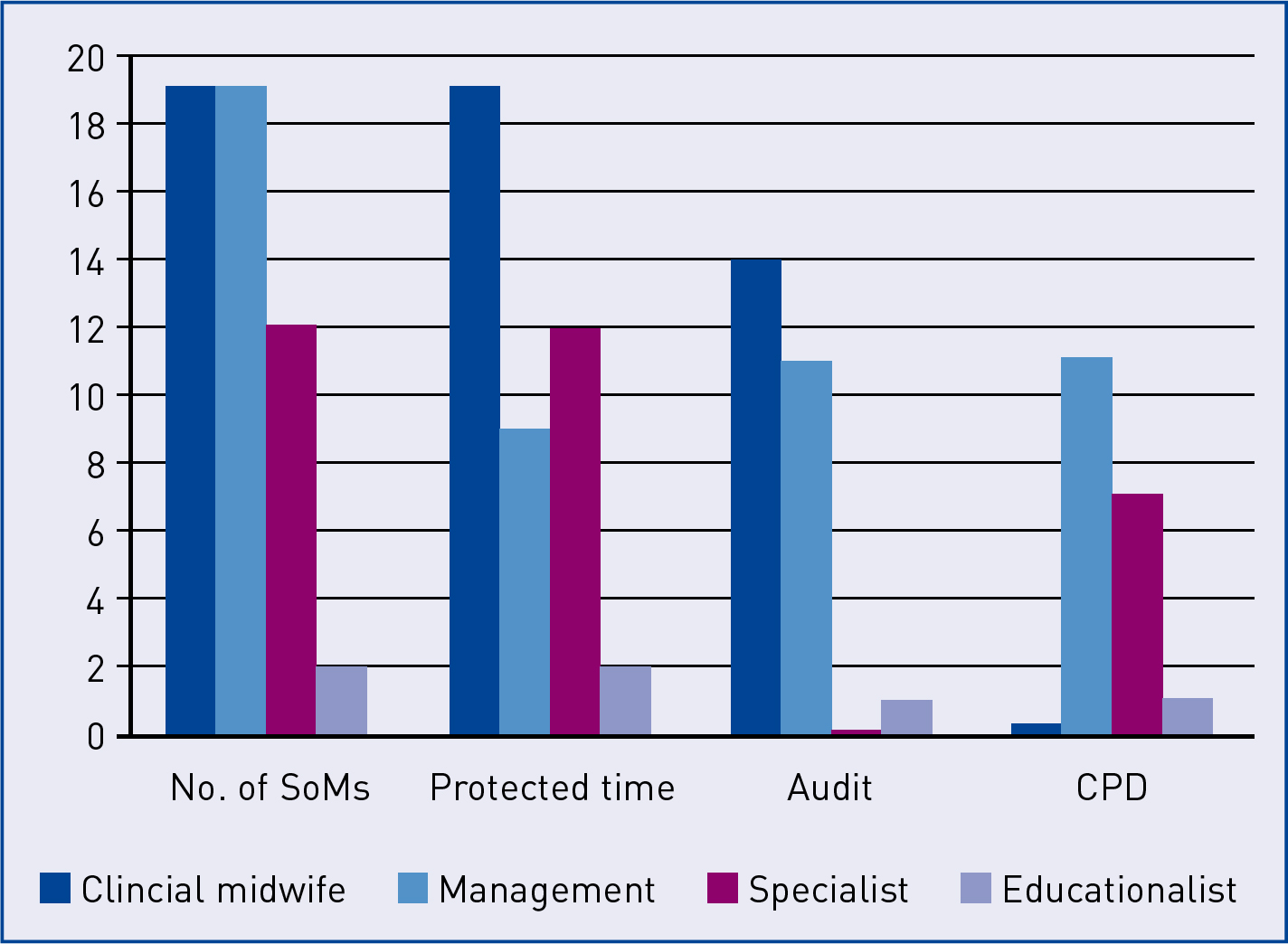

Information on the substantive post of SoMs was included to assess the correlation between the post and SoMs' engagement with the various aspects of the leadership roles that were being audited (Figure 1).

SoMs ability to engage with the areas being audited appears dependant to a certain extent on their substantive role. A larger proportion of SoMs in management roles participated in the record keeping audit and the mandatory updates for midwives compared to their colleagues in clinical roles, despite being less likely to have protected time for the role. This may be due to SoMs in management roles undertaking the record keeping audit and facilitating mandatory updates as part of their substantive role. All SoMs, irrespective of substantive post within the employing organisation, reported supporting women with complicated birth plans.

Discussion

The value of the supervision of midwives is clearly recorded in documentation from the NMC and the literature. There are wide variations in the numbers of SoMs within LSAs and between LSAs, (NMC, 2013; Rogers and Yearley, 2013). The last LSA report has the case load range for the SoMs in the local LSA ranging between 1:12 as a minimum up to 1:23 SoM to midwife ratio. This poses challenges for SoMs in the role which encompasses promoting the safety of mothers and their babies, leading the development of woman-focused maternity services, and ensuring women receive a high standard of care from all practitioners (Warwick, 2009; Rogers and Yearley, 2013).

There is evidence in the literature that SoMs are well-placed to provide leadership within maternity services (NMC, 2006a; Hinchcliffe, 2010; NMC, 2013). Many midwives describe supportive relationships with their SoM, viewing supervision as empowering and developmental, enabling them to provide a high standard of midwifery care, (Stapleton et al, 1998; Henshaw et al, 2013).

The audit explored the phenomenology of supervision within the employing organisations. The audit findings illustrate the challenges that the SoMs have to overcome in order to ensure the provision of a safe, high-quality maternity services, while supporting the midwives who are at the forefront of providing this service (Henshaw et al, 2013). The issues identified relate to preparation for the role as a newly qualified SoM, time to undertake the role, and challenges with undertaking leadership aspects of the role.

Preceptorship

Preceptorship is one of the areas identified, where practice was not within the standards set by the NMC or the LSA, which state that preceptorship for newly appointed SoMs enables them to develop as leaders (LSA, 2005; NMC, 2006a). Preceptorship is an important time following the preparation course for new SoMs to prepare for their role (NMC, 2006a). Of all of the respondents, 29.8% reported not having a preceptorship period as a newly qualified SoM. The NMC (2006a) recommends a preceptorship period of at least 4 months to facilitate the development of newly qualified SoMs into accountable practitioners. Facilitating preceptorship for newly appointed SoMs may strengthen the leadership skills they will have acquired during the preparation course, and increase their understanding of their local SoMs team's strategy for the supervision of midwives. This may help to reduce feelings of vulnerability, which new SoMs may feel during the transition from midwife to SoMs (Stapleton et al, 2000). Conversely, the lack of adequate preparation for the role at the point of appointment may contribute to the attrition rates within supervision. Davis and Mason (2009) observed the importance of preceptorship as a means of preventing attrition from the profession. There are preceptorship packages in use throughout the LSA but there is no uniformity in their use (Kirby, 2013). A standardised preceptorship package given by the LSAMO at the time of appointment may help to overcome this variation in practice, as each newly appointed SoM would then be able to seek out opportunities to facilitate her development in the role.

Supernumerary time

Twenty respondents (42.6%) did not have supernumerary time during their preceptorship period. This raises the question of how they would achieve learning with no protected time within which to do it. According to the local LSA annual report (2012–2013), newly appointed SoMs should be supernumerary for the first 3 months in the role, during which they shadow and are supported by an experienced SoM (Kirby, 2013). However, these findings show that a significant number of respondents did not have supernumerary time when first appointed. This suggests a missed opportunity to facilitate newly appointed SoMs development in their role. Moreover, this is concerning as lack of time to undertake supervisory activities has been noted as a contributing factor to SoMs leaving the role (Kirby, 2013; NMC, 2013; Rogers and Yearley, 2013).

Allocated time for supervision

Time to effectively undertake the supervisory role emerged as one of the main challenges influencing SoMs' experiences in practice, echoing the findings in the literature. Mead and Kirby (2006) concluded that SoMs require at least 7.5 hours a week to effectively undertake their role. However, this recommendation has not been adopted by NHS Trusts across the LSA, despite being based on empirical evidence.

The need for supervision and its functions within the maternity services is clearly written in the NMC documentation and reports (Warwick, 2009; NMC, 2012; NMC, 2013). However as Warwick (2009) explains the challenges lie in the translation of the policy into practice. The NMC (2013) in their annual audit of supervision, found that the lack of dedicated time for supervision despite the guidance that SoMs require protected time to undertake the role has contributed to the resignations and retirement of SoMs. The NMC (2013) reported that SoMs are having to undertake the role in their own time, at times without remuneration. The majority of SoMs responding to the audit were allocated 7.5 hours to undertake their role, within a 4 week period. This finding is consistent with the results of the local LSA audit of supervision, in which the LSAMO noted that time to undertake the role remains problematic (Kirby, 2013). SoMs are expected to use the 7.5 hours a month to perform a multitude of roles. These include, facilitating newly appointed SoMs during their preceptorship, participating in forums to raise the profile of supervision with women using the maternity services, engaging with the Trust executive board in order to be effective leaders of the maternity services, liaising and empowering midwives in clinical practice, as well as undertaking the functions that have to be done as part of the role (Thomas, 2008; Rogers and Yearley, 2013). Perkins (2013) aptly described this cycle of the high expectations from the SoM role and the inadequate time in which to achieve it as, ‘the cycle preventing the promotion of supervision’ (Perkins, 2013: 125). Due to time limitations, SoMs complete those aspects of the role that must be done, reducing their ability to engage in proactive supervision. SoMs participating in the audit described lack of time as challenging, with some of the SoMs noting that they have to fit supervision around their substantive role.

The challenges with time allocation for the role may be due to the variable levels of understanding of the statutory supervision framework and engagement with the supervisory process by the Trusts in which SoMs practise (Henshaw et al, 2013). Henshaw et al (2013) found that NHS Trusts undervalue the role of SoMs within the Trusts' governance process. This is reiterated by the NMC report into supervision (2011–2012), in which the NMC describes differing levels of understanding of the profile of supervision of midwives in Trust boards (NMC, 2013). The NMC (2013) reports that in some NHS Trusts, supervision of midwives has been escalated to executive board level, and is well understood, while other Trust boards have a limited understanding of supervision. This lack of understanding, and valuing of supervision within the Trust hierarchy leads to difficulties with SoMs being allocated inadequate time and remuneration for their role (Warwick, 2009). Perhaps, as Perkins (2013) suggested, SoMs may need to advance supervision by stealth, undertaking the proactive roles of supervision within the limited time allocated, making supervision and its benefits more visible, and through this more resources and time allocation may be allocated to supervision by employing organisations.

Leadership

The challenges with obtaining protected time to undertake supervision impacts on SoMs role as leaders in practice. SoMs need time to develop their leadership potential within the role, in order to drive forward changes within the maternity services. SoMs participating in the audit described the empowering effect of ensuring that women have access to a high quality maternity service.

As illustrated by the different groups participating in the audit, SoMs come from a variety of backgrounds. They all bring different skills and experience to the role and have to work together to provide strong leadership within the organisations they work in (Hinchcliffe, 2010). Leadership development should be encouraged for those SoMs who are not in management roles as a way of promoting the non-hierarchical structure of supervision (NMC, 2011). Some SoMs responding to the audit explained how they felt that their leadership role, as part of the supervisory team, was determined by their substantive role within the organisation. One SoM explained in her audit response how she did not feel valued as a member of the supervisory team because of her substantive post as a band 6 midwife. Another referred to SoMs in management roles within the employing Trust ‘having the final say’, when the SoMs needed to make any decisions as a team.

The struggle between the SoM who is a clinical midwife and the SoM in a management role is examined in the literature. Stapleton et al (2000) described clinically-based SoMs as being viewed by midwives as more trustworthy in terms of support and confidentiality, while SoM who were managers had more organisational power to effect change (Burden and Jones, 1999). This was evident in the findings, with some respondents expressing that SoMs who are managers have the opportunity to attend the different forums and are more visible as SoMs as a result. The challenge for supervision is that if SoMs in management roles engage with the Trust board as individual SoMs in their dual roles rather than a team approach, then the SoM role may merge into the management role (NMC, 2011). In the review into University Hospitals Morecambe Bay, the NMC (2011) found that SoMs were not able to clearly articulate or produce evidence of proactive supervision. Rogers and Yearley (2013) recommend separating the role of manager from midwives roles as SoMs through cross Trust supervision, as this will aid clarity. The NMC (2013) recommended that further work needs to be done to ensure that SoMs are not attending meetings in dual roles. One could argue that while the issue of sufficient protected time for the role has not been addressed the NMC's recommendation will be difficult to achieve with the majority of SoMs having 7.5 hours of protected time in which to undertake all their role requirements. Clinically based SoMs struggle to prioritise supervision with the increasing service needs making it difficult for them to leave clinical areas (Kirby, 2013).

SoMs in this study identified specific leadership activities they participate in their employing organisations. These include supporting and enabling midwives in their continuing professional development, participating in record keeping audits and, supporting women who use the maternity services. The findings demonstrated that SoMs in management, as a group, had more involvement with audit and midwives continuing professional development compared to their colleagues in clinical practice. The NMC (2013) report into supervision, support and safety of the quality assurance of LSA (2011–2012) found that there was no significant increase in the number of women accessing supervisors of midwives directly. The majority of SoMs in this study did engage with women with complicated birth plans, but these are only a small number of women who use the maternity services. SoMs need to consider ways of raising the profile of supervision with women.

Conclusion

The audit findings illustrated that despite the challenges of the role, SoM are working towards the standards of their role as written by the NMC in the Standards for the preparation and practise of supervision of midwives, and the LSA standards for the statutory supervision of midwives. There needs to be an improvement in how SoMs facilitate newly-appointed SoMs' socialisation into the role, with improved use of preceptorship, and supernumerary time. Adequate protected time is required if SoMs are to reach their potential as leaders in clinical practice. Supervision needs to continue evolving and SoMs should become proactive in taking the midwifery profession forward while ensuring that women have access to a service of the highest standards (Perkins, 2013). Employing organisations need to demonstrate their valuing of supervision by facilitating SoMs to have enough time to effectively perform their role.