References

Reflecting on why surgical swabs are being left behind and exploring how this could be prevented

Abstract

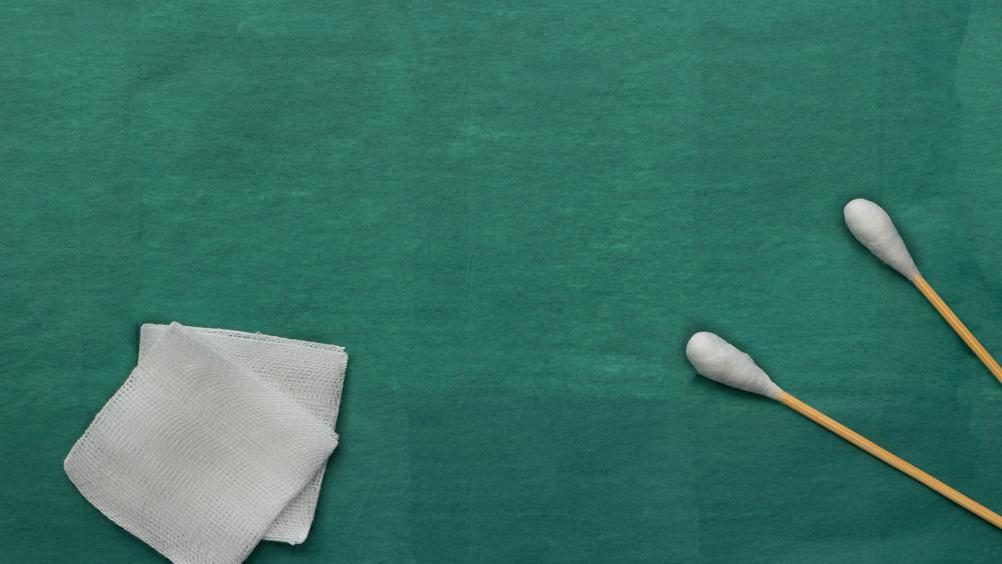

Surgical swabs are routinely used by obstetricians and midwives to absorb blood during caesarean sections or perineal repairs following a vaginal birth. On rare occasions, a surgical swab can be left behind by mistake inside the patient's body. When an incident involving a retained swab occurs, this is declared a ‘never event’. Although a rare occurrence, a retained surgical swab is the source of high morbidity (infection, pain, secondary postpartum haemorrhage and psychological harm). It is also important to mention the financial burden and the legal implications affecting healthcare providers worldwide. Over the years, several strategies have been implemented in clinical practice to reduce such risk. However, none of these seem to provide a definitive answer. Having offered a brief overview of the evidence surrounding retained surgical swabs, this article presents an innovative approach based on creating a physical barrier by introducing an anchoring point linking the swabs together, making it physically impossible to leave one behind. At present, these modified swabs are undergoing development and testing.

As the name suggests, a ‘never event’ should never happen in the first place. Never. Unfortunately, this is not the case. Incidents involving surgical swabs being left behind, particularly during a caesarean section or a perineal repair following a vaginal birth, are still happening despite over 100 years of institutional awareness of the problem and tentative solutions being implemented in clinical practice. This article focuses on a UK perspective, with the acknowledgment that never-event incidents involving retained surgical swabs are a widespread problem affecting healthcare systems worldwide. It is therefore reasonable to ask the question: why are surgical swabs being left behind and what can be done to prevent this from happening?

In medical literature, retained surgical swabs are referred to as ‘gossypiboma’ (Williams et al, 1978; Zbar et al, 1998; Kiernan et al, 2008). The etymology for gossypiboma appears to derive from ‘gossypium’ (Latin for ‘cotton’) and the suffix ‘oma’ (Latin meaning ‘mass’). It was first described and reported in the literature back in 1884 (Wilson, 1884), well over a hundred years ago. More recently, it is not uncommon to find the term ‘textiloma’ instead, due to the increasing use of synthetic materials to replace cotton. All surgical swabs used in the UK contain radiopaque threads that theoretically allow swabs to be detected by X-ray and CT scans. Despite this, diagnosis is often challenging as clinical presentation varies significantly. Often, patients present with vague clinical symptoms over a significant period of time. The most common symptoms are discomfort, pain, unexplained fever or feeling generally unwell. In some cases, the patient is asymptomatic and the retained surgical swab is only diagnosed incidentally. Moreover, diagnosis can occur days, weeks, months or ever years after the surgical event, increasing the likelihood of severe morbidity associated with the retained surgical swab.

Register now to continue reading

Thank you for visiting British Journal of Midwifery and reading some of our peer-reviewed resources for midwives. To read more, please register today. You’ll enjoy the following great benefits:

What's included

-

Limited access to our clinical or professional articles

-

New content and clinical newsletter updates each month