In March 2020, the first of a series of national lockdowns was implemented in Ireland as a means of reducing the community spread of COVID-19. This resulted in changes to maternity care practices that had the potential to impact the clinical and experiential outcomes of women accessing maternity care during this time (Coxon et al, 2020). Some of the implemented changes included restrictive visiting policies, such as having one designated parent for babies in the neonatal intensive care unit, no visiting on antenatal, postnatal and gynaecology wards, reconfiguration of physical space to accommodate suspected or confirmed cases of women with COVID-19, suspension of key services such as parent education, antenatal classes and birth reflection clinics, increased antenatal and postnatal telephone consultations and displacement of some outreach antenatal clinics back to the hospital. Many of these changes, while described in the Irish context, are not isolated to maternity care in Ireland, rather they reflect changes that occurred internationally (Menendez et al, 2020; Renfrew et al, 2020; Roberton et al, 2020; Jardine et al, 2021). For example, in the UK, around one-third of NHS Trusts suspended the provision of home birth services, affecting place of birth choices for many women (Sherwood, 2020). Over a year later, many of these changes remain in place in Ireland, and are increasingly receiving media attention, especially policies that restrict partner visiting and the effect this is having on women's wellbeing (Power and O'Halloran, 2021).

Although the risk of contracting COVID-19 does not appear heightened by pregnancy, nor are pregnant women more likely, it appears, to die from the disease, emerging evidence suggests that morbidity in pregnancy is higher with COVID-19. In a living systematic review (March 2021 update) involving 192 studies, Allotey et al (2021) showed that the need for admission to the intensive care unit and the need for invasive ventilation were respectively 2.1 and 2.6 times higher for pregnant women with COVID-19 when compared to non-pregnant women of reproductive age. In cohorts of pregnant women who were positive for COVID-19, compared with pregnant women who were negative, the chance of maternal death, admission to the intensive care unit, and preterm birth were all higher (Allotey et al, 2021). More concerningly, recent media reports have linked stillbirth to COVID-19 as a result of COVID-19 placentitis (Cullen, 2021). Reports have also indicated increased rates of caesarean section and other clinical outcomes as a result of the pandemic (Della Gatta et al, 2020; Lian et al, 2020), with a woman's COVID-19 status being an apparent determining factor in some cases. For example, pooled prevalence rates of caesarean section in women positive for COVID-19 were reported as 78% and 88% in two systematic reviews (Capobianco et al, 2020; Juan et al, 2020), and a recent study from India involving just over 3000 women reported a caesarean section rate of 58.3% in pregnant women positive for COVID-19 compared to 29.8% in women who tested negative (Gupta et al, 2021).

By adding to the current body of evidence, the authors aimed to explore the impact of COVID-19 on maternity care in Ireland through a two-phase study that evaluated both clinical and experiential outcomes in women. Phase 1 involved a comparative review of maternal clinical outcomes before and during the COVID-19 pandemic. Phase 2 involved interviews with 19 women to gain an understanding of their experiences of maternity care during the pandemic (Panda et al, 2021). In this article, the key findings from Phase 1 are outlined.

The aim of the study was to compare pregnant women's clinical outcomes for 4 months before and 4 months during the implementation of maternity care practice changes resulting from the COVID-19 pandemic at a hospital site in Ireland.

Methods

A before and during comparative study of maternal pregnancy, labour and birth, and postpartum clinical outcomes was conducted at an urban-based tertiary maternity hospital in Ireland with an annual birth rate of approximately 8000 births.

Data collection and analysis

Information on women's clinical outcomes (eg labour induction, mode of birth, initiation of breastfeeding, length of postnatal stay, admission to the neonatal intensive care unit and readmission rates), recorded as part of routine hospital care, were extracted from the hospital electronic information system by a gatekeeper who worked in the information technology department of the hospital and who had no other involvement in the study. Data were collected in August 2020 and provided to the research team in aggregated, anonymised format; that is totals of the clinical outcomes of interest to the study. The first set of data were from mid-December 2019 to mid-March 2020 (the before COVID-19 cohort) and the second were from mid-March to mid-July 2020 (the during COVID-19 cohort). A priori sample size estimate was not necessary for the study, rather the sample size was based on all those who had given birth at the hospital during the study period.

Data were comparatively analysed and reported as frequencies and proportions. Inferential statistics, which included Z-test scores, odds ratios and 95% confidence intervals were used to compare the before and during data, with significance set at P<0.05.

Ethical considerations

Ethical approval was granted by the lead researcher's University Research Ethics Committee (Chair_1_20.21) and by the study site's Research Ethics Committee (Study No.16 2020). A requirement for individual participant written informed consent was waived for the comparison of clinical outcome data as these data were extracted and presented in an aggregated format based on routinely collected clinical data from the hospital's electronic information system. On booking for their maternity care at the hospital, women are informed that aggregated, anonymised clinical outcome data may be used in this way, so as to support practice improvement and innovation in practice, and to assist the hospital overall in striving towards optimal maternity care.

Results

Data on 4886 women who gave birth at the study site during the study periods were analysed; 2441 women in the pre-pandemic period and 2445 women in the during-pandemic period. Table 1 presents a summary of the monthly and total numbers included, overall and by parity.

Table 1. Summary details of numbers included in the study

| Women who gave birth, n=4886 (%) | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Before COVID-19 group (16 Nov 2019–15 March 2020) | During COVID-19 group (16 March 2020–15 July 2020) | |||||||||

| Month 1 | Month 2 | Month 3 | Month 4 | Total | Month 1 | Month 2 | Month 3 | Month 4 | Total | |

| Primiparous | 277 | 270 | 288 | 249 | 1084 | 248 | 236 | 235 | 247 | 966 |

| Multiparous | 333 | 363 | 346 | 315 | 1357 | 321 | 375 | 389 | 394 | 1479 |

| Total | 610 | 633 | 634 | 564 | 2441 | 569 | 611 | 624 | 641 | 2445 |

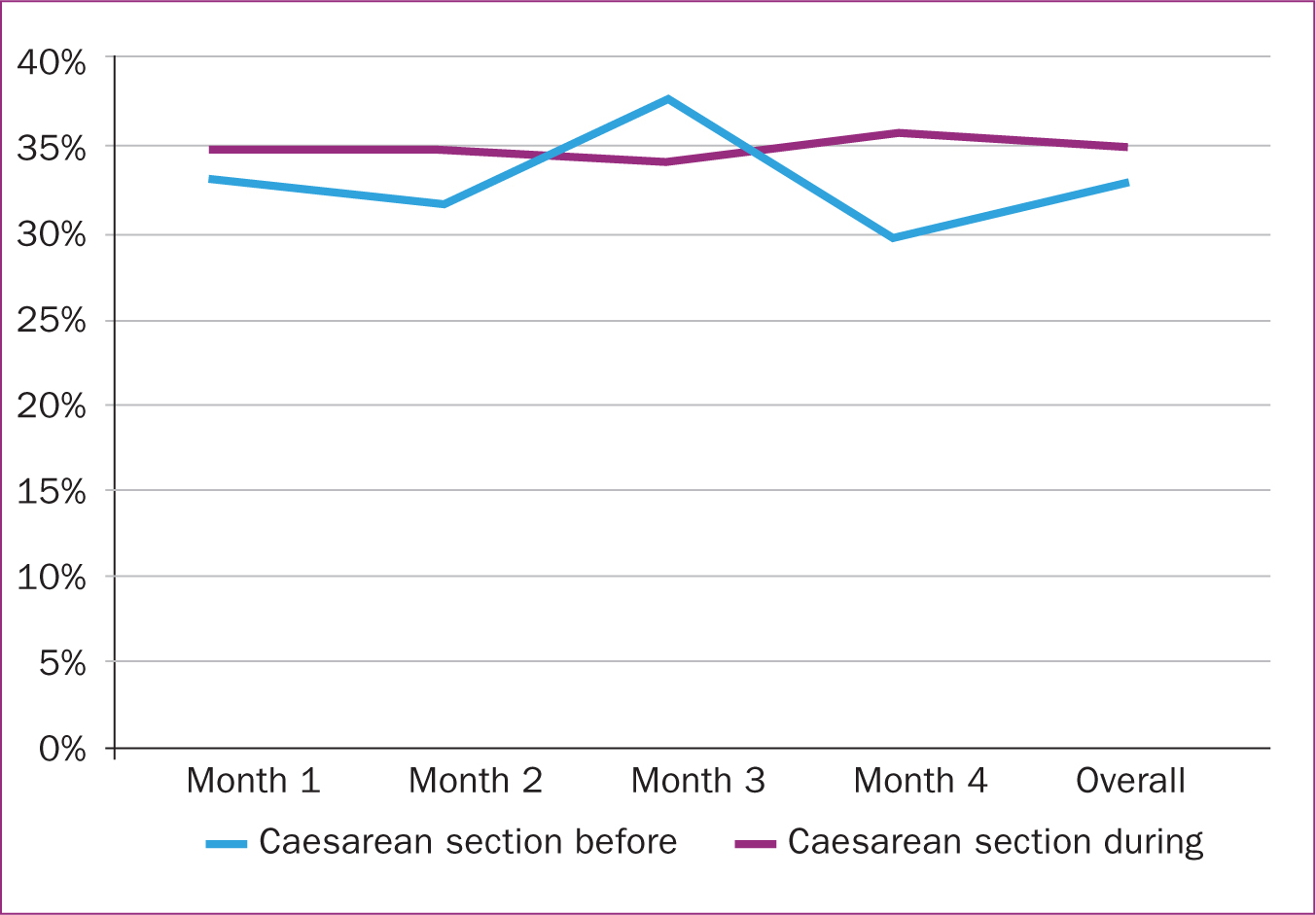

Overall, the rate of caesarean section remained unchanged across the before and during study periods (33% vs 35%, P=0.22). Pre-pandemic monthly variable fluctuations in caesarean section rates were evident, from 29.8% to 37.7%; however, this variability appeared reduced during the pandemic, with monthly caesarean section rates remaining relatively stable each month, ranging from 34.3% to 35.7% (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Caesarean birth overall

Figure 1. Caesarean birth overall

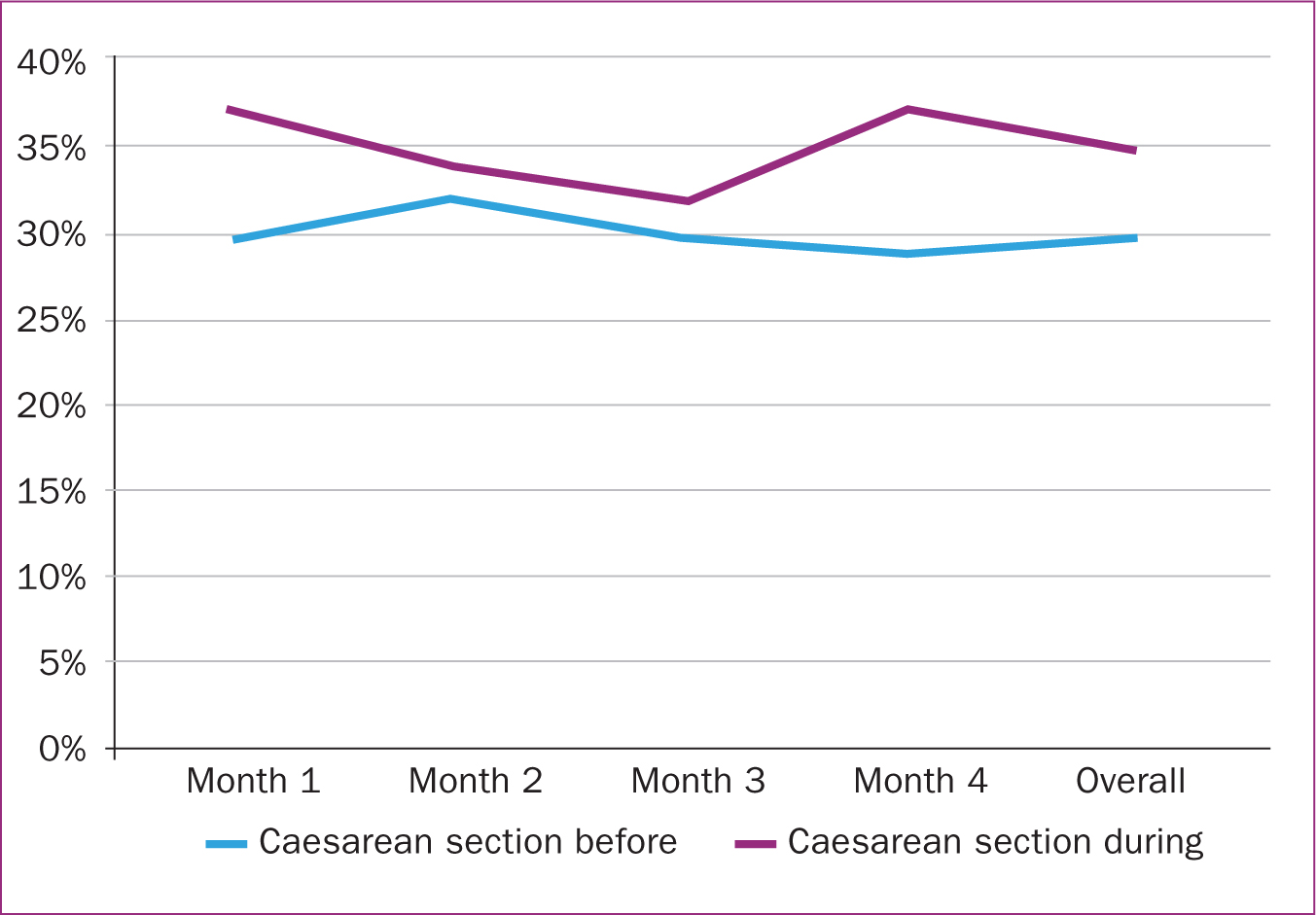

When caesarean section rates were analysed separately by parity, an increase was observed in multiparous women during the pandemic compared to pre-pandemic (30% vs 35%, P=0.01) (Figure 2). Caesarean section in primiparous women was decreased from 37% to 35%, though the difference was not significant (P=0.4).

Figure 2. Caesarean birth in multiparous women

Figure 2. Caesarean birth in multiparous women

Comparing elective (planned) and emergency caesarean section as part of overall rates from before and during the pandemic revealed an increased elective rate during the pandemic. This split had been relatively balanced before the onset of COVID-19 (Table 2).

Table 2. Elective vs emergency caesarean section

| Elective vs emergency caesarean section | Difference | |

|---|---|---|

| Before (n= 813) | 48.2% (n=392) vs 51.8% (n=421) | 3.6% (P=0.27) |

| During (n=855) | 56.8% (n=486) vs 43.2% (n=369) | 13.6% (P<0.0001) |

Concomitant changes in spontaneous vaginal birth and assisted vaginal birth were also observed between the two time periods, but these changes were not significantly different (spontaneous: 56% vs 52%, P=0.15; assisted: 12% vs 13%, P=0.3).

Other intrapartum outcomes

Although induction of labour overall remained relatively stable across the two time periods, post-maturity induction of labour, defined as ≥term +10 days, was significantly higher in the during period compared to the pre-pandemic period (Table 3). A significant increase in augmentation of labour following spontaneous onset of labour in the immediate-term following COVID-19 (month 1) was also observed, but this difference balanced out over the two 4-month study periods, and a significant difference overall was not observed (Table 3).

Table 3. Other intrapartum outcomes

| Variable | % before | % during | Odds ratio (95% confidence interval) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overall induction of labour | 37.6 | 36.9 | 1.03 (0.91–1.15) | 0.65 |

| Induction month 1 | 38.5 | 35.1 | 1.15 (0.91–1.47) | 0.25 |

| Induction post-maturity | 12.4 | 16.7 | 0.70 (0.54–0.91) | 0.007 |

| Augmentation of labour after spontaneous onset | 18.4 | 20.1 | 0.90 (0.72–1.13) | 0.38 |

| Augmentation month 1 | 18.0 | 27.5 | 0.58 (0.36–0.92) | 0.02 |

| Epidural analgesia | 41.6 | 40.1 | 1.06 (0.9–1.19) | 0.29 |

Postnatal outcomes

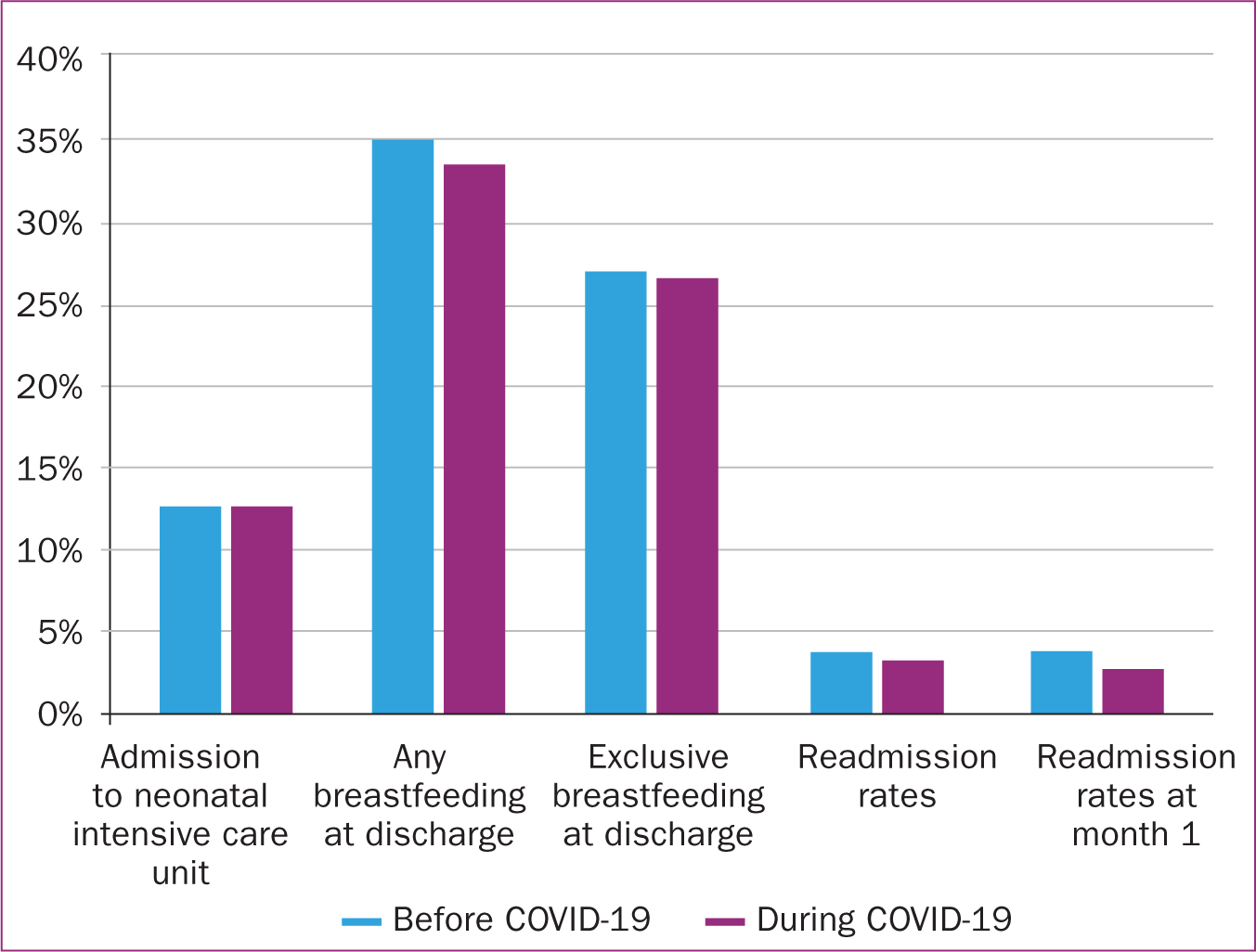

Figure 3 presents the results for some key postnatal outcomes. No differences were observed in the outcomes of admission to the neonatal intensive care unit (12.3% vs 12.4%), breastfeeding at discharge (any: 34.8% vs 33.2% or exclusive: 26.8% vs 26.5%) and postpartum readmission rates (3.7% vs 3.2%).

figure 3. Postnatal outcomes

figure 3. Postnatal outcomes

Discussion

In general, practice changes implemented in response to the COVID-19 pandemic at the study site have affected relatively few maternal clinical outcomes, although those that appear to have been affected have the potential to impact considerably on women's intrapartum and postpartum health and wellbeing. Such outcomes included proportionally increased elective compared to emergency caesarean section rates, increased caesarean section in multiparous women, increased augmentation of labour and increased rates of induction of labour for post-dates (post maturity induction). Further exploration is warranted to explain these findings, but practices related to controlling the environment following lockdown may have been influential drivers. For example, the increased elective caesarean section rate compared to emergency and the increase in caesarean section in multiparous women may be interlinked. As a result of the pandemic, women with previous caesarean sections may have been more inclined, or may have been advised to opt for an elective repeat caesarean section, rather than plan for a vaginal birth after caesarean section. This might be because the former allows for scheduling and thus a degree of control over maternity admissions and reduces the potential for random or fragmented maternity admissions during the lockdown period.

The present findings are largely based on women who were known or suspected to be COVID-19 negative, as the known COVID-19 positive rate for women attending the study site during the early stages of the pandemic was <1%. This rate is considerably less than the 10% known incidence of COVID-19 in the pregnant population globally (World Health Organization Collaborating Centre for Global Women's Health, 2020). Research has shown that being positive for COVID-19 impacts on caesarean section rates, ranging from 65–100% across studies, depending on the severity of the disease (Gao et al, 2020; Martinez-Perez et al, 2020). The overall caesarean section rate at the study site was high compared to the 10-15% rate beyond which the World Health Organization (2015) has noted there is no associated reduced maternal or neonatal mortality. However, reassuringly, the rate remained unchanged, although the increases in caesarean section in multiparous women is concerning and warrants exploration. An interesting and unexpected finding was an increased rate of post-maturity induction of labour (defined as >term+10 days at the study site) during the COVID-19 pandemic period compared to the pre-pandemic period. Reassuringly, no apparent maternal or neonatal adverse consequences were concomitantly observed. Although the exact reasons for this observation are unknown, one possible reason could relate to minimising attendance at the hospital until necessary, from both women's and healthcare providers' perspectives. This resonates with other study findings; for example, a UK survey found some changes to induction of labour practices took place since the onset of COVID-19, including more women returning home during cervical ripening, which may be linked to minimising hospital admissions and restrictions on partner attendance (Harkness et al, 2021). Qualitative data reporting on women's experiences of maternity care during the COVID-19 pandemic have repeatedly identified issues of sadness, loneliness and anxiety experienced by women as a result of partner restrictions (Cullen et al, 2021; Panda et al, 2021) and is likely to be a major influencing factor on induction of labour rates. Breastfeeding rates remained unchanged at the study site during the COVID-19 period. Although breastfeeding rates in Ireland have been historically low, women have reported that the peace and quiet of the postnatal wards afforded by prohibited large-scale visiting during the pandemic offered them a comfortable environment in which to establish breastfeeding practices (Panda et al, 2021). Consequently, it might have been hoped that overall breastfeeding rates would have increased, but this was not borne out in the data.

Limitations

Although the present study is based on an analysis of clinical outcome data from large numbers of women, the data are limited in that only aggregated data were used, and thus an exploration of possible confounding on outcomes was not possible. In addition, the study relates to pregnancy and childbirth outcomes during the early stages of the pandemic, when anxiety and fear of the unknown were highly prevalent. It is possible that as the pandemic continued and further evidence became available, further differences might be observed, or those observed in the present study may no longer exist. Finally, the study was conducted at a large maternity site in Ireland. Although the practice changes implemented at the site are reflective of those implemented national and internationally, the authors acknowledge that individual variations in practices across units exist. As such, these findings might not necessarily be generalisable to different settings and environments.

Conclusions

This study has highlighted an apparent impact of COVID-19 on maternal pregnancy and childbirth outcomes. Having an awareness of these findings is helpful throughout the COVID-19 pandemic and beyond it. The findings offer insight and will be informative for maternity care providers in assessing possible effects on women's labour, birth and postpartum outcomes, and whether the consequential impacts have the potential to affect women's overall health and wellbeing positively or adversely, both in the short- and longer terms. This will assist in future care planning for women who have and who are accessing the maternity services throughout the pandemic and beyond.

Key points

- COVID-19 has resulted in considerable changes to maternity care practices that may impact on women's clinical and experiential outcomes

- Some changes to birth outcomes were observed early in the pandemic in one large maternity setting in Ireland

- These changes included proportionally increased elective compared to emergency caesarean section, increased caesarean section in multiparous women, increased augmentation of labour and increased rates of induction of labour for post maturity

- Having awareness of the impact of COVID-19 of pregnancy and childbirth outcomes is helpful when considering women's overall health and wellbeing, in the short- and longer term

CPD reflective questions

- Rising caesarean section rates are a global concern; how might multiparous women have been better supported towards natural childbirth during the pandemic?

- What impacts might the observed changes to labour and birth outcomes have on women's longer-term health and wellbeing?

- Although the pandemic has endured, we are hopefully moving towards a post-pandemic phase. What lessons can we take from the pandemic to help us provide high quality, safe maternity care into the future?